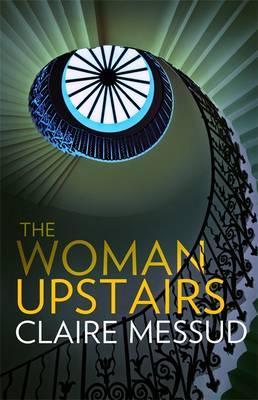

| When Fleur Smithwick, one of the early endorsers of my debut novel, Sugar and Snails, likened my central character, Diana, to the narrator of The Woman Upstairs, I was flattered. I knew that the author, Claire Messud, was well regarded by the literati and, although I hadn’t read it, the reviews suggested The Woman Upstairs was my kind of book. I also recalled some fireworks around the publicity, when (presumably male) reviewers and interviewers had queried the creation of an angry female character. Having finally read the novel, I followed this up to discover an article in the New Yorker on character likeability. Interesting as that article is, I’m shocked that it stems from an unchallenged assumption that readers will agree that Nora is unlikeable, not someone you’d want as a friend. |

Like her almost-namesake, Norah Colvin, she’s an extremely empathic early-years teacher, as well as a loyal friend. She’s not entirely to blame for taking her friendship with all three members of the Shahid family too far; for each of them, she’s an all too convenient stopgap for the relationships they’re missing during their year’s sabbatical in the USA.

Given her reputation as unlikeable, I was expecting Nora to behave like Barbara in Notes on a Scandal (incidentally, another single schoolteacher), using her inside knowledge to control her friend. But on the contrary, it’s Nora who’s betrayed, certainly by Sirena, and quite possible by Sirena’s husband, Skandar, too. Perhaps she’s as romantically naive as twelve-year-old Frankie in The Member of the Wedding in her wish to be part of something that isn’t hers. But she’s not stupid. Despite her fantasies of happy ever afters, all she wants is for the friendship she’s apparently offered to be genuinely meant.

As well as being a decent human being, there’s a lesson in Nora for all of us in how to live. If we don’t want to end up fuming at life’s disappointments, perhaps we need to put limits on how much we’re prepared to forego our own ambitions in order to serve the needs of others. Compassion for ourselves should come first. And if we have a friend who seems all too willing to compromise in our favour, perhaps, if we don’t want to lose them, we need to be careful not to take advantage of their good nature. Perhaps too, without giving away the ending, we could use Nora as a role model, and become motivated by our anger. Maybe that’s what the male critics didn’t like.

In contrast to Nora, my character Diana’s anger in Sugar and Snails is pretty tame. Apart from a couple of fucks, this is probably as good – or bad, depending on your position on anger – as it gets (p123-4):

I needed a door to slam behind me, but the one to my office had a top closer that eased it sedately into the frame. I needed hail pelting the window, but sun streamed through the glass, the deluge abated. I needed to kick my bike over, but the space between the bookshelf and easy chairs was so narrow, the saddle was caught by the chairback and all I got was an aching toe.

Interestingly, I hadn’t read this book when Caroline Lodge post me some questions for a blog post on Is There Discrimination against Older Women Writers? I felt I’d let her down in a way as, while I’m sure we must be subject to ageism and sexism in publishing as in other areas of life, I wasn’t conscious of having received any. But I had wondered if there’d been discrimination against my character, a mere toddler at forty five. If so, then with Nora, Diana’s in good company.

Have you ever found yourself liking fictional characters everyone else considers unlikeable? Do we, women as well as men, unrealistic standards for female friendship? What’s wrong with an angry woman?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed