The Uncommon Life of Alfred Warner in Six Days by Juliet Conlin

His early years in Germany were tragic: both parents dying in an accident when Alfred was six, he was separated from his siblings when the superintendent of the orphanage to which he was destined discovered he was a bit odd. Saved from the lunatic asylum, he pitches up in a much more pleasant Jewish children’s home, although he’s not of the faith. Years later, he makes it to Scotland although not, as originally intended, via the Kindertransport, but as a German prisoner of war. Eventually he settles in Britain, marries and is gainfully employed as a gardener.

What makes Alfred Warner’s life uncommon, is less the historic events he witnesses, but as someone who, from early childhood, hears voices of people who are not physically present. Alfred’s experience of the three women who benignly occupy his mind, supporting and guiding him through decisions, large and small, is contrasted with the experience of his granddaughter, who also hears voices, but of a persecutory nature.

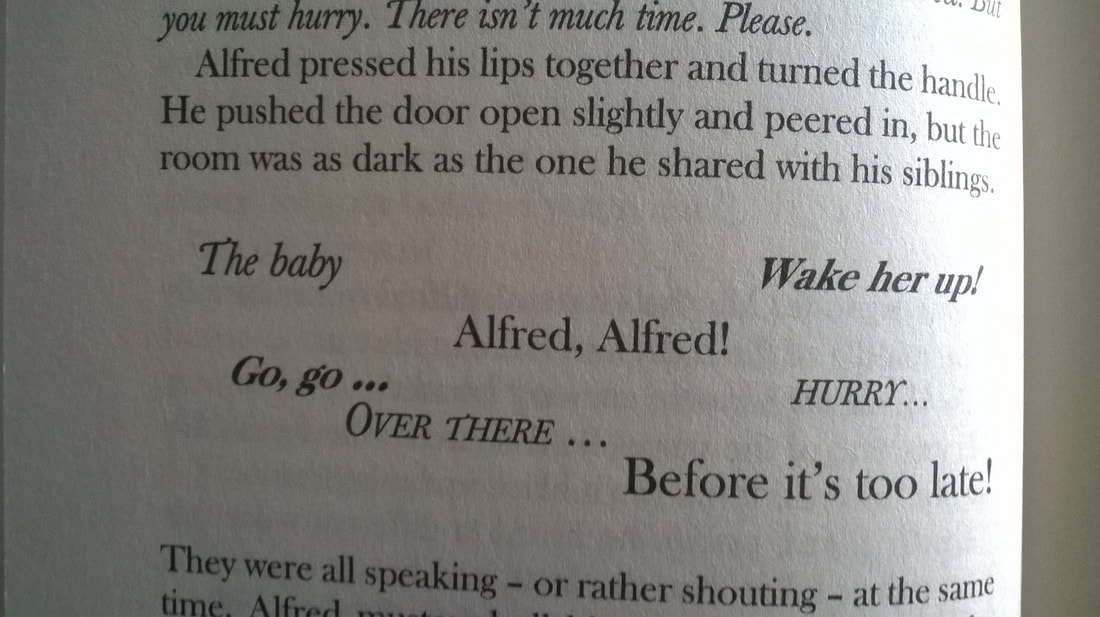

If you read my previous post on the unconscious, dreams and hallucinations in fiction, you’ll probably realise that it was this that attracted me to Juliet Conlin’s second novel. Although normally averse to postmodern textual devices, I really enjoyed how the strangeness of Alfred’s first encounter with his “voice women” is shown through the arrangement of the text on the page.

The Uncommon Life of Alfred Warner in Six Days has also provided another fictional therapist for my collection in a short scene when Brynja is dismally failed by a woman who starts the session by telling her to remove her shoes in order not to dirty the carpet. Unfortunately for Brynja, her therapist lacks the necessary patience for forming an alliance with an adolescent, or any hard to reach client, telling her, “If you don’t cooperate, there’s no point in you being here, is there. Then you’re wasting both our time.” (p279).

Despite the complex structure (three point of view characters, with one going backwards in time), the novel is a comfortable read if, at over 400 pages, rather long. Thanks to Black and White Publishing for my review copy; my first from this publisher but probably not my last.

The Giddy Career of Mr Gadd (Deceased) by Marie Gameson

When she meets Fred Fallowfield, her former history teacher now suffering from dementia, he’s convinced that a story she wrote at school, “The Giddy Career of Mr Gadd (Deceased)”, contains the key to resolving the chaos in his own life, which he attributes to the unsettled ghost of his father. Although she has no memory of her teenage years, Winnie readily accepts the challenge of researching Chinese ancestor worship and funeral customs, a subject in which she already takes more than a passing interest. Around the same time she bumps into a former boyfriend and his partner, Karen a psychotherapist, and readily agrees to see them separately for sex without strings.

I wasn’t sure how to take this novel initially. There’s certainly humour in the chaos underlying Winnie’s surface serenity, and I definitely enjoyed the playful take on mindfulness and its current popularity in the West. Perhaps because I identified too much with Winnie’s absorption in the moment (although, unlike her, I don’t forget to eat), it took me a while to find the heart of this story in what the narrator isn’t telling us about herself. When I did, it was immensely satisfying.

After The Clocks in This House, and, of course, as the publishers of Alison Moore, Salt (who provided my review copy) is becoming my go-to publisher for original, ambitious yet accessible fiction that defies classification. Although I’m not sure Marie Gameson manages to connect all the dots she’s laid out in her debut novel, her perspective on memory, difference, death and the enigma of identity, in conjunction with her expertise as a storyteller makes The Giddy Career of Mr Gadd (Deceased) an extremely worthwhile read.

For my own perspective on forgotten schooldays, see my short story, Kinky Norm.

Pseudotooth by Verity Holloway

Mostly because it’s so unlike my usual reading, I did struggle to follow Aisling’s journey the further she ventured from her home. But Verity Holloway’s writing is strong enough to carry along a realist like me and ensure I enjoyed the ride. With, to quote the blurb, themes of “trauma, social difference and our conflicting desires for purity and acceptance, asking questions about those who society shuns, and why”, I think it might appeal particularly to readers of YA. And William Blake. (Although I’m far from a knowledgeable about either.) Thanks to Unsung stories for my review copy.

| I finished reading this novel just in time to link my review to a new 99-word story based on this week’s Carrot Ranch prompt. See what you think of my take on an unexpected landing. |

Like stepping back from a pointillist painting: distance gives sensation shape. On a scale of one to ten not the worst I’ve suffered: I might have wet myself but I’m uninjured, and I’ve come round in my own bed. The room whirls, but only slightly, as I get to my feet.

On the landing, my vision blurs again, the carpet a kaleidoscope of colour. Brushing the wall for balance, I stagger towards the bathroom and a reviving shower. Ouch! My shoulder dislodges a framed photo. That’s not my family staring out of the picture. This isn’t my house.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed