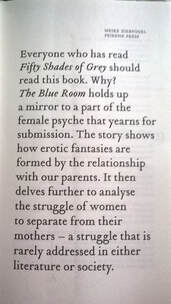

The Blue Room by Hanne Ørstavik translated by

Deborah Dawkin

The novella opens on the morning the young woman is due to depart for America with Ivar, but her mother has left for work and Johanne is locked in her room. As she tries to stay calm, and to puzzle over potential escape strategies, she reflects on her life and her core relationships: with her mother, with Ivar, with her friend Karin, and with God.

The unadorned language suits the story perfectly, with even Johanne’s sadomasochistic fantasies revealed in a matter-of-fact manner. My stomach clenched, however, at the (author’s – or translator’s – who can tell?) repeated misuse of the word stomach for abdomen, especially when Johanne tries to soothe herself with deep breaths.

Although Johanne has high ambitions for her career, she’s right at the beginning of her psychology studies, and I enjoyed her musings over classic experiments, concepts and theories – although I was surprised she was introduced to cognitive dissonance and attribution theory in the same lecture. But this nudges the reader to consider the psychology of Johanne’s character, drawing on these and other constructs. How much of her ties to her mother can be attributed to her own fears of separation versus her mother’s narcissistic need for control? Is the dissonance induced by her sexual awakening conflicting with her desire to please and protect her mother, and symbolised by the locked door, too much to bear? Are her disturbing fantasies of sexual submission rooted in a primary relationship with a parent who perceived her as an extension of herself?

I’d have liked more about her infancy and early childhood to answer those questions fully, and I wondered about the absent father‘s relationship with Johanne, although he seems to have been sexually violent towards his wife. In contrast to when the novella was first published – in Norwegian in 1999, and the mother’s use of a Walkman to listen to music dates the story from around that time – a student staying at home rather than sharing a house with friends wouldn’t be so unusual today. When we come across real-life stories of parents having their adolescent offspring abducted to desert boot camps, locking a bedroom door for the day doesn’t seem so extreme. Especially if your unworldly daughter is planning to miss several weeks of lectures to travel abroad with a man she’s only recently met.

Given Johanne’s naivety, it’s a stroke of good luck she’s fallen for a decent-enough man and that the sex is less brutal than her fantasies; that’s if we can believe her account. I also think that the story could have been more psychologically subtle had there been a certain twist at the end. But, raising lots of questions, it’s perfect for book groups, which is handy because that’s how it came my way. Published by Peirene Press in 2014, I bought my own copy and the lively discussion – including the multiple associations to the blue of the title – brought home to me how much of the nuances my rushed or lazy reading pace meant I’d missed.

| If you’d like to read another coming-of-age story peppered with psychology you might enjoy my own debut novel, Sugar and Snails, about a psychology lecturer who has kept her past identity a secret for thirty years, which was shortlisted for the 2016 Polari First Book Prize. |

“I Want Doesn’t Get” is about a woman whose identity has merged with her mother’s.

The Ha-Ha by Jennifer Dawson

Luckily Josephine finds a friend in Alistair, whom she meets while she’s lying in the ha-ha in the hospital grounds. He makes her feel like a person again after a disastrous outing to a party in the ‘real world’ where her inability to make small talk leaves her feeling isolated and estranged. Unfortunately, Alastair can’t fix everything and has his own mental health issues too. After a brief flowering, Josephine’s back in the dormitory with Judas Iscariot and the rest.

It seems she’s always been odd: her mother at pains to curb her inappropriate giggling, although the pair were the best of friends. Little wonder then that Josephine struggled on leaving home for Oxford University, and more so on her mother’s death. The first-person narration, firmly embedded in Josephine’s unusual mind, does not dwell on these events, however; more on her struggles in conversation, her inability to follow the rules.

Nowadays, Josephine might attract a diagnosis of Asperger’s and – or is this wishful thinking? – might have been helped before she’s developed the need to hallucinate the animals that keep her company and earn her a schizophrenia label. But Alistair advises not to worry about the system’s definitions, the main thing is to be herself.

Like The Faculty of Dreams, the novella provides a rare insight into an unusual mind and the pain of being able to see beneath a veil that others barely notice. Josephine can’t follow the social rules, and sometimes she doesn’t want to. Her dilemma is that she’s happiest cut off from other people, but that’s when she’s deemed most mad.

| I was preparing lunch for my book group when I read Charli’s post with the call for 99-word stories featuring a poisoned apple. No prizes for guessing where that took me … |

There wasn’t much my mother loved, but she sure did love that tree. Sharp shade at summer’s peak; soft pink blossom at its dawn. Come summer’s end she loved to feed its sweet-sour fruit to me.

When time was ripe she’d pick a golden orb and shine its skin with hers. Warmed and polished by her breast, I’d accept her offering solemnly. As if cradling the whole world in my palms.

“Eat!” she said.

Obediently, I crunched, as juices dribbled from my mouth. Although it gave me bellyache, I never once declined an apple from my mother’s poisoned tree.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed