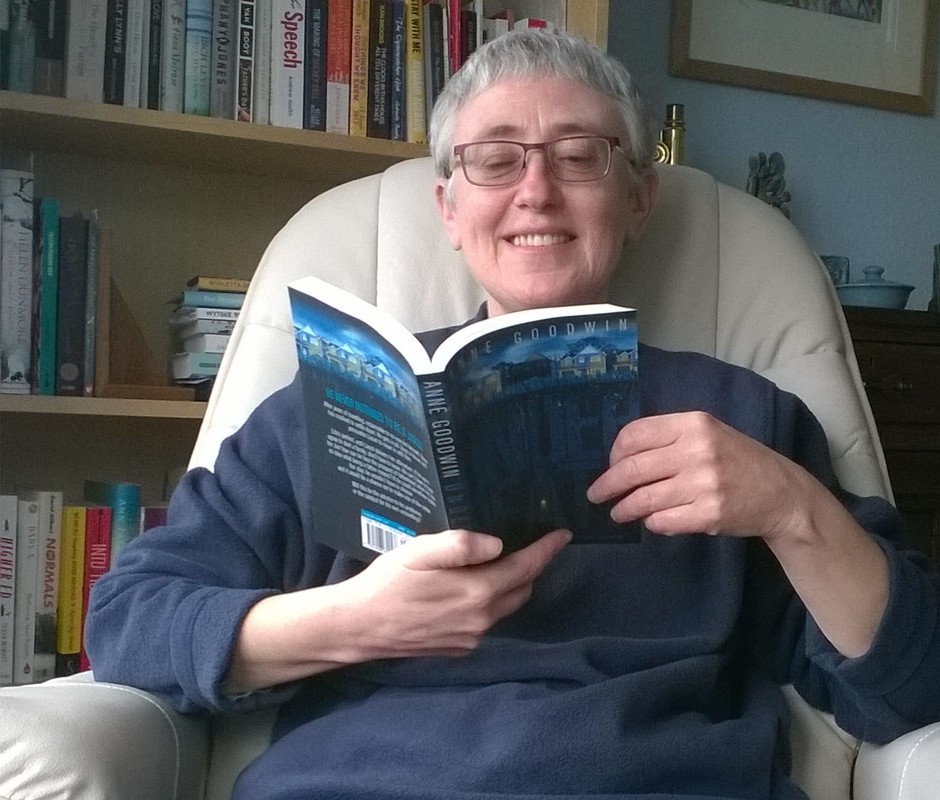

| With a little over two months until the publication of my second novel, the focus has moved from improving the text itself – apart from scouring the proofs for a stray comma or worse – to ways of articulating what the story is about. You’d think that page upon page of carefully selected words could speak for themselves, but no. To interest readers, I have to write and talk about what’s between the covers. |

At the beginning of the novel, the narrator, Steve, meets Liesel in the canteen at work when she pretends to mistake him for another man. A few days later, she accompanies him house-hunting, and invites him to come with her to see an exhibition at the gallery for contemporary art, The Space. While Liesel is moved by the paintings, Steve is (privately) contemptuous (p15):

it pissed me off: the painting was ugly and poorly executed and resembled nothing I’d encountered this side of the womb. To be honest, I found it kind of depressing. I … stood before a canvas that might’ve been meant to represent a bloody massacre or the maws of hell. Or the artist’s grandad’s garage, for all I cared.

Later, in conversation with her friend and colleague – and Steve’s nemesis – Jules, Liesel suggests the art unsettled him (p30):

Liesel stroked my hand. “Steve found the exhibition rather disturbing.”

“No I didn’t. I found it boring.”

“Same difference,” said Jules. “When you’re overwhelmed by emotion your mind switches itself off.”

In the same scene, the two women, who both work in a forensic mental health unit, discuss taking the patients to view the exhibition (p29):

“I don’t know,” said Liesel. “It might be kind of challenging.”

“What’s wrong with challenging?” said Jules. “At least it’s honest. Better than blotting out their feelings with drugs.”

As an art therapist, Liesel’s job is to connect with the patients’ inner worlds not through words but through art. In an attempt to help him understand her work, she shows him (although as a responsible fictional therapist she knows she shouldn’t) a piece by a man who feels emotionally broken (p89):

Liesel took an old shoebox from the filing cabinet. She set it down on the marble-effect tabletop and raised the lid. “Hold out your hands!”

I was tempted to cover my eyes, like in the party game where they blindfold you and put a peeled plum in your hand and pretend it’s Nelson’s eyeball. Yet when she passed me a crumpled brown paper bag, the effect was even more peculiar.

How weird to hold an Action Man again. But … [t]his one had been to war and come home in pieces.

I took out a severed plastic head, a broad-chested torso with a pollarded limb dangling from each corner, two disconnected hands and two disconnected feet, a clump of hair, and four tubes of pinky-yellow plastic that might once have been his forearms and lower legs. I held up a shrunken camouflage suit between my forefinger and thumb.

But it’s on the cellar walls that Steve unwittingly expresses his inner turmoil. Before it becomes a prison, it’s a love nest, a romantic hideaway from the world. When he paints the walls in “intertwining snakes of claret, copper and carnation”, he thinks he’s merely brightening the place up. Liesel thinks he’s doing something similar to the artists whose work was exhibited at The Space.

Although I’m probably closer to Steve than to Liesel in preferring paintings that are pretty to those that perplexing , I do value, at least in principle, art’s capacity to disturb. As I’ve mentioned before, there’s something even more disturbing in an attempt to exist solely in the light. I don’t know whether Liesel ever took her patients to that exhibition, but I recognise the fear, both in her and in her more powerful psychiatric colleagues, that this would entail too much risk. People with severe mental health conditions like psychosis can be extremely disturbed and disturbing, especially those who have behaved in ways that get them admitted to a secure unit. For their sakes, as well as for the sake of those who care for them, and the general public, it makes sense to keep the atmosphere calm.

| Yet it can be a small step from tranquil to tranquillised, to the emotional deadness typical of the old long-stay psychiatric hospital wards. I’ve explored this in academic papers, but I’m not sure if I’ve yet managed to capture it in my current WIP, and hopefully my third novel, Such Dreadful Lies, set in a psychiatric hospital in the process of closing. It does currently have a scene in which a character’s artwork is misunderstood by the staff. I’m wondering if that might furnish my point of entry. |

| I can make a start by using it as my setting for this week’s flash fiction, on the theme of a place where art is not allowed: |

“I’m deeply disappointed.”

My second visit to her office. She was scary enough at my recruitment interview. Now I’ve been “invited” to discuss my expense claim.

“Wasn’t it addressed in your training?”

I could be done for fraud. “I’m sorry I lost the receipt. But you can check the prices at the Tate Modern café.” It wasn’t meant as therapy. An ordinary outing as friends.

“Forget the coffee. Matty returned so agitated they had to sedate her.”

Agitated? She was alive!

But there’s my CV to consider. “Another chance?”

“No more galleries, okay? Art’s too disturbing for fragile minds.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed