While I enjoyed these stories based on real historical figures, with repeated themes of exploitation and exile, adoptees and orphans, and names and details (railways, laundries and sex work in particular) echoing across the decades, it didn’t come together for me as a novel until the contemporary strand. Here, an American writer, John Ling Smith, and his wife, Nola, complete the circle by coming to China to adopt a baby girl. Insomniac, ambivalent about becoming a father and suspicious of the motivations of his fellow adoptive parents, John is disorientated by the experience of looking like the locals but feeling estranged from both their language and outlook. Growing up, he’s felt constrained by a (p226):

list of things you couldn’t do if you were Asian-American: play ping-pong, play piano, wear glasses … wear a camera round your neck, ride a bike, drive an import, grow a moustache (or, if female, streak your hair)

which leaves him with a fragile, even false, sense of self so that, even though he’s in his thirties, his is very much a coming-of-age story.

As the narrative deepens, it’s clear that the evolution of Chinese-American identity is entwined with the evolution of white racism. Perhaps presaging the current sociopolitical climate, in which long dormant attitudes have been reignited, John is sceptical of the (p231):

whole “culture” thing … [as] a defence against racism, an anticipation of it, but also perhaps in some obscure way a perpetuation of it.

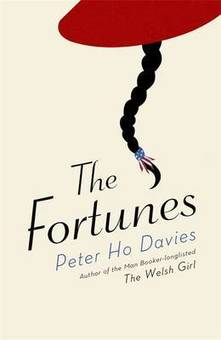

Many novels (including my own debut) explore conflicts of identity, but I found The Fortunes especially strong in showing how it’s forged from an interaction between inside and outside. And, while external forces might impact more strongly on some than on others, we all have a degree of choice over how much we internalise mainstream perceptions of who we are. So thanks Peter Ho Davies for extending my thinking in these areas and, I hope he’ll forgive me for reclaiming my fourth child’s portion of being Chinese.

| By sheer serendipity, I’d started reading this novel the night before I picked up the latest Carrot Ranch flash fiction challenge. The theme of “not allowed” is a perfect fit for a novel about fitting in (or not). I considered staying with the theme of identity but my muse took my 99 words in a different direction: |

From their very first meeting he’d set her spine atingle. Now, as he confessed his desire, her juices pooled in her pants. For weeks she’d suppressed her own yearning, averting her gaze from his groin. Slowly, she rose from her seat and turned the key in the door. Swapping professionalism for passion, she pounced on the couch, and cradled his crotch.

With a sigh, Anne highlighted the paragraph and pressed delete. It wasn’t only the threat of being nominated for the Bad Sex Award. Even in fiction, therapists aren’t allowed to have sex with their clients.

Uncharacteristic of me to interpret the prompt in a positive way but, of course, you can detect my irritation with authors who push their fictional therapists across the boundaries. If there’s any risk of you joining them, you might find a counterargument in my review of In Therapy.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed