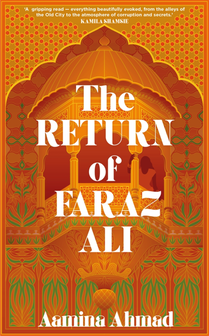

This isn’t a police procedural, although we do get an insight into the rough-and-ready methods of the law keepers in late 1960s Pakistan. It isn’t a crime novel, although we are left with some idea of how the girl was killed. The scope is much more ambitious, addressing corruption and injustice in a country in the process of splitting apart.

From the opening in 1968, the author takes us back to the Second World War and forward to the creation of Bangladesh. Faraz’s father, fighting for the British Empire, only recalls his son’s existence when he fears he might die. The boy’s separation from his family – although his father gives him an education he never publicly claims him as his son – echoes the political splits of Pakistan from India and the eventual independence of what was previously East Pakistan.

It’s also a novel about the politics of gender and class or caste. Although skilled in song and dance, the Kanjar girls and women are destined for sex work. Mothers have no choice but to train their daughters to take up the profession: when their own bodies are wasted the next generation will ensure they don’t starve. Faraz’s sister has escaped the ghetto through the patronage of a wealthy lover and a career in film, but she’s never respected and her good fortune can’t last.

Thanks to publishers Sceptre for my advance proof copy.

I love reading fiction set in the Indian subcontinent and it was an extra boost to follow Faraz to glimpse the fight for Bangladesh’s independence from the ‘other’ side. (Follow the link to my 99-word story Ekushey February for more.)

Another bonus, however, was finding themes fictionalised in my novels: a woman keeping her origins a secret in Sugar and Snails and a brother and sister separated for decades in Matilda Windsor Is Coming Home.

| I’ve revisited a scene from one of these two novels for my response to this week’s flash fiction challenge. If you’ve read them, you might be able to tell which one. It feels like cheating, but I doubt I’d have got there otherwise: how often do you come across a story based on “baby ducks ate my lunch”? I’m looking forward to see how others have managed it when the compilation is posted in the middle of next week. |

A line of custard-yellow pom-poms waddling to the water: those ducklings are braver than me. I envy them a mother they can place their trust in: she’ll ensure they can float before they take wing.

I’ve let Simon think I’m scared of flying, when my terror is of drowning in shame. So we sit on this bench between the tennis courts and boating pool, not eating our sandwiches, chewing over everything save why I can’t follow him, why I can’t board a plane. I wish I could be better, kinder, more generous. I feed the baby ducks my lunch.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed