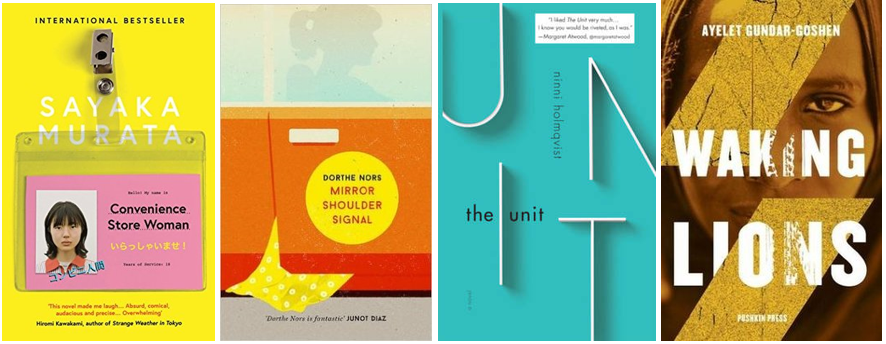

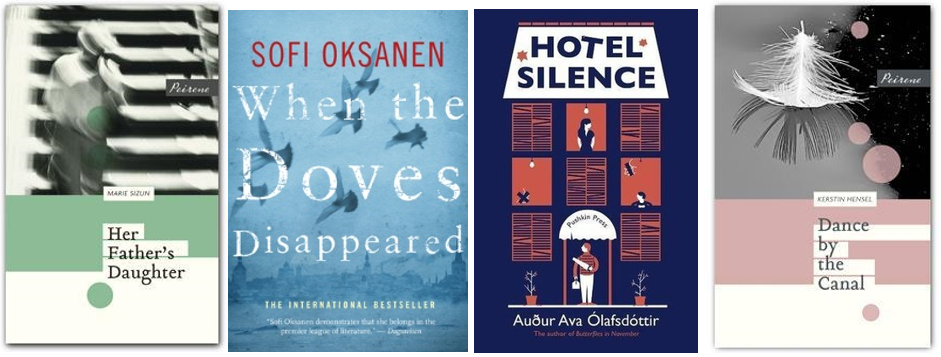

| As August is Women in Translation Month, I’m delighted that my first review of the month is a woman’s translation of a female author’s novel. It’s the twenty-first female translation I’ve read since the end of August last year, and I’ll be celebrating the other twenty – and maybe more – at the end of this month. Meanwhile, you can check out my opinion of The Faculty of Dreams, plus an overview of eight favourites from previous years. |

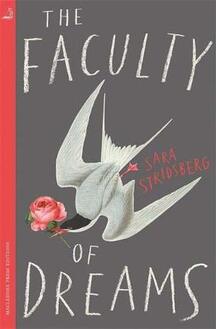

The Faculty of Dreams by Sara Stridsberg translated by Deborah Bragan-Turner

Failing to secure the funds to research reproduction that bypasses the Y chromosome, Valerie leaves university, and her girlfriend, to focus on her writing. Prostitution pays for her seedy hotel room, and her drug habit, and, for a while, she is feted by the media and arty types at Andy Warhol’s Factory. When she shoots him, and almost kills him, she murders her chances of being taken seriously as a writer and thinker too.

There’s a dream-like quality to the narrative as it circles between her poverty-stricken childhood in Georgia, university in Maryland, a Manhattan courtroom where she’s deemed unfit to testify, Elmhurst psychiatric hospital, the hotel room in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco where she dies in April 1988, and a few places in between. The dialogue, including with the narrator, is set out like a play and there are poetic A-Zs of psychoanalysts, presidents, parasites and the like. The author warns the reader that this is a “literary fantasy”, unfaithful to the facts, but there were times when I wanted a clearer boundary between reality and unreality, both in relation to the real-world character’s biography and to the world of the novel, where, for at least half the time, Valerie is deemed insane.

I felt on firmer ground in relation to her childhood, with a narcissistically unstable mother unable to protect her and seemingly more childlike than the child. While Dorothy is sympathetically portrayed, there’s no doubt she’s part of the reason for her daughter’s disturbance, although Valerie herself, ever protective of her mother as neglected children often are, would resist this interpretation. But there are also plenty of pointers to a political rationale for her opinions, as she grows up in a world where male violence abounds.

Why did she shoot Andy Warhol? Like Valerie herself, the author provides material from which we can hypothesise but no answers. I think she felt used that he courted her eccentricity, and dropped her when it became too extreme, or too stale. I think she felt humiliated as a writer, that he never found time to read her play. I suspect the double standards felt unbearable: that a man, perhaps less talented as an artist, could get rich on flouting convention when she sold her body to survive.

This is a sad and thought-provoking story of a woman who won’t compromise in a society where, as ever, the truth can drive you out of your mind. There’s always a snippet of sanity in madness, and a strong strand of delusion in the supposedly sane. Valerie reminds me of some of the people I used to work with, and that scary moment of wondering which one of you is mad. Thanks to Maclehose Press for my review copy. It’s obviously got inside me, as I didn’t plan to write so much about this novel; there’s even a coda below in my flash.

Your mother’s rock, her shining star; you could’ve been a professor, president, you. But you were the seer who saw too much, the dreamer who dreamt her utopia alone. You preached that men grew stiff at the thought of women as stiffs, and peddled your thesis to addicts and whores. Childhood, drugs, poverty and patriarchy drove you crazy, yet you were the only sane one in the room. You could’ve been someone. You could’ve been a rock star. But a black hole swallowed your prospects and talent when you put a hole in the body of a famous man.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed