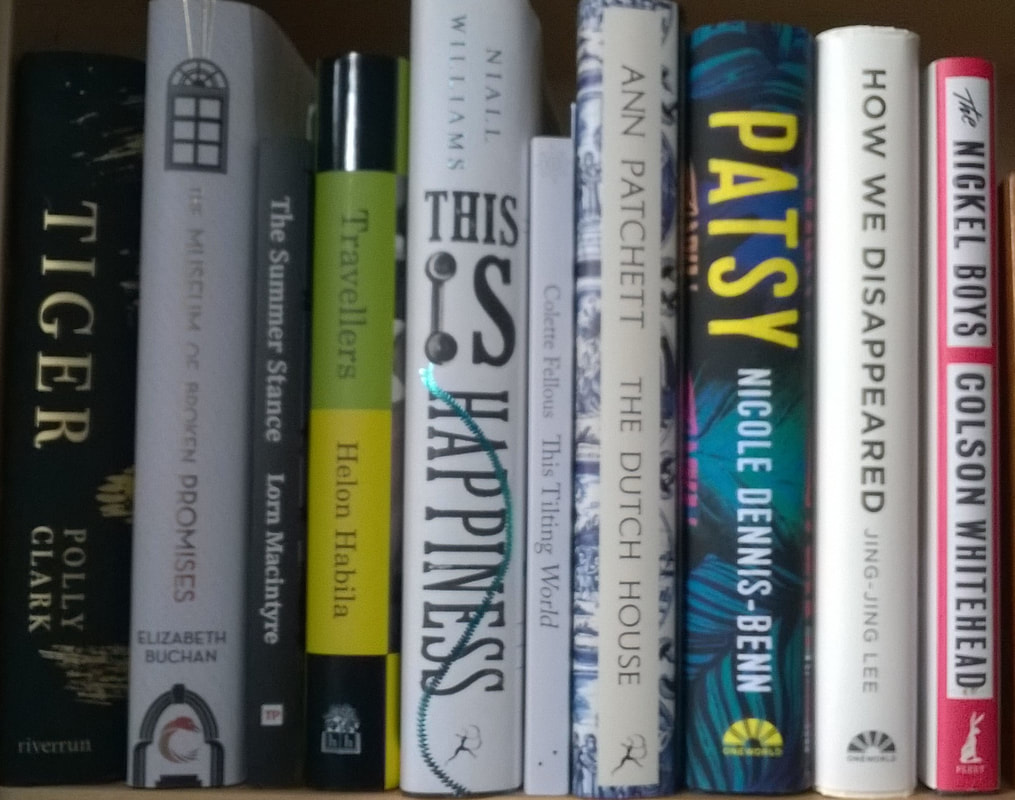

How We Disappeared by Jing-Jing Lee

In the year 2000, and newly widowed, she’s further disorientated by compulsory relocation to an apartment in an unfamiliar district. She’s tried to get to know her neighbours, but they’re suspicious of the odd woman who brings home a cartful of rubbish, a hoarding habit[1] leftover from when she had nothing[2]. Despite a loving marriage she’s barely been able to acknowledge her years as a “comfort woman”, let alone discuss it, partly due to the unspeakable horror, partly because, like many forced into sexual slavery[3], she was blamed on her return.

Not so many miles away, twelve-year-old Kevin is also confused. His grandmother, with whom he shared a bedroom, has been rushed to hospital. Before she dies, mistaking the boy for her son, she makes a startling confession. As his father sinks into depression, Kevin sets aside his fear of bullies, to find out the truth.

Weaving timelines and two point of view characters, there’s a mystery[4] to be solved but, for me, the heart of the novel is Wang Di’s inhumane treatment as a casualty of war. Although unpleasant to contemplate, I could have done with less of Kevin (although I have no problem with his portrayal) and more of Wang Di. That might be partly down to my guilt: although I’d heard of comfort women, I hadn’t given much thought to how they were conscripted into the job. It actually left me quite angry, and wondering about collective denial of the extent to which rape is a weapon of war. Thanks to publishers Oneworld for my review copy.

[1] See my review of The Hoarder with links to a couple of other novels on this theme.

[2] See my post on The aftermath of terror

[3] For a contemporary, and Western, take on this, see my review of The Squeeze

[4] See Unravelling the mystery of mystery for my how-to post on weaving mystery into a novel

The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead

He tries. He leaves home in ample time to hitchhike seven miles to the college south of Tallahassee and a driver’s kind enough to stop and pick him up. When the police pull them over, it turns out the car is stolen. Although the author doesn’t linger on the details, Elwood’s judged guilty by association and the colour of his skin.

Too young for prison, he’s delivered to The Nickel Academy, a segregated reform school in the Florida swamps. It claims to provide intellectual and moral training to transform the inmates into “honourable and honest men” although, run by paedophiles, torturers and Ku Klux Klan members, the staff might need such training more than the kids. Education is minimal, bullying rife and punishment harsh and indiscriminate, with the local community not only turning a blind eye but colluding in, and benefiting from, a trade in supplies intended for the school, and the boys’ labour. While Elwood tries to hold on to Dr King’s teachings, his friend Turner is willing to do whatever it takes to survive.

Inspired[1] by the story of the Dozier School for Boys which ruined lives for over a century[2] and didn’t close until 2011, where bodies have been discovered recently in unmarked graves[3], the corruption provides light relief from the brutality, so this isn’t an easy read[4]. But it’s an important one. I might have numbed myself as, for a while, I didn’t think it was as good as his previous novel, the Pulitzer Prize winning, The Underground Railroad. Then the ending completely blew me away, rendering the novel both sadder and more uplifting in a manner I’d love to share with you but, much more, I want you to discover it for yourself. Definitely one of this year’s favourite reads; thanks to publishers Fleet for my review copy.

[1] If that isn't too positive a term for something so gruesome.

[2] See also my review of Goodhouse, also based on an American reform school.

[3] As there are suspicious graves in the grounds of Irish institutions, fictionalised in He Is Mine and I Have No Other

[4] Although softened by fine writing and being fairly short.

| I’ve written about institutionalised cruelty in my published and unpublished fiction, although – protecting myself or my potential readers? – I shy away from explicitly showing it as much as the authors of these two novels. I even have an unfinished short story about a survivor of a brutal reform school getting revenge on an elderly ex-teacher and my short story collection, Becoming Someone, includes two Holocaust survivor stories and one about refugees from a Middle Eastern dictatorship, among several much lighter pieces. |

| Regarding my longer projects, in my current WIP, Snowflake, the teenage narrator is terrified of the prospect of Bootcamp, an adolescent rite of passage with echoes of reform school that’s guaranteed to turn boys into men, but only if they survive the process. Meanwhile, the heroine of my possibly third novel, Matilda Windsor Is Coming Home, has endured fifty years of psychiatric hospital “care”, treated more like a diagnosis than a person, although she’s great fun when the novel opens in 1989. The protagonist of my debut novel, Sugar and Snails, is anxious enough about her secret past being exposed without me sending to some evil institution, but her father’s experience as a prisoner of war has affected his parenting choices, and hence her character, and adverse ways. |

| So I had a lot to draw on when considering my response to the latest flash fiction challenge. As government becomes progressively more chaotic and shameless, I could’ve gone political, as I did with the prompt true grit. In the end, I married last week’s attachment theme with my current WIP to show the adolescent narrator in a Ceausescu-style nursery: |

What a racket! Unpatriotic to cry while the rest of the nursery slept. Nelson grabbed the traitor from its cot, ready to shake it and scream at it to stop.

The name stamped on the baby’s bib almost made him drop it. The infant was a Nelson too. The revelation brought a yearning that threatened to swallow the pair of them, a hollowness from before memory began.

He wanted to run. He wanted to crush the tiny skull. But he made a cradle of his arms and rocked his namesake. Soothing his unremembered anguish as he lulled the child.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed