Pilgrims by Matthew Kneale

Matthew Kneale has assembled a motley crew of medieval men and women, whose range of reasons for setting off that autumn furnish the modern reader with insights into British society seven centuries ago and the beliefs/superstitions shaping their lives. With no concept of postnatal depression, Matilda Froome, one of the more colourful characters, was deemed to be possessed by the devil when she underwent a personality change after the birth of the first of her eighteen children. Lucy de Bourne, travelling with her cart and servants, must spend months on the road for the chance of divorce from a brutal husband who has commandeered the castle where she was born. Iorweth opts for the dangers of a solitary journey rather than the company of Saxons, such is the history of English persecution of the Welsh. And the racist treatment of the Jews – with a late scene that made me think the author had Brexit in mind when he wrote it – is tragic.

There’s humour too, for example in the currency of chalking up church visits and touching Rome’s relics for specific durations reprieve from purgatory (Hugh calculates he’s got 593 years and twenty-four days off). And squabbles, alliances built and broken, romance. As a keen walker myself, I marvelled at how well everyone managed without the benefit of modern equipment and how infrequently they got lost, something I don’t think was mentioned in Wayfinding: The Art and Science of How We Find and Lose Our Way.

Tom, son of Tom, is the novel’s hero. Embarking on the journey not to save his own soul, or the soul of a friend or relative, but in the hope of releasing his dead cat from purgatory, he’s scorned by his companions initially. Dressed in rags, and having to beg his way to Rome, he proves himself, despite his lowly status as a serf, in his compassion and common-sense, the most noble of them all.

With seven different viewpoints, and lengthy backstories, Pilgrims is less a novel than a collection of closely-linked short stories. I struggled in places to keep track of the multiple characters, but found it overall an entertaining and satisfying read. Thanks to publishers Atlantic for my review copy.

The Yogini by Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay translated by Arunava Sinha

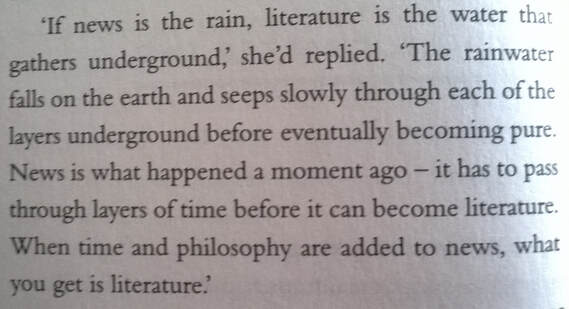

Having bought this novel from UK publishers Tilted Axis in an effort to support small presses in these difficult times, I wish I’d enjoyed it more. While it was great to pay virtual visits to Kolkata and Benaras (known respectively as Calcutta and Varanasi when I was there in the 1980s) and to read a rare translation from Bangla (spoken both in Bengali India and in Bangladesh), I found the characters irritating and the writing flat. Apart from this lovely quote from a flashback to Homi’s interview with the CEO of the media company when asked the difference between literature and news (p12):

So no need to feel guilty if you haven’t spent lockdown writing The Great Pandemic Novel!

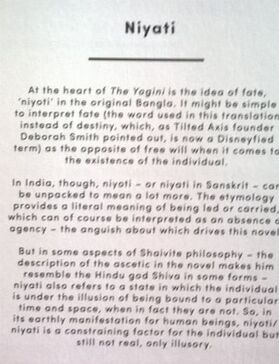

| It may be that I’m too secular in my worldview, but I felt no more enlightened about the meaning of fate at the end of the novel than at the beginning, although this epigraph sets out the stall in a way that makes sense to me outside the boundaries of the novel. My thoughts gravitated more towards attachment issues, as other characters complain about Homi’s lack of commitment, while she goes to pieces when her husband doesn’t take her call (he’s in a meeting) when she rings him at work. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed