| I must remember that the responsibility of the female body belongs to me, and that I must not move or walk in such a fashion that makes others feel it is an object of allurement and enjoyment (although I should respectfully tolerate the gropes, the whistles, the hissed invitations); I must learn that a Communist woman is treated equally and respectfully by comrades in public but can be slapped and called a whore behind closed doors. This is dialectics. |

Although there is a plot, with increasing tension as we discover the extremes of degradation to which this man subjects his wife, it’s written as a series of meditations on the theme. Sometimes the author distances both herself and the reader from the narrative, as if viewing it as a film; sometimes she brings us so uncomfortably close it’s almost unbearable. The opening, five years on from the marriage is tinged with comedy, an account that anyone with a narcissistic relative will recognise, as her mother positions herself as central to the drama. Humour turns to horror as we see not only the part that her parents might have played in shaping her personality such that protest is alien, but in keeping her there even when, in the only phone calls she’s allowed, she tells them of her husband’s violence. Only when he’s actively threatened to kill her can they allow her to return home.

Some of this can be attributed to the context of a culture in transition from a traditional structure but, as depicted in The Natural Way of Things, misogyny masquerading as progress, is a worldwide phenomenon. In fact, at the time I was reading this novel I also read an article by Louise Tickle in the Guardian on control and coercion in intimate relationships, prompted by a case in the UK of a woman murdered by her partner.

As my own recently published second novel, Underneath, is also about a man who keeps a woman prisoner in an ordinary house (although my character relies on strong bolts more than threats of violence), I was curious about the husband’s motivation. Like my character, Steve, there’s a denial of his own vulnerabilities, but also an envy of privilege and a rumbling self-hatred, such that he perceives his marriage as a failure in him (p136):

It’s these tiny compromises that erode me. It’s why I’m a married man today, instead of being a militant. I’m a salaried dog, instead of being underground. That’s the petit-bourgeois vacillation that Mao talks about.

As with Steve, the longer the situation continues, the more disturbed and mad he seems, until his paranoia sees him filling keyholes with chewing gum so that the boy who tends the garden can’t spy on them in bed. As for the woman, it’s her hope that things will change for the better that keeps her there, of which she says (p182):

Hope – the cliché goes – is the last thing to disappear. I sometimes wish it had abandoned me first, with no farewell note or goodbye hug, and forced me to act.

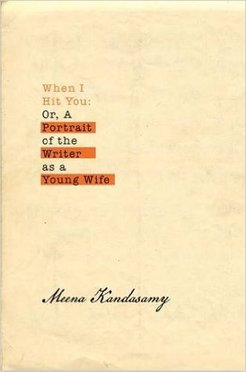

The publisher informs us that the novel is “informed and inspired by her own experiences” but, as I’ve suggested before, having lived an interesting story isn’t necessarily a reason to write about it. Like appearing in court, sharing these stories can be a “second, more sophisticated punishment” (p248). Though painful to read in places, I imagine it being even more painful to write. But in its honesty, its playfulness with form and language, When I Hit You is also an engaging and worthwhile read. Thanks to Atlantic Books for my review copy. If you’re interested in fictional domestic violence, see also my review of Shelter.

| While the experience of marriage as affray leading to a fraying of the writer’s identity in an appalling manner, it’s rather neat for me as a link to this week’s flash fiction challenge. I do like the metaphor of fraying and unravelling and crude attempts to prevent it through excessive control. Although I’ve drawn on it before in my fiction, I thought I’d give this theme another airing: |

She played the pins the way the nuns taught her: in – over – through – off. Later, when her dreams began to fray at the edges, until all she’d worked for seemed to slip away, she added another stage, and another: pull – pull tight.

Her kids complained their clothes were too constraining, biting into their armpits, crushing their chests. They wanted the freedom to flap their arms. They thought, in their youth and innocence, they might fly.

But she was stronger, wiser, resolved to save them the only way she could. Weaving a cage with her yarn to lock them in.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed