| What do you think has most shaped your identity? Is it the genetic code inherited from your parents? Is it the culture into which you were born? Is it the way you were nurtured or not in infancy? Okay, a single blog post can’t begin to answer those questions but, with an overdue book review, a memoir and flash fiction prompt deadlines looming, I’m set to dip into the terrain. |

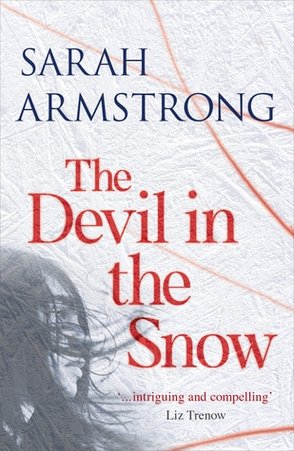

| There isn’t a great deal to envy in Shona’s life right now. Okay, she has a roof over her head, but she shares a bed with her five-year-old and can’t use the downstairs front room because her estranged husband’s locked her out. Okay, she has children but the middle one died, her youngest doesn’t know his father and her teenaged daughter thinks she’s a slag. Okay, she has a wider family but her Uncle Jimmy is a dodgy antiques dealer and her mother thinks she’s cursed by the devil. Add in the interfering friend, the lover who can’t take responsibility and the young man squatting in her shed, who thinks he’s a shaman but might be mentally ill, and we know things are bound to get worse before they can get better. |

Charli Mills has been musing on the origin stories transmitted through cultures, both formal and less so. In The Devil in the Snow, Shona has struggled to shrug off the family curse that has blighted the women in her bloodline. While she recognises the family myth as fantasy, she feels caught in its grip when history repeats itself.

Shona’s mother felt safer when it snowed because then she could see the devil’s footprints. Late April might seem an odd time of year for me to be thinking of snow, but it turns out that, having had none all winter, a few showers are forecast for this week, underlining the difficulty of using the seasonal variations to mark time in fiction.

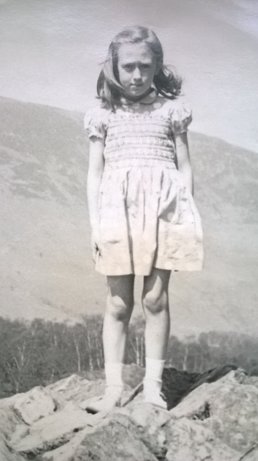

Of course, we Brits are renowned for our addiction to discussing the weather. As a gardener, keen walker and advocate of drying the laundry outside, I’m very alert to the fluctuations in sun, wind and rain. But I hadn’t asked myself when I first noticed the weather as a child until I read Irene Waters’ post for April’s Times Past collective memoir project. Now, while it’s possible I’m influenced by Sarah Armstrong’s novel, I do think my first memory of weather having a significant impact is of snow when I was seven years old.

Snow capped the fells most winters, but it rarely reached our coastal town. So it took everyone by surprise when, by early afternoon, the snow lay deeper than a child’s shoes. When the headmistress closed school early did she think through the logistics, when few families possessed a telephone, of getting the children home?

At seven, I usually walked the two miles there and back with my (reluctant) older brother. But when I waited, and waited a little longer and he hadn’t appeared, some teacher decided I should take the school bus. I recall the shame of having to borrow the penny for the fare.

But it wasn’t for poverty that we didn’t use the bus, it was because the route didn’t pass very close to our house. Not only that, it meandered through a part of town unfamiliar to me, rendered even stranger by the blanket of snow. Wherever it dropped me, I still had quite a hike.

I trudged home to find my brother sitting snug by the fire. He hadn’t walked or taken a (nonexistent) different bus. My dad had clocked off work early to collect us by car. Pity they didn’t wait for me.

I hoped I might be able to squeeze this story into ninety-nine words, but it’s taken (exactly) twice that amount. It’s also reminded me of my aversion to telling a story through memoir (although I did enjoy my memories of Dhaka) – and yet there’s something that compels me to join in! I think this memory from childhood has story potential, especially as it lends itself to different interpretations (childhood resilience versus neglect), but hard for me personally to relate it well. How do you write well about a painful memory? How do you write well when you can’t remember every detail but can’t make things up? (Actually I cheated on the bus fare – I can’t recall how much it cost. And I’ve no idea my brother where my brother was when I got home. See what I mean? How can you not fill in the gaps?) Even though it’s twice the length I wanted, I also find it hard to let this piece stand alone, defensive about both my own interpretation of its meaning as well as the reputation of my dad.

| Some memories are better managed in therapy than on a blog. But some people consider therapy an indulgence (although I’m not sure what’s wrong with an indulgence that has fewer calories than a cream cake and is far better value for money) or narcissistic navel gazing. However, it’s my view that an understanding of one’s own early attachment experiences can help us live effectively, and even happily, in the here and now. Yet, until I read Charli’s post and prompt to write a 99-word navel story, it hadn’t struck me how apt the navel gazing metaphor is for the therapy experience of examining our early years, months or, for some of us, hours. (For another flash on the theme of therapy follow the link.) |

“Where should I start?”

“Wherever you like.”

She blushes, gazes down at herself pointedly. Was it sex? (It’s always sex.)

“There’s no rush. You’ve already taken the most important step by coming here.”

She hesitates. Opens her mouth and closes it again. I’d like to make it easier for her, but she has to find her own way.

She strokes her abdomen. Pregnancy ambivalence? But she isn’t showing. Yet.

Through her thin T-shirt she dips her middle finger into her belly button. “It might sound stupid,” she says, “but I’ve felt all wrong since the day I was born.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed