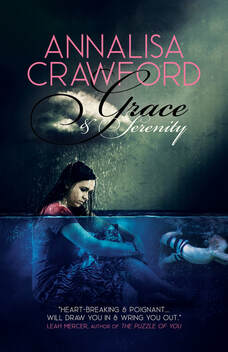

Grace and Serenity by Annalisa Crawford

Soon she is married with a baby, but the home she imagined for the three of them exists only in her head. Neil believes that holding down a job to support his young family exempts him from childcare, housework or an evening at home with his wife. His verbal attacks turn to increasingly vicious physical ones, such that the reader breathes a sigh of relief when Grace finally swallows her pride to return, with a child officially named Sarah, but she calls Serenity, to the family home.

But her difficulties are far from over. When Neil abducts their baby, she fears for Serenity’s life. Yet Neil has turned the tables on her, painting a picture of a neglectful mother unfit to care for a child. Finding solace in drink, Grace seems destined to prove him right and, when her parents take his side, she swaps a comfortable house for life on the streets.

Even reading this on screen – not my favourite way of consuming fiction – I was gripped by this fast-paced debut novel. Annalisa Crawford perfectly captures the disorientation of new motherhood and the gradual erosion of the self in a relationship characterised by coercive control. I really felt for Grace and her predicament and wanted to rush to the rescue. I was less taken with the dramatic resolution, although fans of domestic noir would love it. Nevertheless, I’m happy to recommend it.

Although set in Plymouth, England, and written by a British author, it’s published by Vine Leaves, a small Australian press I hadn’t previously come across. I received an advance e-book copy from the author.

Homelessness doesn’t crop up as often as it ought in my reading, and I don’t think I’ve read anything from the female perspective since Jane Eyre – and she escapes a little more easily than Grace. Another novel that uses an element of magic realism in saving a young woman from her self-destructive behaviours is Blue Tide Rising by Clare Stevens.

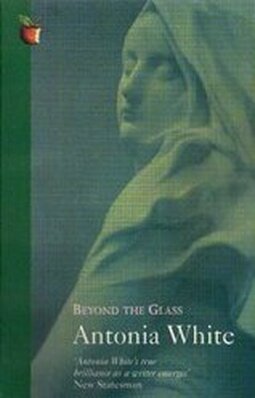

Beyond the Glass by Antonia White

Although her parents are supportive, it’s difficult for everyone that Clara is dependent on them once again. How closely should they supervise her behaviour, given the need for discretion at this delicate time? How long should she rest to recover from her aborted bid for her own family? When should she look for a job?

Clara’s life brightens immensely when she meets Richard at a party and they instantly connect, spending as much time as possible together during his fortnight’s leave from military service in Ireland. Although he’s already partly promised to another woman,he’s prepared to give her up and wait until he can marry Clara. But, even before she’s been able to visit his parents in the country, Clara is in hospital, seriously mentally ill.

Beyond the Glass is the final novel in a semiautobiographical series which began with Frost in May, about a girlhood at a convent boarding school, which I had fond – but vague – memories of reading not so long after it was republished by Virago in 1978. But not having read the two intervening novels, and probably having less tolerance for a languid pace, I was alternately bored, confused and irritated by the references to earlier events during the first half of this book.

But I’m glad I didn’t abandon it as, from the midpoint, Clara’s first-person narrative was transformed into perhaps the best – as in most credible and gripping – account of a flight into mania I’ve come across in fiction or non-fiction. Clara’s tragedy is that at the time she feels most alive, she is the most dangerously ill.

There follow several months in a dismal psychiatric hospital where she is so disturbed she has to be force fed like the suffragettes in jail. The attitudes of the nurses – at least as related from Clara’s perspective – run counter to what might be needed to soothe disturbed minds. Even when she’s well on the way to recovering her sanity, and the doctors are being more helpful, their patronising paternalism would spike anyone’s rage.

My own forthcoming novel Matilda Windsor Is Coming Home, is set in a longstay psychiatric hospital around seventy years later when those institutional attitudes are finally on the way out. If you register for my author newsletter, I’ll keep you updated and, if you’re lucky, you could win yourself a free copy.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed