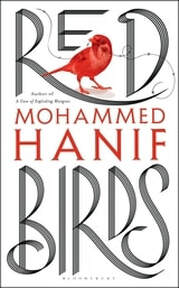

Red Birds by Mohammed Hanif

Add to the mix an unwilling and unqualified doctor, a housewife grieving almost as much for salt as for her son, and a researcher writing a book on the teenage Muslim mind, and things get quite zany. Did I mention that some chapters are narrated by the dog? I’m sure that the previous novel I read by this author was slightly more straightforward than this.

Red Birds isn’t easy to summarise, and the blurb does a better job than me: “a moving, irreverent satire telling important truths about the absurdity of war and the impossibility of peace”. With parallel narratives in the form of internal monologues, I found it hard to engage with initially, and I’m not sure I understood the end. But I enjoyed the middle sections, once we’d moved from the desert to the camp. I also found the references to the soldier’s supposedly preparatory training modules hilarious. Thanks to Bloomsbury books for my review copy.

Trinity by Louisa Hall

These accounts are beautifully realised, and a few would be rich enough for a novel of their own. I found the narratives of three of the four women particularly compelling, and chilling in their portrayal of the limited options for women at the time. Grace is a telephonist at the research station at Los Alamos who, together with other low-status staff, and wives, including one who is heavily pregnant, watches the first test and, the war with Germany now over, hears the scientists’ concerns about it being deployed for real. Sally is an overweight dutiful daughter who drops her “dignified, marriageable degree in art history” (p130) along with her dreams of writing a Great American Novel to become a wife, not long after her twin sister dies of anorexia, leaving little behind save an album of images of agonised Hiroshima victims and a pristine sampler. She becomes Oppenheimer’s secretary shortly before he testifies at the McCarthy witch trials.

Helen, the journalist in the final segment, is in a very dark place herself when she studies the trial transcripts to prepare for the interview. For months, she’s been trying to make sense of her husband’s infidelity, and of her reaction to its coming to light shortly before the birth of their son. This strand picks up and expands on the themes of lies and betrayal of the earlier chapters, the “vague forces of destruction” (p273), and the obvious parallels with Oppenheimer.

Trinity is an extremely intelligent novel, although not an overly intellectual one, that cleverly interweaves the domestic and political spheres. I wasn’t reading closely enough to pick up all the nuances, so was both struck and reassured by Helen’s observation (p292-293):

So many of us … go through our lives making little real effort to understand why we behave as we do, and are therefore forced to act abruptly and with more force, simply to cover up our lack of any good explanation, so that they fly around through the world like so many dull knives, more dangerous to cut with than sharp ones.

As I’m sure you can see, the writing is brilliant too.

At a time in her life when she needs someone to blame, Helen suggests there is an anomaly in Oppenheimer’s being tried not for war crimes but for lying, “for betraying his friends, his wife, and his country” (p310). Afterwards, I wondered if that whole McCarthy paranoia could have stemmed from unconscious collective guilt at the violence that had been unleashed and was too big to understand. Now I’m not sure whether that’s part of what the novel was saying, or I’ve overstepped the mark. Either way, I’ve talked myself into adding this to the year’s favourites. Thanks to Corsair for my review copy.

aa

RSS Feed

RSS Feed