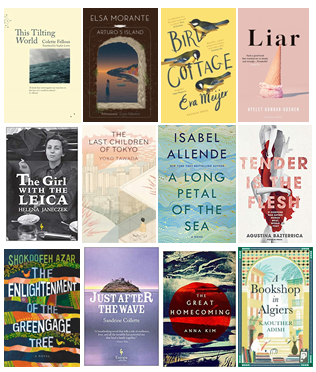

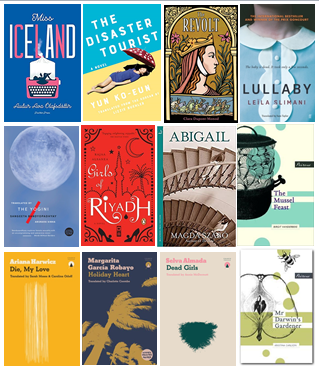

| Between the beginning of September 2018 and the end of August 2019, I read 24 books by women translated into English. Between the beginning of September 2019 and the end of August 2020, I read … 24 books by women translated into English. How could I be so consistent? I didn’t plan it that way! The image on the left shows the covers in the order I read them. Fourteen languages are represented (one up from last year): Arabic, Bangla, Dutch, Finnish, French x 4, German x 2, Hebrew, Hungarian, Icelandic, Italian x 2, Japanese, Korean x 2, Persian, Spanish x5 With twelve publishers represented, that’s slightly fewer than last year: Bloomsbury, Europa Editions x 2, Faber, Granta books x 2, LesFugitives, MacLehose Press, Peirene Press x 2, Penguin USA, Pushkin Press x 5, Quercus, Serpent’s Tail x 2, Tilted Axis |

This Tilting World by Colette Fellous translated from the French by Sophie Lewis and published by LesFugitives, consists of a Tunisian Jewish a woman’s reminiscences on the night after a terrorist attack on a tourist hotel in nearby Sousse. Unfortunately, although I was interested in learning about her culture, I couldn’t engage with the authorial intrusion.

Despite an attention-grabbing opening, in which two children have been murdered by their nanny, Lullaby by Leïla Slimani, translated from the French by Sam Taylor and published by Faber & Faber, is a quiet novel about the fragile dynamics of the employer-employee relationship when the task is emotionally difficult to delegate and the workplace is the family home.

The Yogini by Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay translated from the Bangla by Arunava Sinha and published by Tilted Axis, was a frustrating read about a woman stalked by a yogi claiming to be the embodiment of her fate, partly redeemed by a wonderful quote about the difference between news and literature.

Girls of Riyadh by Rajaa Alsanea, translated from the Arabic by Rajaa Alsanea and Marilyn Booth published by Penguin, is a light read about love, liberty and restrictions on four young women from Saudi Arabia’s upper echelons.

Holiday Heart by Margarita Garcia Robayo, translated from the Spanish by Charlotte Coombe and published by Charco Press, is an unflinchingly honest and wryly humorous novel about marriage, migration, snobbery and social class, and the hollow magnetism of the American Dream.

Die, My Love by Ariana Harwicz translated from the Spanish by Sarah Moses and Caroline Orloff and published by Charco Press is about a young mother on the knife edge between madness as mental illness and madness as rage.

Five featured 20th-century conflicts, including

Arturo’s Island by Elsa Morante, translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein and published by Pushkin Press, is a coming-of-age story with themes of masculinity, misogyny, Oedipal conflict and jealousy about a boy growing up almost feral in the years leading up to the Second World War.

The Girl with the Leica by Helena Janeczek, published by Europa editions and translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein, is about Gerda Taro, a feminist photojournalist, who died documenting the Spanish Civil War, from the perspectives of two former lovers and a close female friend. Also kicking off with the Spanish Civil War, A Long Petal of the Sea by Isabel Allende, translated by Nick Caistor and Amanda Hopkinson and published by Bloomsbury, is a family saga spanning six decades up to the defeat of Pinochet in 1990s Chile. Neither of these engaged me as much as I’d hoped.

The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree by Shokoofeh Azar, translated from the Persian by Anonymous (the name withheld for safety reasons) and published by Europa editions, draws magic realism to explore mourning and madness amid the cruelty and chaos of Iran’s Islamic revolution, along with a meditation on the power of storytelling to make the unbearable slightly easier to bear.

The Great Homecoming by Anna Kim, translated from the German by Jamie Lee Searle and published by Granta, is stuffed with fascinating information about the psychotic Korean divide but, branded as a novel, it seems unable to decide whether it wants to be fiction or non-fiction.

A Bookshop in Algiers by Kaouther Adimi, translated from the French by Chris Andrews and published by Serpent’s Tail, is about two young men and a city bookshop, eighty years apart. Edmond Charlot is building it from nothing; Ryad is on a bogus internship to assist in its demise.

And one went much further back in history:

The Revolt by Clara Dupont-Monod, translated from the French by Ruth Diver and published by Quercus, examining the war-torn lives of Richard the Lionheart and his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, in twelfth century Europe, didn’t engage me as much as I’d hoped.

Four addressed an alternative present or hypothetical future:

The Last Children of Tokyo by Yoko Tawada, translated from the Japanese by Margaret Mitsutani and published by Granta books, is a dreamlike fable about how the older generation has stolen their children’s future by poisoning the planet – and perhaps some other themes more specific to Japanese culture that I didn’t quite get.

Tender Is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica, published by Pushkin Press and translated from the Spanish by Sarah Moses, is a refreshingly light, but not lightweight, dystopian novel about cannibalism, with themes of animal welfare, our collective disregard for humans deemed different to us, alongside the dehumanising culture of some types of work.

Just after the Wave by Sandrine Collette, translated by Alison Anderson and published by Europa editions, is heart-breaking cli-fi novel about grief, guilt, survival and abandonment.

The Disaster Tourist by Yun Ko-eun, translated from the Korean by Lizzie Buehler and published by Serpent’s Tail, is a slipstream eco-thriller about poverty, capitalism and the ethics of tourism.

One is nonfiction

Dead Girls by Selva Almada, translated from the Spanish by Annie McDermott and published by Charco Press, is the non-fiction story of a fiction author’s attempt to uncover the truth behind the murders of three young women in provincial Argentina that occurred during her teens.

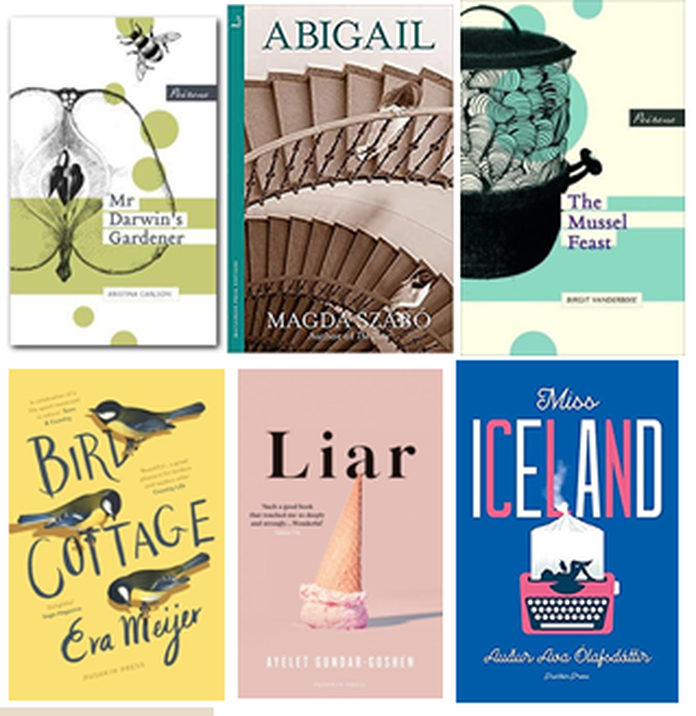

My six overall favourites, irrespective of period or genre, are

Bird Cottage by Eva Meijer, translated from the Dutch by Antoinette Fawcett and published by Pushkin Press, is a heart-warming – but unsentimental – novel about an inspiring woman: English eccentric, lay scientist, talented musician and ornithologist with the courage to live life on her own terms.

Mr Darwin’s Gardener by Kristina Carlson, translated from the Finnish by Emily Jeremiah and Fleur Jeremiah and published by Peirene Press, is a delightful novella, about community, religion, belonging and and unbelonging, composed in a collective voice.

In Liar, translated from the Hebrew by Sondra Silverston and published by Pushkin Press, Israeli author Ayelet Gundar-Goshen, brings a light touch to the serious consequences of stretching the truth.

Miss Iceland by Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir, translated from the Icelandic by Brian FitzGibbon and published by Pushkin Press, is an upbeat yet poignant novel set in the 1960s, about a young writer and her fashion-designer friend fighting through the snares of sexism and homophobia to follow their dreams.

Abigail by Magda Szabó translated from the Hungarian by Len Rix and published by MacLehose Press, is a boarding-school coming-of-age story with a difference, raising questions about dissenting voices during times of national emergency (in this case, Hungary’s role in Second World War) and how to keep adolescents safe without clipping their wings.

In The Mussel Feast by Birgit Vanderbeke, translated from the German by Jamie Bulloch and published by Peirene Press, the cracks in the facade of a superficially happy family are gradually revealed as a teenage girl waits, along with her mother and brother, for her tyrannical father’s return.

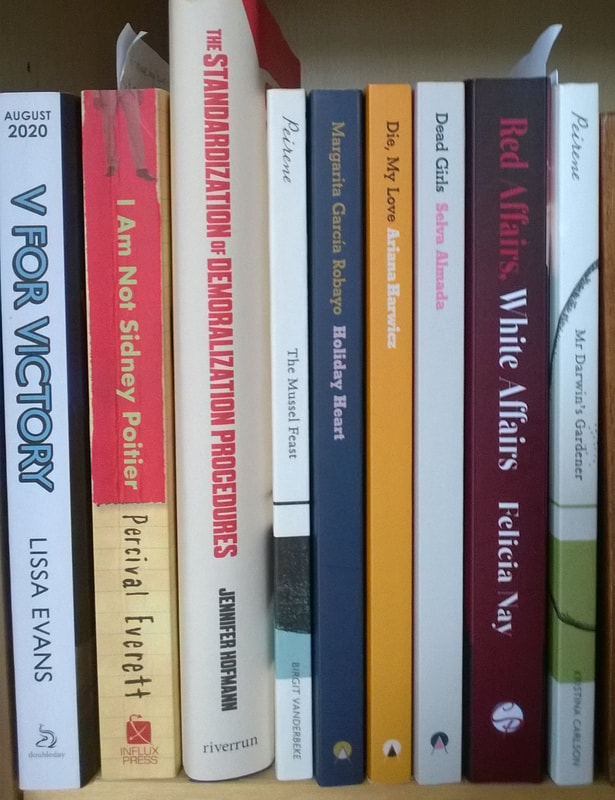

Not all recent reads were translations.

Click on the image below to see all August’s posts and reviews.

“We can’t call them that!”

“Why not? They’re lemony. They’re puffy. They’re not lemon crisps.”

“Why not? Because it’s a term of abuse.”

“Nonsense! No-one thinks that anymore. Homophobia’s consigned to history. Along with racism and blaming women for being raped.”

“Remind me of our demographic.”

“Middle Englanders. Conservatives with a C both big and small. People who’d never dip a biscuit in their tea.”

“Unless it’s a ginger snap?”

“They don’t buy ginger snaps. They’re for the hoi polloi.”

“Royalists?”

“To the core. Loyal to Prince Andrew. Think Harry should be shot.”

“Then let’s call them Lemon Queens.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed