Two women’s lives are shattered by the sudden death of a fourteen-year-old boy. Hannah, an idealistic drama teacher, tries to heal herself battling the extremes of winter chills and summer heat on a smallholding in rural Bulgaria. When she welcomes the older woman into her home as a volunteer, she is unaware that the quiet psychiatrist is the mother of the awkward boy who she tried and failed to protect from a coterie of bullies. But the reader knows, as we’ve been following Kito’s mother’s story since the beginning, from when she and her husband, Mark, adopted a baby from abroad, to the day he failed to return from school, to the year he should have turned eighteen when she sets out to extract revenge from the woman she believes is responsible for his death.

I loved the voice of Kito’s mother. I loved that, like Kevin’s mother in Lionel Shriver’s acclaimed novel, she’s highly ambivalent about mothering and doesn’t do it very well. I loved how the two women both echo and contrast each other’s qualities. For example they’re polar opposites in terms of their belief in their own power to help: while, despite her inability to command basic discipline, Hannah is overconfident that Shakespeare can civilise a bunch of adolescents and rescue the class scapegoat from both the mob and his own inhibitions, his mother has adopted a noninterventionist strategy (except when she clumsily doesn’t, insisting he has a birthday party to which no-one comes), hoping he’ll be fortified by finding his own solutions.

Kito’s mother is similarly low-key in her attitude to her work as a psychiatrist who practices therapy. (I couldn’t decipher what kind, but it was mentioned enough to earn her the accolade of fictional psychotherapist – the twenty-eighth in my series.) She works in mental health because she wasn’t quite good enough to get a job in a more prestigious specialty, just as Hannah drifted into teaching because her acting skills weren’t up to scratch. Even so, I couldn’t quite make up my mind if she was appropriately realistic or inappropriately disengaged (p64):

I was good at my job, but I wasn’t the understanding friend my patients liked to see in me. Their weakness often repulsed me. Their inability to keep their emotions in check and their capacity to abandon themselves to their grief struck me as a lack of character. I didn’t understand how they could let themselves go like that.

Translated from the Dutch by Sarah Welling, and published by Hope Road (who provided my review copy), The Boy is a beautifully written and poignant novel about adoption, motherhood, racism, adolescence, and the perils of misplaced heroics within helping relationships. For another novel on bullying, see Bone by Bone by Sanjida Kay, who just happens to have written a novel about adoption too.

Seven years on, the family has relocated to Yorkshire, with a surprise addition in two-year-old Ben, conceived naturally against the odds. Ollie’s pressured job as an accountant has bought them a comfortable house with a view of the moors, which inspire Zoe’s work as a visual artist. Life is good, despite the tensions, as Zoe resents Ollie’s long hours at work leaving her to juggle the demands of two young children with her creative ambition. It’s also unclear how much Evie has been damaged by her birth mother’s drugs. With her darker skin and elfin features, she is increasingly curious about her origins, and jealous of the attention her little brother receives.

Zoe feels similarly deprived of attention, such that when she meets Harris, another artist who seems to intuitively understand her, she doesn’t hesitate to make time in her busy schedule to meet up with him for coffee, walks on the moor and the possibility of more. So she’s a little distracted when she discovers that Evie has hidden letters and gifts from someone who claims to be her real daddy, communications that make her feel special and loved.

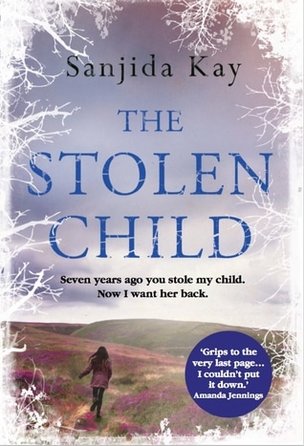

So the pins are lined up for a real page turner when Evie disappears. Who has abducted her and will she be found before any damage is done? The finger of suspicion gravitates from one character to another (without the overloading of possibilities that can, in less skilled hands, make this reader lose track), with Zoe’s – and the reader’s – assumptions challenged by the options overlooked. I’m impressed how the author has engineered this narrative tension without compromising on character depth. You don’t need to be a parent to be moved by the narrator’s guilt and fear. It’s also a convincing portrait of how ordinary life does and doesn’t carry on at the heart of any kind of crisis, with a toddler and a dog still needed to be fed and entertained, and how their separate griefs widens the gap between husband and wife.

With a complimentary copy from the publisher, Corvus, and a generous endorsement from the author of my own forthcoming psychological suspense novel, I was primed to like this book. But it’s no exaggeration to say that Sanjida Kay has nailed the literary thriller genre with The Stolen Child. It succeeds as both a twisty-turny thriller and psychologically astute examination of a family under extreme stress. There was an added bonus for me in the setting on the edge of Ilkley Moor, where I’ve had some wonderful walks. If you like fiction that adds an extra layer of tension, or two, to the challenges of mothering, you might also enjoy her first published thriller, Bone by Bone.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed