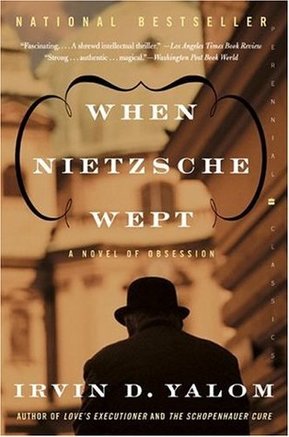

| In 1882, in a wintry Vienna, two brilliant minds connect. One is an ambitious, although rarely read, philosopher; the other is a highly respected diagnostician and doctor to the rich and famous. The men are drawn to each other’s ideas but, although one’s a bachelor and the other a married father of five, they have more in common than they realise. Both men’s obsession with a much younger woman is threatening their well-being. |

The philosopher – obviously, from the title – is Friedrich Nietzsche, and the doctor Josef Breuer, one of the founding fathers of psychoanalysis. With Sigmund Freud, at that time still undertaking his medical training but collecting dreams as a “hobby”, also having a role as Breuer’s sounding board, the novel provides an alternative history of the origins of psychoanalysis. Although Breuer and Nietzsche never met, the philosopher’s perspective on the human condition and methods of self-analysis anticipates, at least in Irvin Yalom’s version, much of what is attributed to Freud.

When the main characters meet, Breuer has already stumbled upon a form of talking therapy. His treatment of Bertha Pappenheim – made famous in psychoanalytic circles under the pseudonym Anna O – involved a form of free association which she called “chimney sweeping” to uncover the origins of her “hysterical” symptoms. (Nietzsche takes this a stage further by showing that it’s not so much a matter of origins but meaning, p220.) But Breuer hasn’t considered this in a wider context until he meets Nietzsche and is both thrilled and disturbed by his unconventional beliefs (p75):

To say that hope is the greatest evil! That God is dead! That truth is an error without which we cannot live! That the enemies of truth are not lies, but convictions! That the final reward of the dead is to die no more!

Breuer is not being entirely honest when he offers himself as Nietzsche’s disciple. He hopes that, by sharing his own distress, he will inspire the philosopher to do the same. But, like anyone undergoing therapy as part of training, he has to bring genuine difficulties and, before he knows it, he’s hooked (p199):

Breuer now fully acknowledged his own despair and his need for help. He stopped deceiving himself; stopped pretending he was talking to Nietzsche for Nietzsche’s sake; that the talking sessions were a ploy, a clever strategy to induce him to talk about his despair. Breuer marveled at the seductiveness of the talking treatment. It drew him in; to pretend to be in treatment was to be in it. It was exhilarating to unburden himself, to share all his worst secrets, to have the undivided attention of someone who, for the most part, understood, accepted, and seemed even to forgive him. Even though some sessions made him feel worse, he unaccountably looked forward to the next with anticipation.

Nevertheless, Breuer has not found this transition to “patient” easy as he must face some painful questions about himself. What is he avoiding by his workaholic attitude? What deeper anxieties do his obsessional thoughts about his former patient, Bertha Pappenheim, obscure?

Frustrated at the slow pace of change, in a manner that many on either side of psychotherapy will recognise, Breuer demands Nietzsche tell him how to break free of his obsession. I imagine Yalom, a highly renowned American psychiatrist and existential therapist, would have enjoyed sending his characters on a wild goose chase through various cognitive-behavioural techniques until, speaking for both, Nietzsche declares (p220):

Our last sessions have been false and superficial. Look at what we tried to do: discipline your thoughts, control your behavior! Thought training and behavior shaping! These methods are not for the human realm! Ach, we are not animal trainers!

There are other touches of humour (such as when Breuer expects his wife to acquiesce to his bid for freedom, and understand the convoluted reasons behind it) but, overall, I found When Nietzsche Wept a poignant story of wounded healers and second chances, and the despair and vulnerability that sometimes coexists with success. Although the pairing of philosopher and doctor disregards the boundaries of contemporary psychotherapy, their encounter illustrates many of the ways exploratory therapy differs from an ordinary conversation (which is sometimes difficult for the uninitiated to grasp):

- confronting “negative” emotions, including despair

- a search for the “truth” rather than comfort

- looking below the surface of presenting problems

- the therapist supports the client to find their own way of becoming the person they are

- speaking freely without censorship

- it’s difficult, painful but also potentially rewarding,and even joyful

- the therapist also learns from the patient

- the relationship is key

In an afterword to my copy (Harper Perennial, 1992/2003), the author explains that he wrote this as a teaching novel, but don’t let that put you off! Irvin Yalom knows how to spin a story, and When Nietzsche Wept is an absorbing read.

| With my list of fictional therapists now approaching sixty, I ought to have stumbled upon this one sooner, so thanks to Erin Stevens for flagging it up. And in good time for my forthcoming posts on real therapists fictionalised, which will be the third in my series at The Counsellors Cafe magazine. |

| My characters are named after historical warriors, so the latest response to flash fiction prompt is the perfect opportunity to introduce that might-be novel in the form of a 99-word story. |

Independence Day

Whose is this voice that thunders in her head? Who will she become if she listens? Yet someone must lead, so why not Joan? What she lacks in years, she brings in passion.

Standing in the stirrups to adjust her seat in the saddle, she channels the spirit of her namesake. Her armour might be card, but her lance is real, and Joan knows how to use it. Not that she thinks she’ll need to today as she steers the procession through cheering crowds. Skirmish is rare on Independence Day, but a woman warrior is always primed for action.

| Thanks for reading. You might also like my tribute to The Warrior Women of Ireland which is a late addition to last week’s post sharing a secret on my second novel’s first birthday. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed