Dusty Springfield sang about Going Back – the song was played at her funeral – to “the things I learned so well, in my youth”. I carried my story with me for many years but what was it I learned back then? When I started writing notes for a memoir, I knew I too had to go back.

Moving away from home was something we all did after school. In the sixth form we were a close group of nine friends, sharing the boredom of school days, waiting for the excitement of the sort of nights everyone recalls from those vivid, growing-up years; high on the future, bonds strengthened by alcohol, and a new awareness of selves and sexual power.

Then it was university, new lives, friends, marriages, children. But I never forgot the feeling of belonging I had with those friends. Had they felt it too, those three girls and five boys? And when a tragic death ripped the heart out of the group, could we ever be together again and feel the same?

More than 20 years after we’d set off on different paths, I went on a road trip south from my Edinburgh home to visit each of my old “gang”, interviewing them ostensibly for the book but also because I needed to be with them again, to recreate teen me. The “interviews” were some of the best times I’d known, slipping back into relationships that had stayed strong. I drove across England tired, hungover, and happy.

Sian used to yawn when anyone played an Eagles record, but said she’d not heard one since our schooldays without thinking of Mark and me. Julie recalled us all cycling in the dark during that first magical winter together in 1979, “memories I can feel, breathe and touch”. Nick remembered how Mark hated dancing, would only do it “at the end of the night … a lean-on dance!” Adrian couldn’t bring himself to go to the funeral in Hull, our home town. “I wanted to remember the good times. Funerals are horrible sad things.” For Gary, Mark was the brother he never had. “There’s no doubt I’m a lesser person for him not being around and I think about him every day.” Every day.

For two, Mark was more than just memories. Mandy said: “I was driving home and really, really tired. I heard a voice saying, ‘Wake up Mandy, don’t fall asleep.’ It was Mark, his voice, very clear.” Tony saw him. “I bumped into him once, on the landing in my parents’ house. He looked just as he always did, and I shouted at him, told him off. Called him a bastard and said how much he’d hurt everyone. It didn’t feel like a dream.”

I learned that my version of my teen self – clumsy, gauche, ugly even – jarred with my friends’ memories of a pretty, flirtatious yet aloof girl, and I left each of them with a new picture of myself that I really liked.

But the best memory of going back is the night we were all together, sharing a bottle of Laphroaig, sitting in an entangled heap on a hotel room floor, passing round my diaries and laughing like drains. How had I lost sight of the “things I’d learned so well in my youth”? Trust and love. Simple yet priceless. I brought them home with me and then I started to write.

What a process it was. I would walk the boys to school then return home, sit at my dining table in front of the laptop, open my old diaries and step back in time.

I wouldn’t move from where I was sitting, writing and recreating scenes from my diaries. I relived conversations, images, thoughts and sounds, all the joy, pain and domestic banality. I would set my alarm to a half hour before the end of school, and when it went off I would come to, stretch, and then realise I was hungry/thirsty/needed the loo!

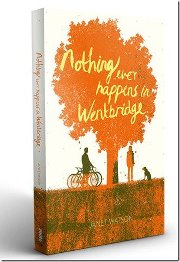

By reliving it, I excised it. Setting it out on a screen, capturing overwhelming emotions and events in a narrative divided into chapters and finally bound in a cover - pages all ordered and numbered - made it a manageable, separate thing. I was ready to let it go, in all its ‘bookness’, and take on a life and meaning of its own.

Undoubtedly, my gravitation towards psychology and then a counselling career came from a need to understand how I lived in denial of love and loss for more than 20 years. My first voluntary counselling job was with Cruse Bereavement Care, working with people who were unable to assimilate their grief in such a way as to live their lives alongside it. As I have moved into more generic work, I saw how Cruse had been my attempt to get close to death, like someone who is scared of heights forcing themselves to stand on a cliff edge. I wanted to remove its sting, become impervious to its pain, to never let it hurt me again.

But of course it will. And does. Writing Wentbridge helped me work through my loss and I really hope it will help people who read it, in some small way. While aspects of loss are universal, our reactions are shaped by our own individual ways of being, and by everything that has gone before. Sometimes we just have to go back.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed