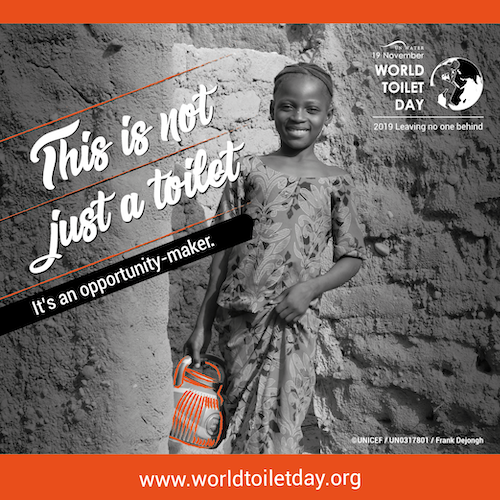

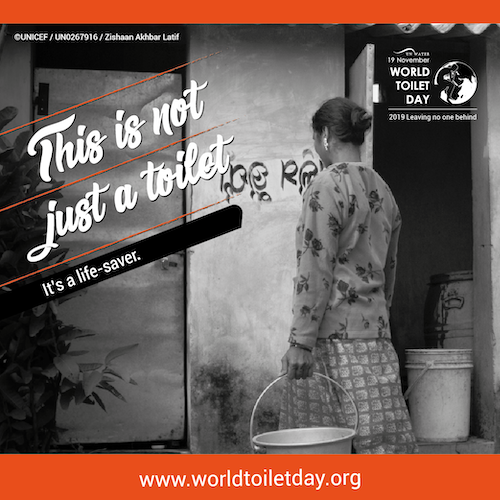

| World Toilet Day on November 19th is an opportunity for those of us fortunate enough to have safe, clean and accessible toilets to put aside our prudishness and acknowledge our gratitude and to support the 4.2 billion people worldwide don’t have this luxury. Apart from last year, when I was wrapped up in preparing for the launch of my short story collection (although even then I gave it a mention), I’ve tried to raise awareness with a relevant post every year since I started blogging in 2013. Since 2016, I’ve been celebrating the novels I’ve read which in some way remind us of our dependence on toilets. Today I’m adding 8 more, bringing my grand total to 18. |

For those of us who can take our toilets for granted, the quotations from these two novels illustrate how lucky we are.

In The Braid by Laetitia Colombani, translated from the French by Louise Rogers Lalaurie and published by Picador, one of the three female point of view characters is an impoverished ‘sweeper’ in India. Here’s how she scrapes a living (p4-5):

Manual scavenging: a coy term that bears little relation to reality. There are other words to describe what Smita does for a living: she collects other people’s shit, removing it bare-handed from the dry latrines, using only a stiff reed brush and a metal scoop, all day long. She was six years old … when her mother took her along for the first time. Watch, then you will do the same. Smita remembers the smell that assaulted her, sharp and violent as a swarm of wasps, and unbearable, bestial stench. She had vomited on the side of the road. You’ll get used to it, her mother said. She had lied.

… And yet the government promised toilets, right across the country. They have not come here … people defecate in the open. The ground is filthy, everywhere: the streams and rivers, the fields, polluted with tons of excrement. Sickness spreads like wildfire. The politicians know it: what people want, before reforms or social equality, are toilets. The right to defecate with dignity. In the villages, many women are forced to wait until nightfall, to go out into the fields, exposing themselves to the risk of attack.

five porcelain bowls were set in a line. The bowls lacked seats and were foully splattered; they had no dividers between them; the stench of blocked pipes and a powerful disinfectant stung the throat; at the far end of the room, a few sheets of stiff, translucent lavatory paper hung from a dilapidated roll

Cross-cultural differences

That’s a world away from the all-singing all-dancing toilets in Japan, as I discovered from my reading of The Pine Islands by Marion Poschmann, translated from the German by Jen Calleja and published by Serpent’s Tail, in which a Japanese student and would-be suicide accompanies a European expert on beards on a journey in the footsteps of the seventeenth century haiku poet Basho.

The toilet apparatus didn’t only offer warm flushing water and a heated toilet seat, it also functioned as a stereo with a wide selection of soundscapes including the sea, rain showers, waterfalls of various heights and babbling brooks, but also tweeting birds, the wind in desolate treetops, storms on the coast, as well as all of Mozart’s violin concertos. The mania with cleanliness in this country had gone so far that they even wanted to flush away filthy noises with water sounds … Don’t the intensified water noises only drastically heighten the feelings of shame?

There were also some books furnished by the Ministry of Heritage. Asma had begun reading some sections headed ‘On Matters of Purity’ but they were too boring and she stopped. They were odd, too – the very specific instructions that she couldn’t figure out, because they appeared to make no sense. For example, that one must do one’s intimate business on a soft surface rather than a hard one so that one’s pee sinks in rather than ricocheting and possibly soiling one’s body. Yet every bathroom she’d ever seen had hard surfaces.

If different cultures have different expectations of toilet etiquette, we can sympathise with the mother of a Kosovan Algerian refugee family in a reception centre in Finland in My Cat Yugoslavia by Pajtim Statovci (p147):

The bathrooms had elevated toilet bowls with dubious-looking stains running down the sides. The greatest shock of all was that Finnish people didn’t wash themselves after doing their business but settled for a piece of toilet paper. Paper! That’s why there were no jugs or bottles of water in the bathrooms. It was the most repulsive thing I’d ever seen. How could they walk after doing their business?

My final three toilets are in a Nazi concentration camp, a jihadi training camp in Afghanistan and a summer residence in Cape Cod:

Luce d’Eramo’s autobiographical novel, Deviation, is a dispassionate account of living with disability and of the fight for survival where toilets are a private meeting place, and the place of retreat for striking workers.

Godsend by John Wray is an even-handed telling of a teenage convert to Islam who, disguised as a boy, travels first to a remote Pakistani madrasa, then to fight across the border in Afghanistan. To hide her female identity, she has to to pee separately from the others. When a small boy notices she doesn’t have a penis, she scares him by implying it was cut off.

In The Narrow Land, by Christine Dwyer Hickey, set in 1950 in Cape Cod, Jo Hopper, a painter less famous and successful than her husband Edward, advances the plot with a trip to the loo at a party (p260):

Finally, it comes trickling out, an insipid little effort and after all that trouble and all those stairs. By the time she gets back down, she’ll probably want to go again. She waits for it to finish dripping into the toilet then wipes herself, rearranges her clothing and slowly washes her hands.

| With a watery prompt – storm windows – for this week’s flash fiction challenge, I thought I’d better come up with a 99-word toilet story. With far more rain around here than many of our waterways can handle, I was tempted towards the dark side but, with World Toilet Day being about building a better world, I’ve gone for a celebration. But I think I prefer my previous effort: Whatever happened to Rose and Storm? |

“Is Grandma sick? She’s been in there for hours.”

“She likes solitude. Peace and quiet from you.”

“She’s remembering the bad old days.”

“She’s enjoying the view.”

“Grey skies and rain-lashed wall?”

Grandma’s told us how it used to be, before drainage and latrines. How the water in the streets rose above her kneecaps but nature couldn’t wait for the floodwaters to subside. No other option than to squat in the field outside amid the neighbours’ floating turds. No wonder she’s happy when in the rainy season, enthroned in her small cubicle, behind the storm window, relishing the view.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed