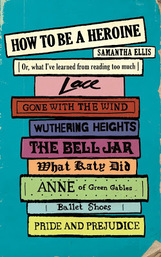

When I ‘won’ a copy on Twitter, I thought I’d nailed this year’s blog post for International Women’s Day. Unlike last year, I wouldn’t have to do search around for my own fictional heroines. Samantha Ellis would do the job for me.

When Rhett sees that [Scarlett’s] hand is scarred, rough from work, sunburnt, freckled, the nails broken, palm calloused, thumb blistered, he spits, ‘These are not the hands of a lady.’ (The most direct result of reading Gone With The Wind again is that I have become more assiduous about using hand cream.) (p88)

About halfway through, it struck me that I was looking to Samantha Ellis the way she was looking to her fictional heroines. Never mind that I might be almost a generation older, I leapt upon the points of connection in our personal stories and felt let down when our trajectories zoomed apart. Would following her journey show me how to be a heroine?

And then, out of the blue, my enthusiasm waned. Was it because I’ve never read The Valley of the Dolls or was it something more fundamental? I thought the writer overly romantic, both in her choice of heroines and the demands she placed on them. Why did she expect a made-up character to show her how to live her life? And why, despite the scope of her own ambition, did she feature so many heroines whose fates were embroiled in the marriage plot? I longed for her to pick someone like Roxanne Cross, the opera singer who holds it all together in Bel Canto, who I’d chosen for my fictional heroine last year.

As I flipped from idealisation to denigration I was mirroring the process that Samantha Ellis had gone through time after time in relation to her heroines. Again and again, she’d start with the memory of perfection only to find, on rereading, the story was full of holes. The search for the answer, the disappointment, the picking ourselves up and searching again: it’s a familiar process. At the time I was reading, I was having the same battle in relation to a piece I was writing on Stephen Grosz’s thoughts on praise for Norah Colvin’s blog.

But this quest isn’t restricted to our reading and writing. It’s so fitting that Samantha Ellis has written this book as a kind of memoir, because this psychological transition from a world populated by heroes and villains to one where we can accept that most people have their strengths and weaknesses is the journey we make from child to adult. Although we might never give them up completely, at some point we have to turn our attention inwards to look for our heroes and heroines.

But it can be scary to rely on our own heroism; there’s always the fear that it might not be enough:

I felt let down when I could see the writer too much at work on a character because it reminded me forcefully that of course I don’t have a writer working on my story, guiding me to safety, bending the laws of reality for me, bringing in a hero to rescue me or transporting me to happier life by the stroke of her pen. (p240)

It’s something of a turnaround when Samantha Ellis settles on Scheherazade as her ultimate heroine, because there are no happy endings in the Thousand and One Nights:

We have to keep making choices, keep transforming. Scheherazade’s stories never end. Every story in the Nights opens a door that leads on to another story. (p244)

just like real life.

When I picked up this book, I was concerned it might be too light and frothy or too deeply erudite. It’s neither. Like novels, like life, it can be approached on different levels: an easy read that, nevertheless, poses as many questions as it answers. It’s one to come back to. What do you think?

By sheer serendipity, my latest short fiction publication has a touch of the Thousand and One Nights about it. Like Scheherazade, Vashila, in Elementary Mechanics, first published in The Yellow Room and now given a second chance on Fiction on the Web, is a survivor, and from the part of the world I might loosely term the Middle East. Unfortunately, like Stephen Grosz’s patients, Vashila has yet to transcend her story. Perhaps her husband can help her.

While you’re composing your comment, why not listen to Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade or, if you prefer pop, another musical heroine featured in the book, Patti Smith singing Gloria? Apologies if I’m tardy at responding to comments in the next few days, but should be properly back online by Wednesday when I’m aiming to post a follow-up to my post on writing about terror. I hope that doesn’t scare you off!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed