Enduring love. Loss. The eternal struggle for life’s meaning. The hand that first held mine. Atonement. Yes, there are book titles mixed up in there, but these are also the themes of my writing.

My influences probably started with Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, maybe that’s the first memory I have of a deep feeling of poignancy: an understanding of irretrievable loss. Peter wants to fly free for a while, as all babies (according to J.M. Barrie) are capable of, but he leaves it too late to return to his mother. The window is barred and she has another baby; there is no place now for him. He spends his life as an eternal boy, living in Neverland, regretting his loss of ‘Mother’.

A book that impacted deeply on me as an older child was A Dream in The House. Every generation of a family has a set of twins named Ann and Jane, and the Ann always disappears and the Jane tries to get her back. Once the final Jane manages to retrieve her twin, every other Ann is also restored in retrospect. Loss of ‘Self’, perhaps, in the symbolisation of the twin.

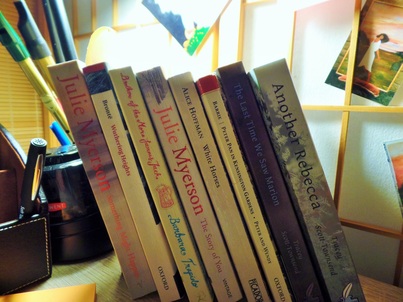

I discovered Alice Hoffman when I was twenty-one. The first novel of hers that I read was White Horses. The main character, Teresa, suffers from sleeping sickness, and she is abnormally close to her brother, the enigmatic Silver. Therein lie the inspirations to my characters Cal and Marion in The Last Time We Saw Marion. Cal is dark and unpredictable, like Silver, and Marion/Marianne suffers from catatonic episodes similar to Teresa’s sudden bouts of overpowering sleep. Alice Hoffman’s writing helped develop my own eventual writing style as well, or was at least a strong influence in how I wanted my sentences to seamlessly incorporate the everyday and the slightly magical. I don’t want everything to be explainable. I want lyricism but with a biting edge, love with its accompanying possibility of loss. Light and dark, contrast is everything. A review of my recent novel Another Rebecca (Inspired Quill 2015) states: “Tracey… describes unearthly events – fleeting glimpses of something the reader cannot see, whispers we cannot fully hear, a brush of something not quite real against our skin – yet at the same time, she pulls no punches in her earthy descriptions of the all-too-human protagonists.” (Sharon Booth, Goodreads review, Another Rebecca)

In my mid-twenties I came upon Brother of the More Famous Jack by Barbara Trapido. The book is Trapido’s first novel. Katherine is fresh from her suburban upbringing when she becomes involved with the family of Jacob Goldman, her Jewish philosophy lecturer. Katherine hankers after his son Roger, whilst Jonathan is always there in the background. I identified particularly strongly with this novel on first reading because Katherine suffers the loss of a baby, as I had done. The part that brought me to tears was: “My baby had some mob caps. She hadn’t grown into them, of course. I mean, she couldn’t even hold her head up, Jonathan.” It taught me to write only a few words, but to make them effective. Too much description would have diluted the power of the grief. I tried to reflect this principle in my telling of the death of baby Caitlin in The Last Time We Saw Marion.

Julie Myerson novels were recommended to me by a librarian in the early 2000’s. I first read Laura Blundy, followed by Me and the Fat Man. I’d discovered a writer who delved into the deepest depths of human nature. Myerson’s novels are transgressive, there is always motherhood and often sex involving mothers who are heavily pregnant or have recently given birth. There is loss and heartache, love and other-worldliness. The narratives are stark and simple, the prose compelling. Of all her novels, my writing has been most influenced by The Story of You. Bex and Rebecca in Another Rebecca conjure up Sebastian out of sheer need and willpower, similarly to Nicole conjuring her former lover and her baby in The Story of You.

Audrey Niffenegger is the final influence I’m going to cite, although there are many more. Niffenegger threads the supernatural throughout her complex, multi-layered narratives, in The Time Traveller’s Wife and Her Fearful Symmetry. In both novels Niffenegger persuades the reader to suspend belief with the authority of her narrative.

Thank you Tracey for this inspiring post.

Follow the embedded links for more on Tracey’s two published novels, or connect with her here:

Website http://traceyscotttownsend.com/

Facebook Author page https://www.facebook.com/AuthorTrace

Twitter @authortrace https://twitter.com/authortrace

RSS Feed

RSS Feed