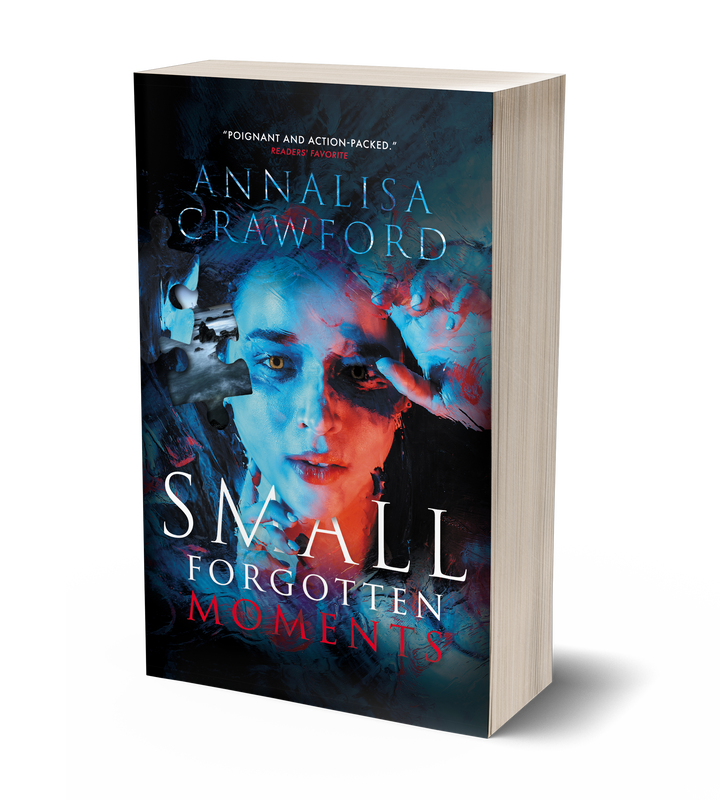

| Annalisa Crawford, author of Grace and Serenity, has a new novel out next month, and she’s kindly agreed to tell us about some of the fiction that inspired Small Forgotten Moments. Two of her chosen four are novels I’ve also read and enjoyed. I’ll hand over to Annalisa to introduce all four. Thanks for inviting me onto your blog today, Anne. I thought I’d share some of the books which have inspired me while writing my new novel Small Forgotten Moments, and the months (even years!) which preceded it. |

Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

|

11 Comments

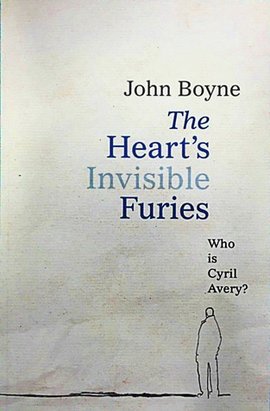

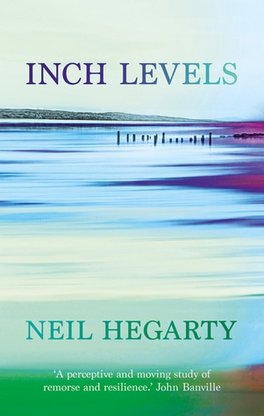

Allow me to introduce you to two novels looking back on Ireland’s recent history through the eyes of a man whose life has been limited by secrets, subterfuge and hypocrisy.

Psychotherapists face a dilemma when it comes to sharing the fruits of their discoveries with a wider public. The technical language, especially regarding psychoanalytic psychotherapy, which practitioners use to communicate between themselves, can be cumbersome, offputting and open to misinterpretation by the uninitiated. Case studies, such as those assembled by Steven Grosz, can be both extremely readable and illuminating, but they do present a problem of confidentiality: even when clients give their consent, some would question whether, within the power dynamics of the relationship, this can ever be freely given yet, the more the details are anonymised, the greater the potential distortion. Susie Orbach is a British psychotherapist, activist and writer who has done much to demystify psychoanalytic thinking (e.g. with several comment pieces in the Guardian, including this recent one on Brexit trauma). Her latest project, on which this short book is based, is a radio series mimicking the experience of the consulting room. After lapping up Anne Tyler’s updated Taming of the Shrew, I was keen to feast my eyes (and brain) on some of the other titles in the Hogarth Shakespeare series. Because the bones of the stories and characters are, to a greater or lesser extent, already familiar, the novels provide a unique insight into the workings on the authors’ imaginations. For the reader, the interpretations highlight the particular passions of our favourite authors. For the writer – especially one like me who continually asks herself How am I going to pull this one off? – they are a lesson in casting the spell that renders the most crazy plots convincing.

While I’d recommend this novel to readers, I want to focus, as I did some time ago with Instructions for a Heatwave, on what we can learn from Laird Hunt’s sixth novel (although the first to be published in the UK) as writers, whether we are looking to write historical fiction or not.

I read for pleasure, for the blog and for lessons in how to write. It’s particularly satisfying when a novel ticks all three boxes, as has happened recently with Maggie O’Farrell’s Instructions for a Heatwave. This is the unputdownable story of what happens to the family of Robert Riordan when he sets out to buy the morning paper and doesn’t come back. It’s the work of an accomplished novelist at the top of her game yet I hope that by peeling back the skin and examining its viscera, I can drag myself a step closer to creating something comparable of my own. The setting Geographically, the novel takes us from North London to New York and Gloucestershire to its climax on a small island in Connemara. While the streets, houses and workplaces are beautifully sketched, it’s the heat and attitudes of the English 1976 summer of drought that defines the setting right from the opening paragraph: The heat, the heat. It wakes Gretta just after dawn, propelling her from the bed and down the stairs. It inhabits the house like a guest who was outstayed his welcome: it lies along corridors, it circles around curtains, it lolls heavily on sofas and chairs. The air in the kitchen is like a solid entity filling the space, pushing Gretta down into the floor, against the side of the table. (p3) Despite Elmore Leonard’s diktat to never open a book with the weather, this setting works by exposing the characters to a situation beyond the everyday: the melting tar, the bands of sweat along the hairline, the unnaturally clear blue skies, the fissures opening up in the lawn provide a back-drop of unease, mirroring the boiling emotions and frayed tempers within the family. The voice Related in the third person from the points of view of Robert’s wife and all three adult children, the voice is elegant without being flashy. It’s not only the heat that feels physically present. Here’s the eldest son, Michael Francis, escaping momentarily from the family home:  Published at the beginning of 2013, The Examined Life by Stephen Grosz is a gem of a book about psychoanalysis. Heavy with insight into the human condition while light on the jargon, it’s a most-read for any thoughtful individual, but I’m here to argue its particular value for readers and writers of fiction. If you like stories, I think you’ll be interested in these, and if you’re engaged in producing your own fiction, there’s as much to learn from these tales from the therapist’s couch as from any creative writing textbook. Here are 7 reasons why: 1. It’s unashamedly upbeat about the power of stories. Many psychoanalytic case studies read like stories, but these are especially exquisite. Beautiful prose, tightly structured, these are moral stories without being moralistic, gentle fables in the manner of Aesop and Kipling that leave us pondering the big questions of how to live. Alongside the stories from the consulting room, there’s an examination of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol and Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener, and ordinary incidents from the author’s life. Without being heavy handed, he leaves us in no doubt as to the centrality of storytelling, that without our stories we are diminished: [O]ur childhoods leave us in stories … we never found a way to voice, because no-one helped us find the words. When we cannot find a way of telling our story, our story tells us – we dream of these stories, we develop symptoms, or we find ourselves acting in ways we don’t understand. (p10)  Citizens, readers and writers, gather round, for I bring you an important update! Alone or with friends and family, in your offices, at your kitchen tables, on the commute to work: boot up your computers, flip open your laptops, wake up your smartphones and focus your attention on The Great Annecdotal Book Review! If you're going to be traumatised by a novel, it must be a good one. If you're going to go to bed, anxious at what monsters your dreams will churn up, let it be on account of a story worthy of the Pulitzer Prize. After nearly 600 pages in the Democratic Republic of North Korea, at least you you can go back to your own life when it's over. Such a pity the same can't be said of the novel's protagonist, the orphan, Jun Do. Or should that be Commander Ga? The book can be read as a love story, a thriller, a dystopian political satire, a heart-warming tale of the endurance of the human spirit or, as Johnson himself has described it, a trauma narrative. Yet, for me, it’s about the wasteland of a world where the individual is divorced from his/her own story and fiction is an instrument of control. It’s not that there are no stories in this imagined North Korea. Like children in nursery school, or the days of single channel TV, everyone must attend to the year’s Best North Korean Story, broadcast into their homes and workplaces through the ever-present loudspeakers. Orphans, the lowest of the low in this society, are taught, through an allegorical story, that their lives have been saved by the eternal love of Kim Jong Il. Even the hardened interrogators can quote of their favourite lines from the moralising movies of the state cinema. Yet these aren’t stories I’d be proud to write, or look forward to settling down to read. In a society where orphans are scapegoated rather than pitied, stories don’t seem to facilitate empathy in those who hear or read them. In a country where creativity is stifled, stories are designed to keep people in their place. Children, weaned on a diet of propaganda, are confused on being told a tale in which nothing is glorified. With little personal autonomy, character is without meaning. Stories don’t reveal a deeper truth, but turn it upside down, yet no-one dares acknowledge the emperor has no clothes: there was only one penalty, the ultimate one, for questioning reality, how a citizen could fall into great jeopardy for simply noticing that realities had changed (p544). Only in Division 42 do officials express any curiosity about individuals, recording accounts of the prisoners’ lives. Before hooking them up to the autopilot that will deliver a pain so vast it obliterates any last vestiges of personality, they transcribe the biographies of those who have fallen foul of the state, not to be read, but as a form of possession: When you have a subject’s biography, there is nothing between the citizen and the state (p239). I can't make up my mind about novels about writers and writing.  On the one hand, it seems a bit of a copout for a writer to make her (or more often his) main character another writer, a way of sidestepping the fact that a year of waiting tables, colourful or arduous as it might be, has little bearing on the working lives most of her readers, constantly updating their CV's. Who cares about the writing life anyway, except for other writers (although I confess that there seem to be enough of us about to make this a big enough market to target)? Despite, through this blog, I'm buying into the current requirement for self-promotion, and I'm sure Shelley Harris was being modest when she protested she was ordinary, generally I believe we writers are less interesting than what we write. |

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed