| Myeong-chol longed to let himself sob out loud, to stamp the ground or shake his fist at the sky. But, depending on circumstances, he knew that even crying could be construed as an act of rebellion, for which, in this country, there was only one outcome–a swift and ruthless death. And so it was the law of the land to smile even when you were racked with pain, to swallow down whatever burned your throat. |

This collection of seven short stories is unique in being the work of a dissident writer still living in North Korea. Not only Bandi (firefly in Korean) but also the courier who smuggled them out of the country have risked their lives to bring these words to the world. Alongside the compassion we might feel for the hardships of his characters, not totally unfamiliar from my reading of other fiction set in North Korea, one can’t not be moved by the story of how the author, and his collaborators, have brought them to light.

The stories are rife with symbolism of what it means to live under the shadow of such a regime. A two-year-old cries with terror at the enormous portraits of Kim Il-sung and Karl Marx. An old man fights to protect the elm tree planted when he first joined the party, convinced of its magical properties to provide “pure white rice with meat every day, and silk clothes, and a house with a tiled roof” (p68). Larks released from a cage return to the only home they know, while the bricks that have built the municipal government office are described as so red I can’t help wondering if they’ve been tinged with blood. Meanwhile, the arts are distorted, as actors astonish with their ability to conjure “stage truth” and a journalist, who can only write what his masters want to be read, suffers from writer’s block.

If the political message occasionally seems lacking in subtlety, it’s worth remembering that these stories are the work of a writer who could only write for himself. Not for him the critique and feedback we in the West take for granted in developing our craft. We know from an Afterword that Bandi was already part of the writing establishment but, as I know from my own experience of moving from clinical and academic writing to fiction, the skills acquired in one form aren’t necessarily transferable to another.

But Bandi doesn’t need me to apologise for his writing. Although the prose might not set the world on fire, it’s extremely readable, thanks also to Deborah Smith’s fluent translation (which you can read about from her perspective in this article in the Guardian review). While the collection spotlights forbidden stories from a specific place of darkness, they also explore commonalities of the human condition. Alongside the overarching theme of delusion and disillusionment, we find the false self, the shadow of terror, happiness as tyranny and the way that being a parent, perhaps especially a mother, enhances one’s vulnerability.

If that seems unbearably grim, I should add that there are, despite the difficulties of their predicament, moments of compassion between characters and genuine attempts to offer a helping hand. For those of us blessed with governments that are crazy but not that crazy, there are humorous touches, particularly in the satirical story of the grandmother given a ride in the great dictator’s car.

Thanks to Serpent’s Tail for providing my review copy. Readers, I suggest you order yours from your favourite bookshop right now.

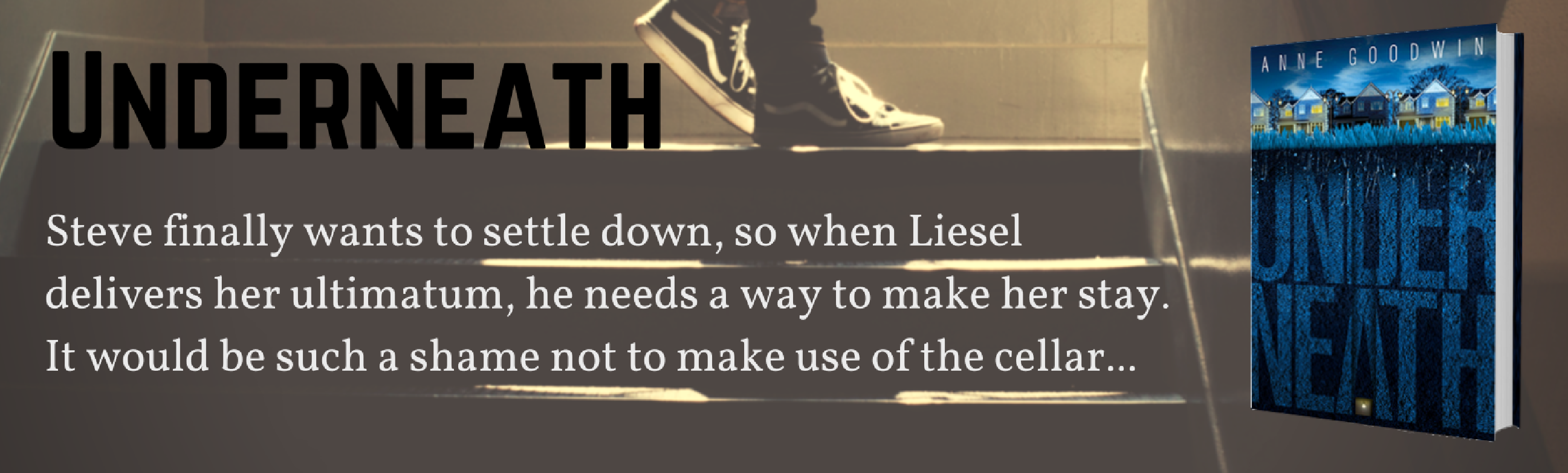

On a much lighter note (even though the story itself is dark, it’s got nothing on the darkness portrayed here), only three more weeks until the publication of my second novel, Underneath, on 25 May.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed