Such a clever book, critics said. In reality, it was a story that thrived on stereotypes. The Brahmins in Himalayan Sunset were stingier and more conservative than those of my real life, the eunuchs more flamboyant, the Western gays more promiscuous, the Indian gays more deeply closeted, the Americans far more ethnocentric than those I came across, and the refugees all worked as dishwashers. Cobwebs in India dangled more freely, mosquitoes here sucked blood more vehemently, and roaches multiplied more aggressively.

Of course, you must stick to pigeonholes in your writing; otherwise, there’s all that talk about inauthenticity.

Although I was amused, the last line bothered me. It might have been true when Naipaul was first published, but for a novel appearing in 2014? When the book continued with Ruthwa’s account of the life of the family servant, the hijra Prasanti, I wondered if this usurping of the transgender character’s voice was somehow a continuation of this joke and the entire novel was intended as a post-modern take on Othering.

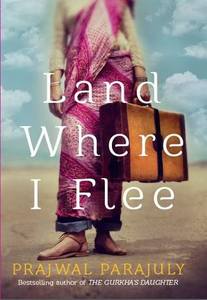

When I wrote my post on my approach to reading for reviews, I neglected to mention that, as well as noting what interests me about a novel, I try to judge it against the writer’s intentions. There’s no point me grousing about the triviality of chick lit if trivial is its USP. Land Where I Flee isn’t chick lit, but I really don’t know what kind of animal it’s trying to be. Comedy? Although, other than the bit I’ve quoted, it didn’t raise much of a smile. Family drama? Exotica? Serious political critique?

There are three stories here I’d have been interested in examining closer: the geopolitics of the Himalayan countries; Bhagwati’s fifteen years in a refugee camp; and the story of Prasanti, and India’s historically contradictory attitudes towards transgender women, from her own point of view. But of course none of these might be the novel the author wanted to write. Thanks to Quercus books for my review copy.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed