The Girl Behind the Gates by Brenda Davies

After four decades of incarceration in a regime riddled with cruelty and neglect, Nora is severely institutionalised, timid and withdrawn. But Janet, a new psychiatrist, takes an interest in her case and, little by little, manages to draw her out. Yet, with the potential for a new life outside the hospital, the future might be as scary as the past.

Despite the (to me) unappealing cover and title - for most of the novel, Nora is more than a girl - the parallels with my own recently published novel drove me to give it a go. I’m glad I did, especially as I admired the author’s unflinching depiction of the inhumanity of mid-twentieth-century asylum culture, even as it was painful to read.

It’s a fictionalised account of the author’s relationship with a long-stay patient she was able to rescue and who wanted her story to be told. Interestingly, we may have overlapped, as, in the book’s acknowledgements, she names a psychiatrist I certainly remember from my workplace.

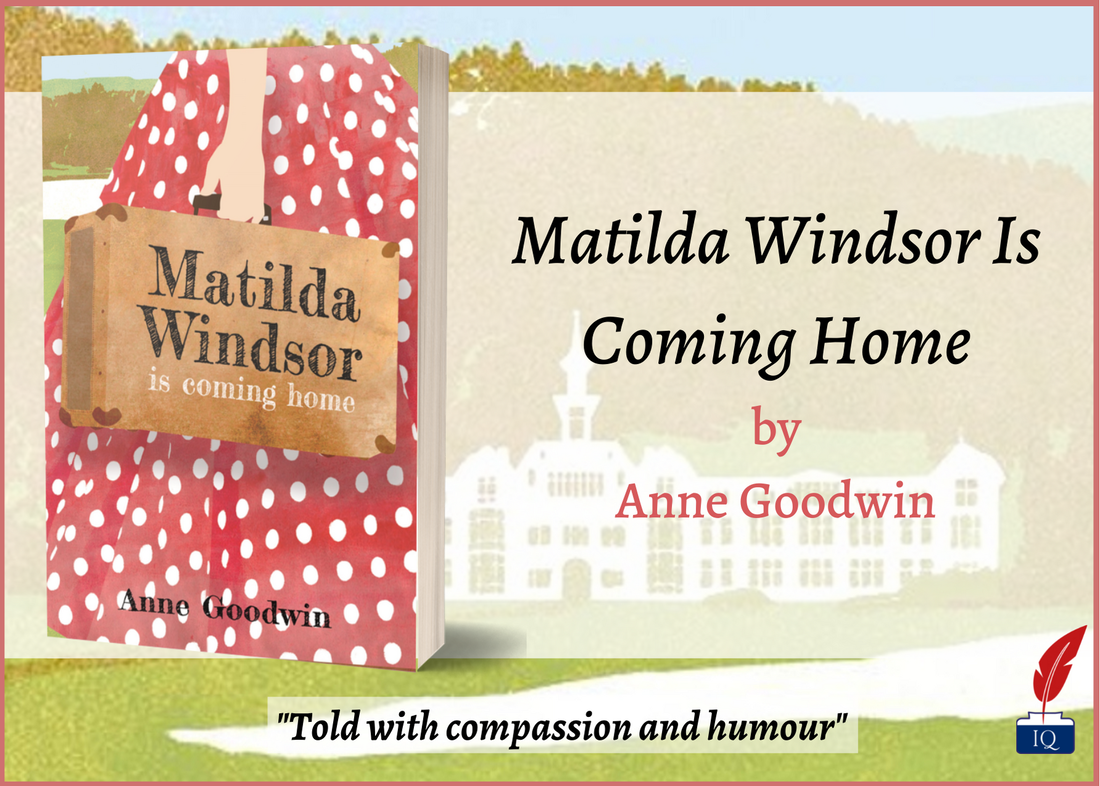

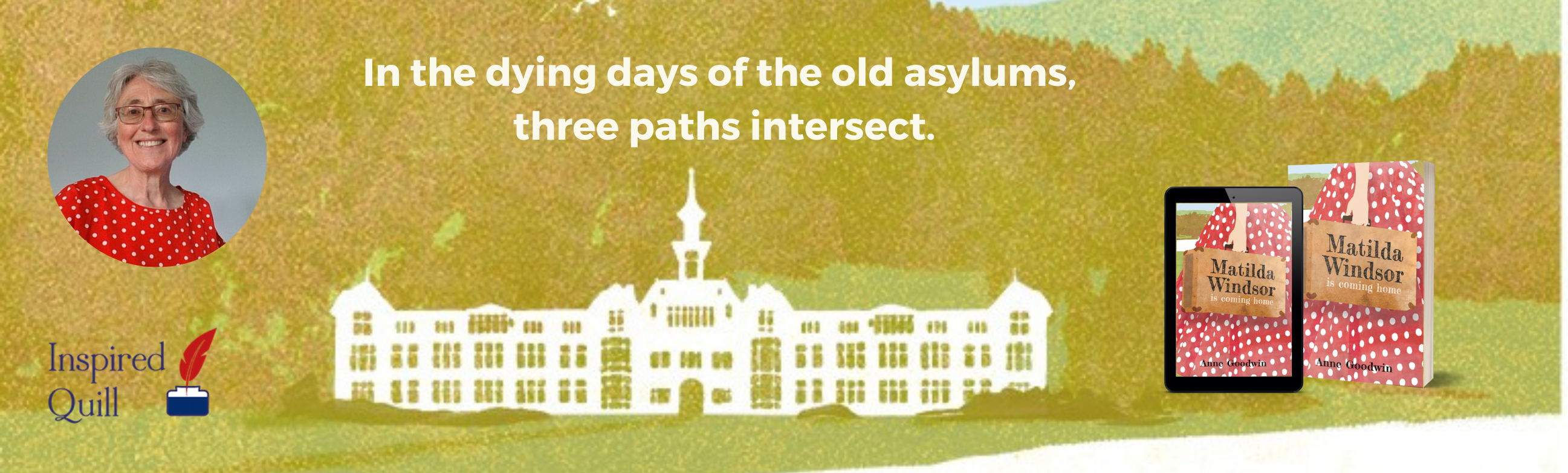

Click on the image to learn more about my novel about a woman admitted to a long-stay hospital in the same year as Nora, after giving birth to an ‘illegitimate’ child. But I only hint at the nastier aspects of her incarceration when the novel begins in 1989.

Stephen from the Inside Out by Susie Stead

Stephen’s childhood seems a recipe for insecure attachment, with an emotionally distant mother who recognises his intelligence while finding him so disturbing she takes him to a psychiatrist at the age of three. As an adult, he loses his only paid job, as a road sweeper, after a couple of weeks. He receives diagnoses of autism and schizophrenia, and is detained in hospital for two decades before eventually acquiring his own flat. In between, he writes poetry, gets married, enjoys classical music and makes friends.

In between sharing Stephen’s story, Susie notes the similarities and differences with her own. As Stephen battles with his dependence on a seriously flawed mental-health system, Susie grapples with her membership of another imperfect institution: the Anglican church.

| With my preference for fiction, I was never going to love this book, but I did enjoy it. I deeply admired her patience in dealing with Stephen’s constant and sometimes contradictory demands, as well as her honesty regarding her feelings of frustration and inability to live up to her Christian ideals. But their relationship can’t be polarised as one between carer and cared-for. In that, it reminds me of another book about a friendship in which one person is identified as mentally ill. (Click on the image for my review of Martin Baker’s book.) |

“Sorry, can’t let you in.” The bouncer thrust the invitation at her.

Anne checked it over: right date; right nightclub. “You’re joking!”

The bouncer flexed his muscles. “Your outfit contravenes the dress code.”

“What?” Anne knew she looked good tonight, even if she didn’t always, in her faux-silk trousers and high-collared blouse.

“The slippers.”

“What’s wrong with them?” What was wrong with him? If only the embroidered dragons on her pink satin shoes could breathe real fire.

“Let’s go!” Hari took her hand.

Anne’s cheeks roasted. It wasn’t her footwear that caused offence. It was her boyfriend’s brown skin.

| So half-hearted apologies that neither of my responses exactly fits the prompt “not everyone fits a prom dress”. I guess not everyone fits thinking about not fitting a prom dress, although Charli’s introduction, featuring a lovely jolly song from a non-binary performer, does seem like an invitation to Diana. However, having dumped my own sartorial angst on her, I’m sharing instead a reading from a moment in which she felt joy in what she was wearing: |

I’ve chosen to write my 99-word story about Matty, to chime with these two reviews. Leaving school at thirteen, she never had a prom either, but she did have a special polka-dot dress.

The bodice crushed my bosoms. Which would burst first, the seams of my dress or me? But I refused to wear that ugly smock for my homecoming. They could keep it for some other unfortunate girl.

Through the taxi window, nothing looked familiar. As we stopped at a palatial building, Sister Bernadette began to pray.

“Am I to go into service?”

A man descended the stone steps to meet us, his gaze on my breasts. I hoped he’d mistake the leakage for a white spot in the pattern of my dress.

“Welcome to Ghyllside.”

The asylum? I’d been tricked.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed