Lily by Rose Tremain

When we meet Lily at seventeen she’s apprenticed to a wigmaker. As one of the owner’s best workers, she’s treated well. But a dreadful secret gnaws away at her. As a murderer, she’s sure she’s destined for the gallows.

When she meets the policeman who saved her life, she’s torn. She appreciates his and his wife’s affection for her – in fact, what she feels for him, despite their age difference is something more – but, as one of London’s prime detectives, will he get her to confess her crime?

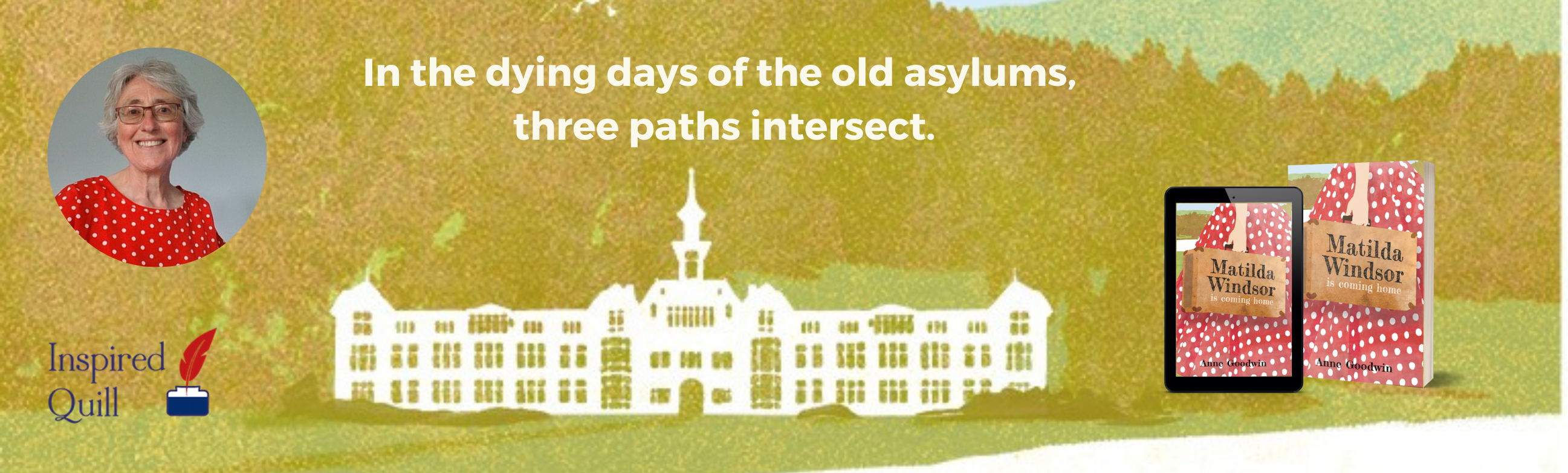

I loved this novel from the first page and looked forward to returning to it each evening. Like the author (see, for example, The Gustav Sonata), I’m interested in nurture, neglect and attachment issues. As you’ll see in my forthcoming novella, the prequel to Matilda Windsor Is Coming Home, I’m interested in institutional abuse.

Afterwards, I wondered if the split between heroes and villains was too artificial: while Lily suffers terribly in the Hospital, most of the other characters she encounters are awfully nice. Perhaps I’m being too picky: what’s wrong with a heartwarming read?

Careless by Kirsty Capes

She can’t tell her social worker because he’s useless. She can’t possibly tell her foster mum. Thank heavens for Eshal, one and only friend.

But the weeks go by and soon it’s crunch time. Eshal’s away in Bangladesh with the prospect of an arranged marriage hanging over her and the man she had sex with is in prison.

I’m the wrong demographic for this novel and, although the stakes are certainly high, I was sometimes bored by Bess. But it’s great to find an author exposing the limitations of the care system and a novel for teenagers presenting abortion as a viable option.

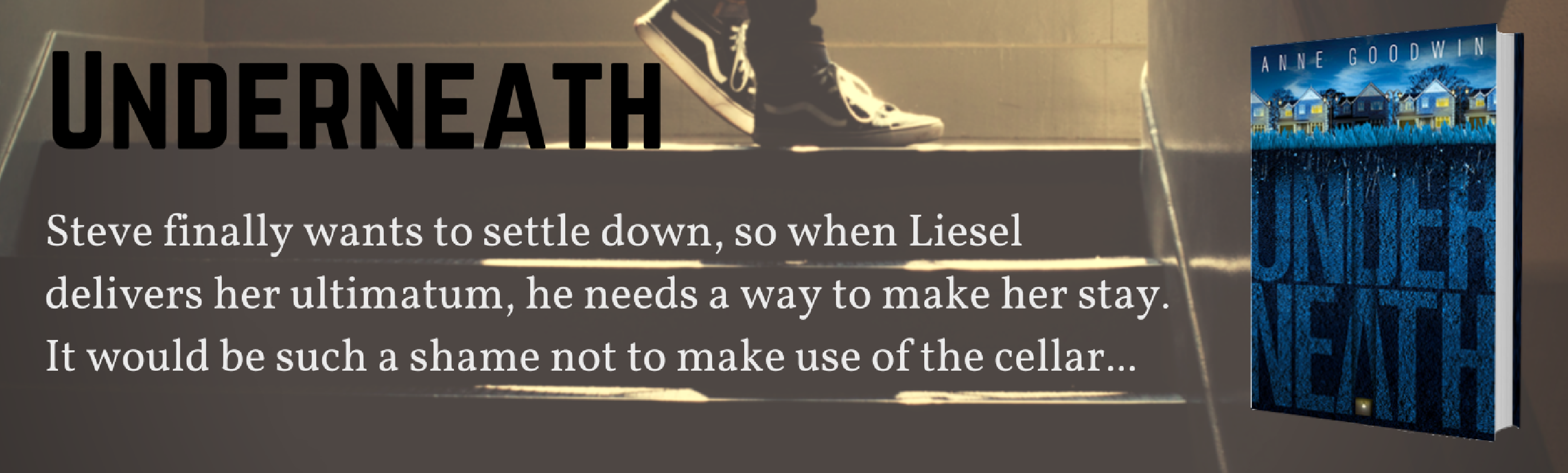

My second novel, Underneath, about a man who seeks to resolve a relationship crisis by keeping a woman captive in a cellar, also normalises abortion, albeit with much less detail.

At day’s end, the girls huddled over their needlework, growing calluses on their fingertips, eyes strained in the dim light. Some knitted scarves for winter, others sewed toys from scraps that they stuffed with straw.

Lily called her doll Bridget after her former friend. The other girls urged her to use more stuffing: the doll was as floppy as puppy ears. Lily replied that she stitched in imperfections lest her handiwork be taken away. But that wasn’t the real reason. The doll represented Bridget as she last saw her: hanging from the rafters with Lily’s scarf around her neck.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed