| I recently outed myself as a Philistine, by rating one of the 100 all-time best novels 2 out of 5 (“it was okay”) on Goodreads. First published in 1915, The Good Soldier by Ford Madox Ford had sat unloved on my bookshelf for several years when it was chosen for my book group. When the time came to read it, I realised why I’d given up on it the first time round. It’s the story of the relationship between two wealthy couples, and the sexual intrigues and emotional betrayals behind their respectable facades. The novel is considered a master class in the unreliable narrator that has inspired many distinguished 20th-century writers. So why didn’t it work for me? |

It was only when one of the group shared her thoughts about what the narrator was really up to that I could see any value in the novel. Now, while every reader is entitled to her idiosyncratic likes and dislikes, I’ve been bothered before by my bafflement, so I wondered, in this case, whether the limitation were more in me than in the book. If the narrator had been my client, I’m sure I’d have worked somewhat harder to understand him but, even when reading for reviews, I can’t treat perusing a novel as work. In this case, I quickly lost patience with a narrator who plays hard to get.

Frankly, I was bored. But psychoanalytic thinking never takes boredom at face value. It can never be neutral. It must be masking something else.

My thoughts drifted to the research on spoilers and personality style I blogged about earlier this year. The researchers investigated the separate impacts of need for cognition (welcoming intellectual effort) and need for affect (valuing emotion in one’s life) but, as someone who values both thinking and feeling, I don’t believe either can help explain my unwillingness to grapple with The Good Soldier. A discussion in relation to Sarah Brentyn’s essay, Writer Unplugged served to remind me of the richness of the space where emotion and cognition come together. In my understanding of psychoanalytic theory, the greatest depth is in the synthesis of thinking and feeling – but it does take effort. I used to put that effort into my clinical work. I now put it into my own writing. I’ll put it into some of my relationships. But I wasn’t prepared to give it to Ford Madox Ford.

Given that, according to cognitive poetics we approach fiction in the manner we approach real-life relationships, it’s likely that our formative experiences will impact on how we read. Insecure attachment might once have made me more willing than most to battle to engage with an aloof or distant “other”, now I’m probably less willing than average to put in the effort to bridge the gap. I’m sure that not pursuing the unattainable contributes to my current happiness, but my experience of The Good Soldier shows there are times I’ll miss out. How about you? Are you willing to wrestle with a narrator who plays hard to get?

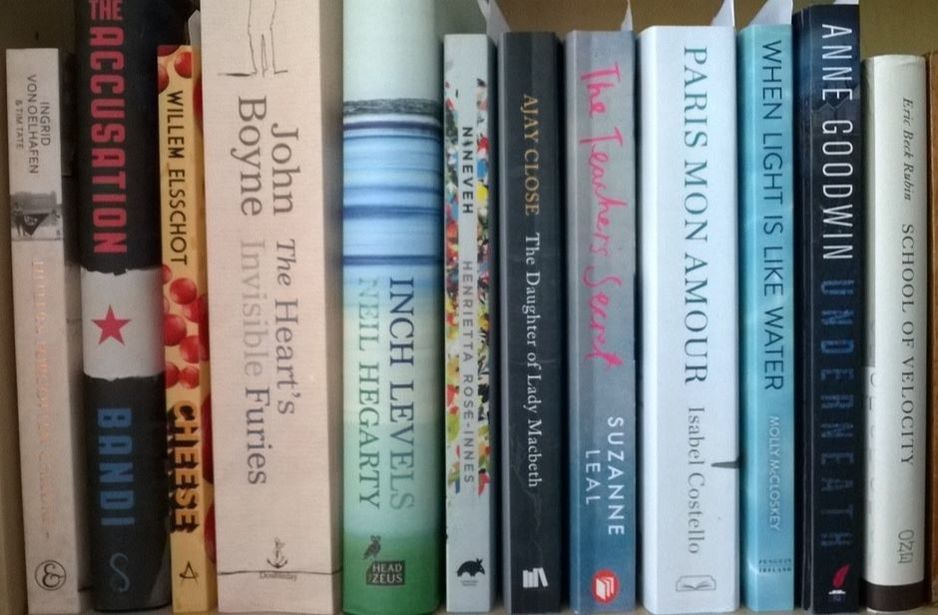

| So, it’s the end of another month, but a special one for me with the publication of my second novel, Underneath. Click on the image for May’s reviews of ten novels and one non-fiction book. |

| I should point out that I drafted this post before discovering that one early reviewer didn’t even consider my novel worth the two stars I gave Ford Madox Ford. But I’m really enjoying the reviews that are coming through the blog tour: the diversity is fascinating and it’s a real honour when readers give it such thought. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed