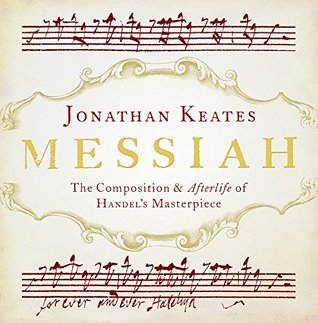

| Even if you’re not a fan of Baroque music, you’d probably recognise at least one of the magnificent choruses from George Frideric Handel’s Messiah. If not the jolly “For Unto Us a Child Is Born”, perhaps the main justification for its popularity at Christmas, then you must know the exuberant “Hallelujah”. But there are fifty-one other choruses and solos that make up the three-hour long oratorio. This beautiful book tells the story of its composition and musical afterlife. |

An oratorio, as I also discovered, is a specialised musical genre, popular in Europe, but introduced to England by Handel himself in the 1730s. The religious counterpart of opera, although delivered minus the acting and suitable for secular settings, it required further adaptation to suit the Protestant sensitivities of English and Irish audiences. The narrative arc typical of the form is less pronounced in the Messiah, but there’s nevertheless a progression through the Christian story across the three parts from prophecy to the cruelty and mockery of the crucifixion to the resurrection.

That the latter is presented as literally miraculous, rejecting more metaphorical interpretations of Christian doctrine creeping in with the Enlightenment, is down to the librettist Charles Jennens, a ‘non-juror’ who stood slightly apart from public life due to his refusal to swear an oath of allegiance to George I, of the house of Hanover.

Handel was himself of German origin, but settled in London in 1723 and, although a celebrated musician, was reliant on royal patronage to survive. Yet he was no unworldly artist, but an entrepreneur with an eye on the market in a manner we’d recognise today.

At its premiere in Dublin on 13 April 1742, for reasons of health and safety in the crowded music hall, Ladies were requested not to wear the fashionable but bulky hooped skirts and Gentleman to attend without their swords. I enjoyed reading about the politics of performance and the complexities of the role of women and the authority of the church. (It seems to be just as crazy today when an atheist is welcomed onto church premises to sing secular music while believers are denied the sacrament of marriage under its roof if they dare to love a partner of their own sex.)

London was initially less enthusiastic in his reception where, sensitive to religious sensibilities in the capital, he presented it untitled. The work eventually found an appreciative home in annual charity performances in association with Thomas Coram’s new Foundling Hospital. But musical biographers and historians, including the author of this book, lament the populism and mythologising that accrued across the Georgian and Victorian periods, with Messiah eclipsing the composer’s other works and large-scale performances pandering to the nationalism and religious piety of the age distorting Handel’s original intentions. However, the last few decades, with a renewed interest in Baroque instruments, has prompted a more authentic revival of the work with smaller choirs of around twenty singers (which would rule out amateurs like me).

Published by Head of Zeus (who provided my review copy), Messiah is part of the Landmark Library of “handsomely illustrated [books with] … a text of 25,000 words devoted to a crucial theme in the history of civilisation” which, at the reasonable price of £16.99 for a 190-page hardback, would make a lovely gift for any music lover. I’m pleased to be able to post my review on the anniversary of the oratorio’s first performance, although I’d better get it out of my head before going off to sing Faure’s Requiem tomorrow. (If you haven’t yet seen it, you can also read my post Struggling Soprano No More? hosted by Gulara Vincent.)

I thought about this recently when I decided not to review the novel I’d just finished. Seemingly intended as a warmhearted meditation on fatherhood, it told of a little girl who, following the death of both parents, and with no other living relatives, is adopted by her father’s estranged brother, a single man with serious anger management issues. I’ve met this situation on the page before, where a young child who, for whatever reason, needs above-average parenting skills, is paired with an unlikely character and, by showing him how to love her, saves them both. I find the reversal of roles between parent and child quite disturbing, and yet such stories are often popular with readers. I put it down to the power of the Messiah myth.

I don’t deny that parenting can bring out the best in people and I’m all for giving offenders another chance. But wounded children and wounded adults need help to heal and I don’t think we can get away with putting them together and hoping for the best. Expecting a child to put the world to rights is rather like voting for regime change based on the illusion that anything’s got to be better than what we’ve got. Perhaps unconsciously I knew what I was doing when I put the Messiah in that messy first draft of a story about a woman who decides having a baby is the best response to her best friend’s violent death.

The psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion is particularly renowned for his studies of how people brought together to carry out a task get distracted because of the anxieties of working in a group. One way this is manifest is in what he called basic assumption pairing in which the members behave as if it’s agreed that a coupling between members will produce a metaphorical Messiah; if you’ve ever been in a meeting where, after failing to resolve an issue, everyone agrees that the best way forward is to set up a working party that will come up with the answer. Oh, the relief at being able to set the matter aside and go back to being nice to each other!

Hope, even unrealistic hope, is helpful if it enables us to work for a better future. But, in the extreme, when hope morphs into the Messiah myth, whether in the form of political reform or an actual baby, it smacks of irresponsibility. But hey, nothing to do with me, I’m off to sing.

| I’d forgotten I had written about creation myths a couple of years ago, until Charli Mills made that the topic of the latest flash fiction prompt. Although I’ve missed the deadline, I can’t resist posting my 99-word story right here. On a similar theme you might like to read my short story, “The Invention of Harmony”, if you haven’t done already. |

God could understand why Adam envied the birds. Their vantage point above the earth, the way they’d glide from tree to tree.

“It’s not that,” said Adam. “It’s how they sing your praise.”

So when God created Adam’s wife he gifted her with melody. And all was harmony until she met the Serpent. “Not all music belongs to God,” he hissed. “There are other words. Other tunes.”

Eve shrugged. “God’s music is the best.”

“You cannot know, until you’ve tried some other.”

So Eve sang of birds and bees and apple trees, and God banished her from his garden.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed