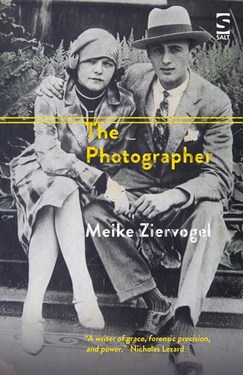

Agatha, a dressmaker, harbours great ambitions for her daughter, Trude. So she’s far from happy when the girl becomes involved with Albert, a flirtatious photographer “from the gutter”. Despite her opposition, the relationship thrives: the couple marry and establish a successful business. But their son, Peter, enjoys trading secrets with his grandmother. When he tells her his parents listen to the Black Radio – and even dance to a satirical anti-Hitler song to the tune of “Lili Marlene” – she takes that knowledge to the police. Having avoided conscription so far, Albert is packed off to the military. The war ends and, along with thousands of others, Agatha, Trude and Peter embark on an uncomfortable journey to the west to finally settle in a refugee camp near Hamburg. There they must learn to build their life anew.

Although set against a backdrop of terrible turmoil during and after the Second World War, The Photographer is a quiet novel about migration, family and life’s inevitable ups and downs. The voice, which flutters between points of view, is simple and understated, which suits the scenes showing Trude and Peter as children but at times I found it overly distancing from the main events. However, it works wonderfully in a later scene in which Albert recalls a disturbing task he undertook on behalf of the military in exchange for an extra bowl of soup. The memory comes upon him like a PTSD flashback, merging with an activity in the here and now, and providing the reader with a possible explanation for his belligerence when he finally rejoins the family in the refugee camp. Zooming in on the what, the reader is left to ponder why Albert must spend several moonless nights raking the soil until the horrific reveal.

As the publisher of Peirene Press, Meike Ziervogel brings (translated) European novellas to Anglophone readers. Her own fourth novel, published by Salt who provided my review copy, is in a similar vein. I don’t think it tells us anything new about the experience of ordinary Germans during the Second World War, it’s an important story that needs to be continually retold, especially now as civilisation seems to have slipped into reverse gear.

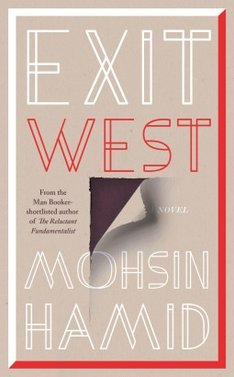

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid

In an unnamed city, presumably in the Middle East, Nadia and Saeed meet at an evening class and develop a relationship. He lives with his parents and prays at least once a day; she, craving independence, lives alone and wears the black robe not for conservative or religious reasons but to discourage unwanted attention. Against the backdrop of social and economic disintegration as the country collapses into a brutal civil war, they become closer, considering marriage until escape into the West becomes a higher priority. At this point, the novel, like its characters, changes direction (p69-70):

Rumours had begun to circulate of doors that could take you elsewhere, often to places far away, well removed from this death trap of a country. Some people claimed to know people who knew people who had been through such doors. A normal door, they said, could become a special door, and it could happen without warning, to any door at all.

I initially read this as a metaphor for migration which, of course, it can’t be otherwise. But within the logic of the novel the doors are genuine portals to a safer space, bringing a layer of magic realism to the gritty tale of burgeoning love within an atmosphere of murder and mayhem. On paying their dues to people traffickers, the young lovers find themselves on the other side of one such door at a refugee camp in Mykonos. From there they make it to London, squatting with migrants from all nations in a luxury apartment block, supported by some “nativists” and the brunt of hostility from others.

Yet this is a surprisingly optimistic tale of identity, migration and adaptation. Both locals and migrants find ways to accommodate to the new reality, although not without some losses on both sides. Differences in their views on sex, religion and loyalty to their native country drive a wedge between Nadia and Saeed.

Narrated in simple language, Nadia and Saeed’s story is interspersed with short glimpses of the lives of unnamed others around the world. Assuming some connection with the overall narrative but failing to find this initially, or even to keep the fragments in mind, I found this an irritation until the final assertion that “We are all migrants through time”, a profound and original conclusion to this quirky parable about our modern world. Thanks to Hamish Hamilton for my review copy.

For my reviews of other novels about migration see The Spice Box Letters; Born on a Tuesday; The Defections; The Fortunes; These Are The Names. For short stories, see breach.

| Her grandmother’s migration from Nazi Germany as a young child has shaped the character of Liesel, the girlfriend of Steve, the narrator my second novel, Underneath. It’s one of the few themes I haven’t (yet) written about for the blog tour, now nearing the end. But you can check out other posts on Steve’s disturbance, the dynamics of his family and the importance of the cellar in the dual meaning of “underneath”, as well as reviews and author Q&As, by clicking on the image. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed