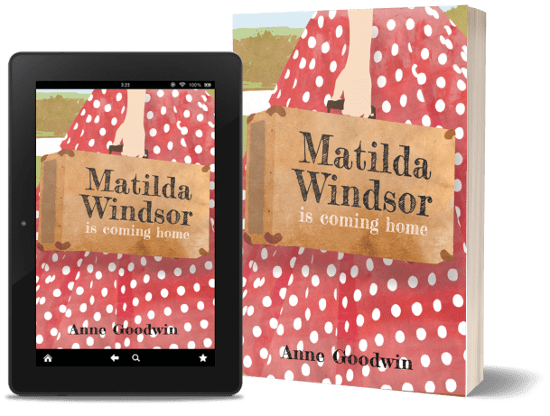

| A black-and-white photograph links two of the three point-of-view characters in my new novel, Matilda Windsor Is Coming Home. In Henry’s interpretation, it shows a father, his glamorous teenage daughter and his young son on holiday at Blackpool, a popular English seaside resort. Matty’s version has a ragged edge and shows only two people: an unknown woman in a polka-dot dress holding the hand of a boy with the Eiffel Tower sprouting from his head. If these two renditions of the same events can be reconciled, perhaps brother and sister will be reunited. Perhaps Matilda Windsor will make it home. |

Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

|

10 Comments

Creative Therapeutic Writing: Fictionalizing the Personal Story (a guest post by Monica Suswin)25/11/2019

The coincidence of Charli Mills’s latest post on the loss of a secure base with the buzz about the bicentenary of Charlotte Brontë’s birth later this month (more on both later in this post) reminded me of this piece on fear as a motivator that has languished in my drafts folder for well over a year. I’m a great fan of Emma Darwin’s posts on writing because, while they’re stuffed with useful advice, she never pretends there’s a simple formula (or two or three or two hundred and three) to make our novels novel and our sentences sing. That’s not the case in some other corners of the creative writing industry. As I’ve mentioned before, I’m particularly hacked off by an implicit assumption that the classic quest underlies each and every story structure: we just have to decide what our hero wants and thwart him in his journey to find it. While I can see how that works for some fiction, lots of the novels I read and love don’t go down that route. On top of that, human motivation is a complex construct: some people genuinely don’t know what they want and some are far too passive to follow their dreams. Some are constrained by circumstances or demons from the past and some characters sabotage their own desires.  Over half a century ago, the social scientist and psychoanalyst, Isabel Menzies Lyth was commissioned to carry out an investigation into why so many promising nursing students were dropping out of training. What she discovered makes edifying reading for anyone using, or employed within, the human services or, indeed, any organisation at all. Despite the best intentions of all the staff, the social systems that had evolved within the hospital were like a spanner in the works, functioning against the primary task of healing the sick. Many highly motivated students, despairing at the impossibility of delivering compassionate care, simply left. Yet this human wastage was built into a system that relied on a high volume of low-paid students to deliver patient care, without having sufficient posts for them to move on to on qualification. Although the work is radically different, I’ve wondered for some time whether there’s a similar redundancy built into the creative writing industry, encouraging the dreams of far more budding writers than there are slots in the publishers’ lists.  Early last week, I was contacted by Emily Furniss, who was the publicist for Roopa Farooki's novel, The Good Children, which sparked a lively discussion here on Annecdotal about obedience. Emily invited me to host a post on writing tips as part of a blog tour she was arranging. Of course I was game; I'd enjoyed hosting Janet Watson writing about her memoir and Tom Vowler's Laws for a Literary Life. The blog tour is an excellent way of discovering new blogs and, because I've got some nominations languishing in the virtual cupboard waiting to be appropriately dispensed, I'm awarding each of the four non-commercial blogs partaking in this tour the honourable title of Versatile Blogger. (Only 6 more nominations to go, then.) Do pop over to their blogs to see whether you agree with me about their versatility. Regarding my role in the current tour, by sheer coincidence, I already knew the writer I'd be hosting: Shelley Weiner helped me excise two superfluous point of view characters from my novel, Sugar and Snails – a painful but necessary amputation. So, without further ado, it's over to Shelley and her tips on writing a powerful short story. (Incidentally, I have no connection with the Faber Academy.)  How do you maintain your readers’ investment in your story, keep them rooting for your characters right through to the end? As Juliet O’Callaghan outlined in a blog post a few months ago, teachers of creative writing tell us it’s all down to motivation. The writer’s task is to clarify right from the start what the protagonist wants and devise credible ways of stopping them from getting it until almost the last page. While I can see how this can create tension, I’ve always had a problem applying this “rule” to my writing. My characters refuse to sum up what they’re aiming for in a neat sound-bite and, if they do, they shoot off in the opposite direction a couple of chapters later. I could try reining them in, but they’d only start complaining that I was the one who invited them to act as if they were as quirky and contradictory as real people. In real life, our goals are often fuzzy, especially regarding the things that matter most, and, even if we think we know what we want, we’re often quite haphazard in the way we try to achieve it. Who can show me how to take my characters along an obstacle course that will satisfy the reader without compromising on the complexity of human motivation? It turns out there are some excellent models in the novels I’ve been reading for my interviews with debut authors.

Let’s start with Alys, Always, the foundation for my latest Q&A with author Harriet Lane. What Frances wants is uncertain at the beginning and is gradually shaped by circumstance. Later, when she develops her plan, the details are withheld from the reader. The tension arises, not from following her along a clear path, but from wondering exactly where she’s heading and how far she’s prepared to go. Here’s what the author told me about this apparent subversion of the motivation ideal: |

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

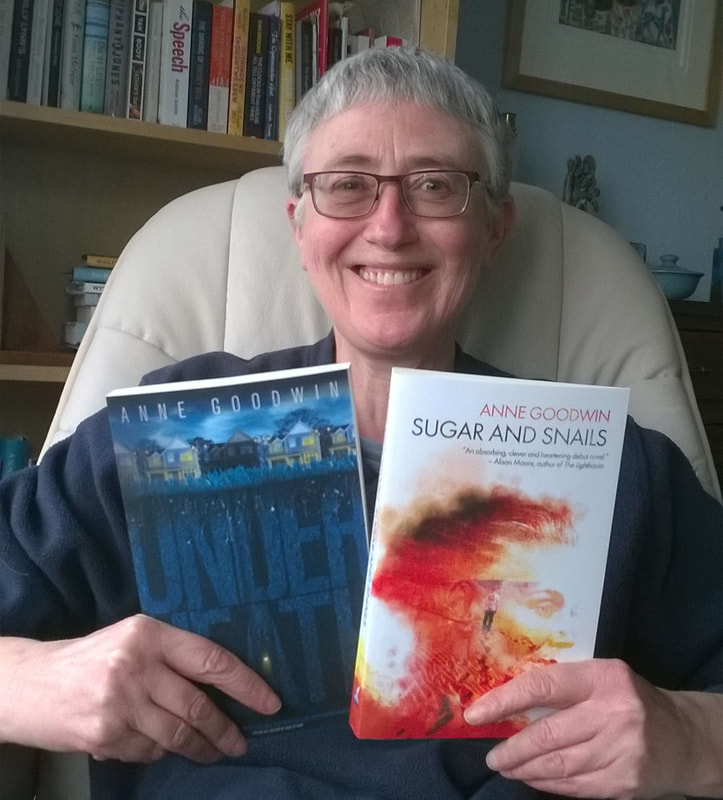

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed