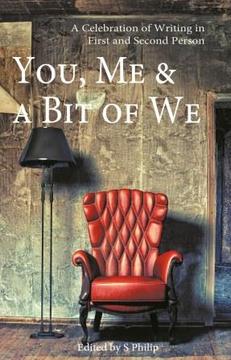

There are around twenty second-person short stories and pieces of flash fiction in the anthology You, Me & A Bit of We. Seeing them together, if not quite reading them back-to-back, it’s striking how many different interpretations of ‘you’ there can be. Even though English has lost the distinction between the singular/familiar and plural/polite forms of the second person to be found in many other European languages, we still manage some diversity in its application, at least in fiction. Hovering between the more familiar first and third person narration, and borrowing bits from both, the second person pulls the reader closer to the story, pushing the identification with the narrator and/or creating the illusion of being addressed directly from the page. Either way, the fictional events portrayed can seem more real.

‘You’ can also serve as an Everyman/woman narrator, challenging the reader to consider how we would react in their shoes. In That Loving Feeling, Sharon Birch brings an original perspective to the familiar scenario of a woman considering leaving her husband. In Meriah Crawford’s unsettling Gonnagetya, the moral dilemma is not one we can stand back and observe: we, as readers, become cringingly part of the problem and possible solution. The generic ‘you’ can also deliver more general truths about causes and consequences, as in Marathon to Perfection by Margaret Gracie.

In some other types of story, the second person coexists with another narrator, with the ‘you’ adopting some elements of ‘s/he’. Some may disagree, but for me The Bedroom Mirror by Anne Fox falls into that category, with an implied omniscient narrator – perhaps the mirror itself – looking kindly on Emil as he prepares for his new life. This Other is more active in Martin Gamble’s Your Final Engagement, an undefined presence who knows all about ‘you’.

Finally, there are the stories where a first-person narrator is addressing a yet-to-be-identified third person who is nevertheless addressed as ‘you’. The gradual revelation of each character’s identity (including the initially ambiguous gender) and the nature of the bond between them is part of this type of story’s appeal. In Laura Dunkeyson’s You Weren’t Heavy, we share the narrator’s empathy and concern for the fragile ‘you’ she carries over the ice and up the steps. In my story, Had to Be You, published by Zouch magazine, the ‘you’ is more menacing and the tie to the narrator feels unwelcome but hard to escape. In another of my stories, In Praise of Female Parts, appearing on Red Fez I’m assuming that the reader’s life situation will be closer to the hypothetical ‘you’ than the narrator, but I don’t think that leads to any loss of empathy. In Your Famous Pink Raincoat by Susan F Giles the ‘you’ form is highly effective in exploring the arc of a relationship from first meeting to break up – very poignant.

I hope this quick romp through what is apparently a complex area of literary theory, is enough to prompt you to share your own views on reading and writing in the second person. And I hope you’ll let me know what you think of some of the stories I’ve linked to here.

I'm aiming to post again next Wednesday, either on how we organise our literary bookshelves being good enough. Hope you'll call back then.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed