I’m a great fan of Emma Darwin’s posts on writing because, while they’re stuffed with useful advice, she never pretends there’s a simple formula (or two or three or two hundred and three) to make our novels novel and our sentences sing. That’s not the case in some other corners of the creative writing industry. As I’ve mentioned before, I’m particularly hacked off by an implicit assumption that the classic quest underlies each and every story structure: we just have to decide what our hero wants and thwart him in his journey to find it. While I can see how that works for some fiction, lots of the novels I read and love don’t go down that route. On top of that, human motivation is a complex construct: some people genuinely don’t know what they want and some are far too passive to follow their dreams. Some are constrained by circumstances or demons from the past and some characters sabotage their own desires.

Diana is terrified of anyone discovering her past

becomes

Diana is driven to obscure her past

Voila! But I’m still not satisfied. My character’s motivation to avoid seems qualitatively different to another character’s motivation to possess or share or celebrate.

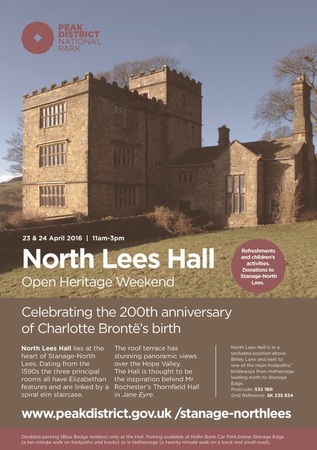

(If you’d like to know more about the area in which Charlotte Brontë was thought to have set Jane Eyre, North Lees Hall is open to the public later this month, and I’m leading a guided walk at the beginning of July.)

Many of my readers also visit Charli Mills over at Carrot Ranch Communications. If you’ve followed her excellent posts for a while, you’ll probably be aware of how keen she is on the quest or hero’s journey. So it might come as a surprise that I discovered (what I’m hoping might be) the solution to my motivation dilemma in one of her posts. When she challenged us to poke a pencil at fear in a 99-word flash, it occurred to me that fear (even when it’s paralysing) can be as strong a spur to action as desire.

The experience of fear is universal and our characters might be driven by fear at one moment and desire at another. But there might also be enduring personality traits that make us more prone to one type of motivator than the other. I’m particularly interested in characters who are driven by this fundamental fear than those who are primarily driven by want.

From my reading of attachment theory (worth revisiting this post on attachment and self-compassion for the illuminating video), it seems that those who grow up with a secure foundation would be more likely to be motivated by desire, while those with insecure attachment patterns would be more motivated by fear. If you can’t trust that the world is generally safe and you can get help when you need it, you’re going to be more heavily invested in minimising threats than in seeking out rewards.

That’s certainly how I perceive Diana in Sugar and Snails, as well as Steve, the antihero of my next novel, Underneath. I think the same applies to Tess Lohan, the main character in Mary Costello’s deeply moving novel, Academy Street (p158-9):

She had been too afraid. She had always been waiting for something to take, for the veils of abstraction to lift and reveal the life that was meant for her.

First aid

They say, in an emergency, the training kicks in. But I’d hoped I’d never need to put it to the test. Yet I pulled over promptly, running through the ABCs in my head.

Fortunately they were conscious, and breathing, and there wasn’t much blood. After making the 999 call, I was calm enough to let work know I’d be late.

Wall-to-wall meetings, the usual stuff. I looked forward to cocktails, scented candles and a warm bath. But, back in the driving seat, I can’t start the car. It’s not the engine that’s stalled but trust the world is safe.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed