Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

|

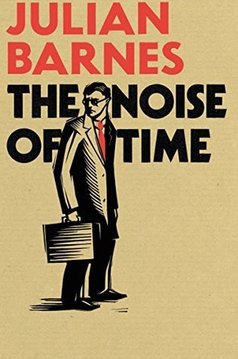

In the week which saw the publication of the results into the inquiry into the killing of Alexander Litvinenko, I read two novels with a Russian connection. Both are about living under the shadow of terror, both penned by lauded English novelists and published in the UK tomorrow. Nevertheless, these are two very different novels; read my reflections to see which you prefer.

12 Comments

I recently shared an extract from my next novel, Underneath, in which a little boy is dancing with his mother to Cliff Richard’s Living Doll. The words are taken all too literally by the child who becomes the man who keeps a woman imprisoned in a cellar but I knew, from the very first draft of this novel, to be wary of quoting song lyrics. Yet, in the version I sent my publisher, I’d retained six words that furnished a neat link between past and present, while demonstrating the narrator’s disturbed and disturbing state of mind. But as publishing becomes a (still fairly distant) reality, I thought I’d better get some advice from the Society of Authors on copyright law. Based on what I was told – and this is only my interpretation – I’ve decided to paraphrase instead of quoting: I don’t want to risk having lawyers on my back; nor do I want to renege on my own personal vow never to pay to be published (it’s the author’s, not the publisher’s, responsibility to seek out and pay for permissions).

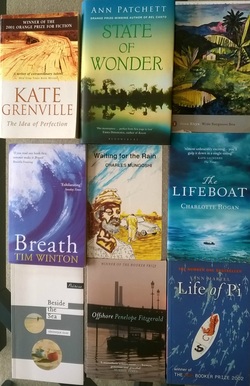

“Sometimes I have trouble finding the edges,” says the narrator, Sean, on page 9 of this unusual and deeply moving debut novel. So far, all I know about him is that he returned from hospital to his parents’ home with painful skin grafts and that, as a young child, obsessed with comic books, he’d imagined himself a throne in his grandparents’ garden, declaring himself King Conan. You’re not the only one, I might have replied. Sharing none of his tastes in TV, music and games, I didn’t hold up much hope of venturing beyond the edges of a novel that spirals round and round its subject but, when I did, I was deeply impressed. While preferring to eschew spoilers, despite the evidence that they are more likely to enhance the reading pleasure than destroy it, I can’t convey my enthusiasm for the novel without wheeling towards its centre, so read on at your own risk.  The war is barely a year old when James is shot down on his first bombing mission. Incarcerated in a POW camp, he vows to use his time productively. Instead of digging escape tunnels from which he’d inevitably be recaptured, James dedicates himself to a detailed study of a pair of redstarts nesting beyond the barbed wire. He records his observations in a notebook and in letters home to his wife. Yet the only person who really seems to understand his passion is the camp commandant. Only six months married before James was summoned to fight for his country, Rose is bored by her husband’s letters, barely able to bring herself to open them, let alone reply. Alone in a tiny cottage on the tip of the Ashdown Forest not far from where she grew up, she spends her time roaming with her dog and patrolling as an ARP warden to safeguard the blackout. She’s wondered about her loneliness for some time: at first she thought it was missing James but now it seems an existential condition. And she’s found a way to soothe it in her secret meetings with Toby, on sick leave from the war. Then James’s elder sister, Enid, is bombed out of her London flat and, with nowhere else to go, she foists herself upon Rose. With her own guilty secret, Enid isn’t the best of houseguests, while Rose is far from the perfect host. The women have more in common than they think, but their different loyalties to James prevents them becoming friends.  Have you ever walked into a room and forgotten what you came for and had to retrace your steps until you know? Have you ever forgotten something you were sure you’d remember and ended up repeating the self-same mistake you’d made the last time? Do you bring back souvenirs from holidays; do you treasure pictures, ornaments and other miscellany, not for their monetary value, but for the memory of how they came your way? Have you ever been touched by music in a place where words hardly signify? Have you ever been affected by a sound so loud you hear it, not just in your ears, but in your entire being? If your answer to any of these questions is yes – and I’d be surprised if it isn’t – you’ll connect with the themes in Anna Smaill’s exceptional debut novel, but you might need to hold onto these ideas to see you through the disorientating opening chapters. The plot is a classic quest: two young men gradually uncover the tangle of lies perpetrated by the elite of their country and set off to infiltrate the seat of power and destroy the source of their destitution, risking their lives in the liberation struggle. It’s a straightforward plot, but deployed with sophistication; there’s no simple demarcation between good and bad. Reaching the hallowed halls, Simon, the narrator wonders (p273): But what did we have to offer her in return, next to this beauty? the voice in my head says. No answers, no order. Nothing but mess, questions, fear.  The daughter of a German concert pianist and her (one-time stand-in page-turner) younger husband, Peggy Hillcoat is eight in the hot summer of 1976 when her father tells her to pack her rucksack and come with him on a journey. As they travel across Europe by car, train and, latterly, on foot, Peggy is less and less confident that this is a holiday. But the stories her father has told her about the secret cabin in the forest spurs her on, and even when she loses her shoe on a perilous river crossing she doesn’t completely give up hope. Yet when they finally reach the cabin, even her father is disappointed at its dilapidated state. Peggy is ready to return home until her father tells her that, not only is her mother dead, but the rest of the world beyond the river is no more. Nine years later, Peggy is back with her mother in London, struggling to adapt to a world of overwhelming luxury and choice (p41):  Young Russian immigrant Slava Gelman’s writerly ambitions stretch far beyond his post among the pondlife at a New York magazine. Following the death of his beloved grandmother, his grandfather commissions him to build upon their sketchy knowledge of her escape from the Minsk ghetto to submit false claims for reparations from the German government on behalf of various inhabitants of “Soviet Brooklyn” who don’t quite fit the strict criteria of experience of ghettos, forced labour and concentration camps. Initially reluctant, Slava discovers in these accounts, not only way to reconnect with his own cultural history, but also the perfect outlet for his literary skills. I was looking forward to reading this novel both for yet another oblique perspective on the second world war and its aftermath and for the sheer audacity of the premise, reminiscent of Shalom Auslander’s fictionalisation of an elderly Anne Frank in Hope: a Tragedy. Unfortunately for me, the novel failed to deliver the promised humour; nor, given that Slava was required to invent the survivor narrative, his grandmother having shared little of her trauma with her family, did I learn as much as I’d hoped. I also found the flashy prose slowed the pace, especially in the first two-thirds of the novel. However, I became more engaged towards the end with the appearance of Otto, German civil servant and amateur sleuth, raising moral questions about whether, and if so under what circumstances, it’s ethical to lie.  It was my wedding anniversary last week and, despite shying away from romantic fiction, I thought I ought to read a novel with a heart at its centre. Thus Jill Dawson’s novel made its way to the top of my TBR pile and, because of its thematic parallels, Rebecca Buck’s novel followed on. Patrick Robson, a history professor with thirty-odd years of over-straining both his literal and metaphorical heart, wakes up in hospital following major surgery with his ex-wife at his bedside. Two hundred years apart, two teenage boys experience their sexual awakening under the wide skies of the Fenlands, and discover how the odds are stacked against those not born into wealth in cash or land. What connects the three main characters is that Drew Beamish was carrying a donor card when he was killed in a motorcycling accident, and Patrick has received his heart, while Willie Beamiss, only just escaping hanging or deportation for rioting, is one of Drew’s ancestors, and commemorated in the local museum. What was that all about, then? After Me Comes the Flood by Sarah Perry and Lucky Us by Amy Bloom4/9/2014  Today I’m reviewing two novels about interpersonal connections that had me struggling to connect with the essence of the story. I’m hoping you can help me untangle why. The opening of Lucky Us seemed promising: My father’s wife died. My mother said we should drive down to his place and see what might be in it for us. She tapped my nose with her grapefruit spoon. “It’s like this,” she said. “Father loves us more, but he’s got another family, a wife, and a girl a little older than you. Her family had all the money. Wipe your face.” Oh, how that mother had me hooked! She seemed much more resourceful in accommodating to the duplicate family than the poor woman I’d left contemplating the cracks in the ceiling in a recent flash. Would the narrator follow her lead? I wondered. Or would she struggle to adapt, like Mary, in Geoff LePard’s novel-in-a-flash? What I didn’t anticipate was that she would abandon both her daughter and the novel only four pages on. Reader, I was bereft. Rudderless, despite, I now discover, having been warned this would happen by the blurb. (But we don’t pay much attention to blurbs, do we?) Eva is twelve when she meets Iris, her father’s other daughter. Over the next decade, we follow their fortunes as Iris seeks stardom in the movies in 1940s America and Eva follows in her slipstream. Through the sisters and their various friends, lovers and hangers on, the novel shows us Hollywood hypocrisy, new-money airs and graces, post-war plastic surgery and the internment camps and repatriation of supposed “enemy aliens”. There are even a few scenes on tarot that had me wondering about extending the criteria for my series on fictional therapists. All very interesting and entertaining, related with that touch of humour evident in the section I’ve quoted above, but I felt rootless, longing, despite my general refusal to bow to the law of motivation, for the narrator to have a little more agency, to come out and tell us what she wants. As Charli Mills says, motivation is movement but movement without motivation is passivity. With the lack of a clear narrative arc, Lucky Us resembled memoir or a truth-based story and, in my mind, that’s not necessarily a compliment. Code makers and code breakers: I Can’t Begin to Tell You by Elizabeth Buchan and a 99-word flash28/8/2014  After my recent posts about obedience to a malign authority and the ensuing atrocities, it’s refreshing to be able to bring you a novel in which people refuse to submit. Even better, in contrast to the stories of women’s subjugation within marriage – wonderful reads as they were – I Can’t Begin to Tell You is a celebration of women’s resistance, courage and determination. Like Simon Mawer’s The Girl Who Fell from the Sky which I read last year, this is a gripping story about the agents and code-breakers of the Special Operations Executive during the Second World War. At its centre is Kay Eberstern, British-born wife of a Danish landowner. Like John Campbell in Johanna Lane’s debut novel, Black Lake, Bror’s attachment to his ancestral lands has led him to go against his wife’s wishes, in this case by signing a declaration of goodwill towards the occupying Nazis. This crack in the marriage widens when Kay is persuaded to provide a refuge for an SOE agent, drawing her into a world of secrets and subterfuge which endangers not only her relationship with Bror, but the entire family. Meanwhile, over in England, Ruby Ingram channels her fury over the fact that, as a woman, she couldn’t be awarded the degree she had earned from Cambridge University, into her efforts to improve the safety of agents in the field.  I’m ambivalent about school. On a personal level, I achieved good outcomes from my long ago schooldays, but this was more by dint of my capacity for obedience than any genuine nurturing of my intellect and creativity. (I’m always pleasantly surprised when children these days claim to enjoy school.) On a political level, the view that mass education can be used to weaken working-class culture sits alongside the genuine enthusiasm for learning I’ve witnessed in places where a school place can’t be taken for granted.  How does this translate into my reading and writing? As a child, I lapped up Enid Blyton’s boarding school stories, although the settings were worlds away from my own experience. The junior equivalent of the country-house genre, St Clare’s, Malory Towers and the like served merely as the backdrop for schoolgirl adventures. And that’s the thing with school stories, the experience is so near universal, it’s difficult to untangle the school aspect from the fact of being a child. When I wrote my bite-size memoir, School at Seven, it was more about friendship betrayed than education. Of my short fiction, school provides the setting for the hormone-heavy story of adolescence, Kinky Norm, and frames the parent-child conflict in both Jessica’s Navel and Elementary Mechanics. The epistolary Bathroom Suite is more about inequality than school refusal.  I’m always suspicious of novels penned by the famous: when the name’s enough to shift the copies off the shelves I’m concerned they won’t have put in their 10,000 hours of apprenticeship to develop the writing craft. It goes against the grain to say it, as I believe we learn better through praise than punishment, but I think we writers need to have been told time after time that our work isn’t good enough before we reach the pinnacle of publication. I have similar feelings about established writers with a lengthy backlist. Sure, they’ve earned their place in those hallowed halls but, with a clutch of literary prizes on the mantelpiece, they don’t have to work so hard to stay there. So why did I pick up (the much lauded Irish writer) Jennifer Johnston’s fifteenth novel? Perhaps it was because I so enjoyed one of her late-ish works, This Is Not a Novel. Perhaps, as I discovered via musician Nick Cave’s wonderful The Death of Bunny Munro, and Peter Matthiessen’s moving final novel, In Paradise, exceptions do exist. A woman returns to her childhood home following the death of a parent and, in the process, discovers some painful truths about her family which impact on how she perceives herself. If fiction thrives on strong emotion and conflict, Carys Bray’s debut novel, about what happens to a Mormon family after their youngest member dies, has all the right ingredients. Grief, while painful to experience, is a powerful launching pad for fiction and, as Derbhile Dromey commented in response to my post on religion and the right to die debate, religion channels conflict in believer and unbeliever alike. Review of A Song For Issy Bradley While four-year-old Issy Bradley is languishing in bed with undiagnosed meningitis, her mother, Claire, is shopping in Asda for affordable party food. Issy’s father, Ian, bishop of the local congregation, is out doing good works for the community and her big sister, Zippy, is lost in Jane Austen’s Persuasion. Of her two brothers, seven-year-old Jacob, is swallowing his disappointment that his dad won’t be able to attend his birthday party and teenager Alma is looking for an escape route so he can go off and play football. When Issy dies, the family’s religious faith proves to be both a source of consolation and pain. The future focus, with the belief that the family will be reunited in eternity, is reassuring for Ian, as he keeps up his church duties, unaware of how much he is neglecting his family and exhausting himself. Claire, who, unlike the other Bradleys, did not grow up as a Mormon but converted when she met Ian, has always found comfort in the sense of order and obedience to a higher power, now feels deserted by God: The country house meets friendship betrayed: The Long Shadow by Mark Mills, with fruit for afters27/7/2014  Who says fiction doesn’t change lives? Thanks to Mark Mills, I’ve learnt how to peel bananas from the bottom end, like a monkey. Not that this is a novel about fruit, or animal behaviour (unless you think young boys are like monkeys), but I was grateful for the tip about bananas at a point when the narrative pace seemed to drag. Ben is a scriptwriter aeons away from the big time, a divorced father living in a grotty flat. When a wealthy former schoolmate offers to bankroll his film and install him in his mansion while he does a rewrite, it seems almost too good to be true. As, indeed, it is, but Ben is so seduced by his good fortune and Victor so skilled at manipulation, it takes some time for him to figure out exactly how and why. When he does, it’s immensely satisfying: country house meets poisonous friendship (and so refreshing to have the latter portrayed from the male point of view for a change) seasoned with boys’ games along the lines of Lord of the Flies, the resolution encompasses envy, childhood neglect, rivalry and turning a blind eye to painful truths in a psychologically astute way. I must confess, however, I appreciated this more in retrospect and there were moments across the first 200 pages when I was tempted to give up.  I had an encouraging response to the musical link I included in my recent post on water-themed fiction. I used to provide a musical accompaniment to my posts quite frequently – up until the beginning of this year I was actively populating my Google+ page with a YouTube link to each blog post – but somehow I'd lost the habit. The latest flash fiction challenge from Charli Mills seems a timely reminder to re-establish the link between music and words. I’ve published a couple of short stories on a musical theme: there’s my flash Getting It Together with Elvis; my short stories Melanie’s Last Tune about a narcissistic music teacher and The Invention of Harmony about a mediaeval nun’s fear of her own creativity. So it didn’t take me long to come up with an idea for the required 99 words. I’m pairing this with the march from Prokofiev’s Love for Three Oranges, although anything that sparks different reactions would do:  The latest flash fiction challenge from Charli Mills sent me cruising my geographically-arranged bookshelves for novels on the theme of water. Waiting for the Rain by Zimbabwean Charles Mungoshi was my obvious starting point since, as usual at this time of year, my garden is particularly thirsty. I try to conserve water by harvesting rain from the drainpipes and pounding my plot with a watering can as the sun goes down behind the trees. But, with my tendency to precrastinate over arduous tasks, I can often make extra work for myself by transplanting seedlings in the heat of the day, then bemoaning their failure to thrive. Yet, through this, through the dirt under my fingernails, I feel a connection to those subsistence farmers whose very survival is dependent on the rain. Of course, there’s an over romanticism bordering on the delusional in this assumed affinity between my pampered life and theirs. The Westerners’ illusions about the poor is one of the themes of Ann Patchett’s novel, State of Wonder, about secret research in the muddy waters of the Brazilian jungle. It’s not too much of a boat ride from the Amazon basin to the West Indies, the setting for Jean Rhys’s reimagining of Charlotte Brontë’s mad-woman-in-the-attic, The Wide Sargasso Sea. Depending on how far they’ve drifted off course, we might also encounter Grace Winter on those waters, fighting for survival in Charlotte Rogan’s debut novel, The Lifeboat. From there, we could sail through the Panama Canal into the Pacific ocean, where, in Yan Martel’s debut, The Life of Pi, a young man shares his lifeboat with a hyena, a zebra, an orangutan and a 450-pound Bengal tiger.  Whenever the interviewees in my debut author Q&A’s complimented me on my questions, I assumed they were merely being polite. Well, they may well have been, but that hasn’t stopped me musing on what constitutes a good question since beginning to tackle the questions set by Norah Colvin for her Liebster Award nominees. How do you define a good question? Despite a fair amount of experience of interviewing – as an element of both selection and therapy – in my other life, I find myself having to rethink the matter all over again for my blogging persona, Annecdotist. From the perspective of a candidate in a job interview, a good question might be the one for which you’ve already prepared a good answer, one that enables you to showcase your skills and talents to good effect. But an interviewer who is genuinely curious is unlikely to be satisfied with a “here’s one I prepared earlier” response. Yes, we shouldn’t be looking to trip up the interviewee, but the interaction will feel more authentic if we are able to create something new in the space between us. So a good question can also be one that takes us by surprise. One of the things I like about Norah’s questions is how well they reflect (what I know of her and) her interests, her passion for learning most of all. This also made them quite difficult to answer: although obsessed with my own thoughts, none of these are the questions that I routinely ask of myself. So I needed to give myself time to consider my responses, to do justice to the spirit in which the questions were asked. Hence the interval between receiving the award and posting my answers. So here are Norah’s questions along with my responses in italics. I’d love to know what you think.  I hadn’t known of this book until I won it in a goodreads giveaway, but what a wonderful freebie it turned out to be. Not only did I find the most endearing alcoholic narrator it’s ever been my pleasure to meet, but another flawed therapist for this series. Peter Newbold is a psychiatrist. As Salley Vickers makes clear in The Other Side of You, this doesn’t automatically qualify him to practice therapy. I don’t know if Dr Newbold has had the requisite additional training – he’s published a book on attachment issues, so clearly knows about a bit more than diagnosis and drugs – but, if he has, it’s not enough to prevent him blurring the boundaries between his professional and personal lives. I’d like to be able to tell you that his behaviour is unbelievable, but sadly some psychiatrists do feel entitled to play by their own rules, even nice chaps like Peter. We see Dr Newbold through the eyes of the narrator, Hildy Good; not a patient, but the estate agent from whom he rents his office. Perhaps through having known him as a child, perhaps through her own mistrust of experts on the psyche, Hildy is far from in awe of his profession: I can walk through a house once and know more about its occupants than a psychiatrist could after a year of sessions. (p1) In some respects, her own intuition, honed through a party-piece she learned from a “clairvoyant” relative, is more accurate than Peter’s, except, perhaps, as regards her own problems, and, in the final analysis, where it really is a matter of life or death.

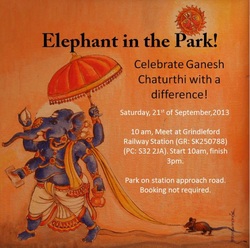

The Good House offers the reader a fairly low-key version of a therapist: Dr Newbold is only one of a wide cast of vulnerable characters muddling through as best they can. Just like real life. For another perspective on this novel, do pop across to A Life in Books. For the next post in this series I’ll be commenting on Therapy by David Lodge. This being my 99th blog post, I'm delighted to be able to bring something a bit special for my centenary: I'll be answering the questions set for me by Norah Colvin as part of the Liebster award. I’d welcome your feedback and, in the meantime, let’s have some 'house' music from Talking Heads.  With another choral concert in the offing, I’ve been conscious recently of my far-from-perfect pitch. Alas, it’s not just musically I’m challenged, but I’ve been struggling with pitching my fiction since an agent workshop around eighteen months ago when I failed dismally to reduce my oeuvre to three sentences, despite my novel being in a not-at-all-desperate state of health. Although I’ve improved dramatically since then, I still find pitching difficult and I’m reassured when bloggers such as Clare O’Dea confirm I’m not alone in this. We don’t all possess the talents of Fay Weldon, coining and promoting advertising slogans like Go to work on an egg alongside writing literary fiction but, in this highly commercialised era, it’s incumbent on writers to try. While a pitch to publishers and agents is not the same as a blurb, and both are distinct from a 140-character enticement to click on the link to a blog post, I’ve learnt a bit on pitching from observing how others market their work on Twitter. It takes a lot of discipline and focus to whittle down the gist of one’s outpourings into a few captivating words. But the ideal pitch isn’t solely down to the writer’s capacity to précis. I don’t think I’m making excuses when I say that some fiction is easier to pitch than others. In an effort to convince you this isn’t only me being precious about my own stuff, I’ll illustrate this but by comparing my Twitter pitches for two of the stories I especially enjoyed from a recent anthology in which my story “A House for the Wazungu” also appears. I’m interested in your views, but I think my first pitch:  Are you sitting comfortably? Then I’ll begin my story of how I helped bring an Indian elephant into the English countryside and learnt something about storytelling in the process. Once upon a time Chamu told me about a guided walk she was planning in the Peak District. The aim was to use story to promote diversity within the national park and the walk would be integrated with the local celebrations for birthday of the Hindu god, Ganesh. Well, I thought, what could be better than walking and storytelling? I jumped at the chance to help out. Although I knew a little about the elephant-headed god from my travels in India many moons ago, these weren’t exactly stories I’d heard my mother’s knee. What if others were more familiar with the story than I was? Would I be able to engage people? What if I forgot my lines? Of course, I needn’t have worried. Thanks to Chamu’s support and a lovely group of tolerant walkers, I had a fabulous time telling my two stories, as you’ll see from the pictures below, and from others on the Hindu Samaj website. The experience got me thinking about the differences between story writing and storytelling. Although I often read my fiction aloud to check for stumbling blocks, telling a story without a script to an audience is another matter altogether. As a reader and as a writer, I treat adverbs with suspicion and every adjective has to earn its keep. Yet the oral form has a baroque feel to it, bustling with verbal curlicues, never using one word when half a dozen will do. Repetition, cliches, It came to pass and In due course – I welcomed them as joyfully as I attempt to edit out each just and quite from the written form. It wasn’t the presence of two delightful children that made me spout such archaic and nursery-style phrases; they seemed appropriate for the story to flow.  Relaxing into the role, I began to tell the story physically: modulating my voice; exaggerating my facial expressions; making judicious use of pauses. I don’t have an extroverted bone in my body, but I couldn’t help falling into the rhythms and performing. This will be no surprise to those familiar with reading bedtime stories, but to me it was a revelation, and I’m looking forward to doing it again at the end of August next year, only better. (If you watch the video below, you'll see there's lots of room for improvement.) If you'd like to come, the details will be on the Ranger walks calendar. If you've been paying attention, you might have noticed I've delivered all the posts I promised for October (gold stars all round). For next month I hope to bring you the fourth instalment in my series on fictional psychologists and psychotherapists; a look at internal obstacles to achieving one's personal and fictional goals inspired by my Q&A with Anthea Nicholson, as well as my recent post on character motivation; and why I'm raving about a small book of psychoanalytic case studies. I've also got posts in the pipeline on writers' routines; writing in the first person plural; old-age stereotypes; leaving home; another look at rhythm and my love affair with allotments. Hopefully there's something you'll want to come back for. If you're still wondering how the elephant god got his head, you can read a précis of the story here:

The video picks up the story halfway through, when Shiva has chopped off the head of Parvati's darling boy and is sending out his bodyguards to find a replacement. Or go here for a musical version of the story.

Reviewing my latest interview with a debut novelist, I’m wondering how come I keep selecting novels where the protagonist goes hungry. Is this about my drive to connect writing with my garden produce, or the authors’ own obsession with food? As I tuck in five-year-old Pea alongside twelve-year-old Haoua, I’m hoping the grown-up protagonists of the other novels, like the anxious but hands-off adults in The Night Rainbow, will offer her something to eat. Yet, somehow, I don't think Futh will notice that Pea’s mother’s forgotten to feed her, and I’m really not sure how patient Grace would be with small children, but perhaps Satish could get his mother to rustle up some party food. I’ve read some of Pea’s interesting thoughts on food, but does she like chakli? I suppose he’d be willing to try anything, as long as Margot goes first. Nutrition isn’t only a biological necessity; in life, as in novels, food symbolises care, and so fiddling around with it serves to make life harder for the protagonists. Writers sacrifice the desires of their characters in favour of the reader’s love of narrative tension. On one level, the thwarting of even imaginary people seems harsh, yet one of the things that struck me across the five Q&A’s I’ve completed so far was the authors’ empathy for their creations. Claire King told me she loved the way I could make myself feel emotions with fiction I had written myself and, over on The Literary Sofa, she highlighted one consequence of writing from a child’s point of view as the need for plenty of tissues. Shelley Harris was so wrapped up in her character’s psyche that she chose

his career unconsciously, as he would have done himself. The impetus for Gavin Weston’s novel was his concern about the fate of a girl his family had sponsored; its completion has driven him to take a more active role in relation to the practice of child marriage by becoming an ambassador for FORWARD. While we might expect writers to empathise with their child characters and/or those who have been treated unjustly, their empathy for their more prickly protagonists was also apparent:  As they crouch to catch the babe, I wonder what might soothe their minds. I don't mean the medical team in the delivery room, but the anxious hacks hovering outside. After the lambasting of Hilary Mantel, it takes guts to say anything intelligent on the royal process, but there was good sense in the other Saturday's Guardian from Marina Hyde. If that's not enough to shame them into leaving the poor woman to get on with the job, the hospital could pipe out the glories of Handel, or read them Kate Blackadder's beautiful story, Oldshoremore from The Back of The Beyond.  In my early days of blogging, I took the 0 Comments by-line at the top of so many posts as an indictment my writing skills. I needed more than the spikes on the website stats chart to convince me I had any readers at all. Six months on I'm happy for you to use the site in any way you like as long as it's legal and decent, but still a little puzzled that so few of you seem to want to leave your mark. Are you all fans of detective fiction, donning kid gloves to come visiting, or has that great poet Leonard Cohen convinced you that true love leaves no traces? That's all well and good, but I can't help wondering if you might enjoy the blog more if it were interactive. A few words for the hesitant. The system asks for your email address: this is standard practice, presumably to deter trolls, and is never published or used to plague you with junk mail, so please don't let that put you off commenting. For those more familiar with fancier systems that let you leave a thumbnail photo along with your comment, I'm sorry weebly is a bit Amish in that regard, but you could always keep it sparkly by linking to your gratavar if you have one. Sometimes it looks as if you can't post a comment after I've done so, but trust the technology, you can. And however elderly the post, or seemingly mundane your views, I'd be pleased to hear from you. Overloading me with comments in response to a post on the shortage of the same would be a neat test of the popular misuse of the word irony, don't you think? I welcome your feedback, or lack of it.  With Grace Winter, heroine of The Lifeboat, now on board the author interview section of annethology, I'm wondering how to introduce her to the two characters already there: Satish and Futh. She's certainly got food issues in common with both of them but, having survived for a couple of weeks on raw fish and hardtack, I imagine that's not something she'd be keen to discuss. The power of memory, and questions of its validity, is an issue explored in all three novels, but, fascinating as it is, I've blogged about memory already, so I've decided to celebrate my third author interview with a quick look at some of the ways these writers have made things harder for their heroes and heroines. This is especially useful for me, as it's something I find quite difficult: I've no problem with bleak, I just don't like making it bleaker. So let's have a look at how Alison Moore, Shelley Harris and Charlotte Rogan have gone about it. 1. Send them on a journey. This can be a journey through geographical space, such as Grace's trip across the Atlantic, or a metaphorical journey back to the past, as Satish faces with the Jubilee party reunion. Or it can be both, as for Futh, with a walking tour that recreates an earlier holiday with his father. Not only is your character stepping out into unfamiliar territory without their familiar props, but there's so much potential for things to go wrong. While most luxury ocean liners don't have to be abandoned, lots of us have had the experience of getting lost and arriving at our destination much later than we'd hoped, or being mentally dragged back to a place in our lives we'd rather leave behind. 2. Foist other people on them. We all know that every protagonist needs an antagonist, someone to thwart their story goals. But they don't need to be much of a villain to make life difficult, they can just be other people being themselves. When Satish's childhood friend pushes him to attend the Jubilee reunion, she can't possibly understand the trauma she's rekindling. Okay, the proprietor of the guesthouse where Futh begins and ends his circular walk isn't a bundle of laughs, but he isn't to know that Futh doesn't understand how other people's minds work and has no idea of the suspicion his behaviour, in all innocence, is arousing. Grace, on the other hand, perhaps stemming from a lifetime of economic dependence in the days before women had the vote, never in my opinion completely loses control, despite relying for her very survival first on her new husband, then on the shifting power dynamics within the lifeboat, and finally on the opinion of the jury about the part she played in the murder of Mr Hardie. The much quoted truism that we can't live with other people and can't live without them either applies as much to novels as to real life. 3. Get down to basics. You know about Maslow's hierarchy, and our basic human need to address our fundamental physiological concerns before we can move on to higher-order issues. I've already mentioned how getting enough, or the right, food had me worried across all three novels, especially The Lifeboat where Grace was at genuine risk of starvation. This was also one of those rare novels where the characters get to go to the toilet – or not, as it happens, given that lifeboats aren't provided with such luxuries, so the poor women had to fiddle about with a bailer under their ankle-length skirts. Not exactly life-threatening, but I do know from experience it's extremely painful, so I did sympathise with Futh and his blisters, while cursing him for buying new walking boots before setting out on a long-distance walk, and I'm not sure that I could have done that to him. Still, the Beatles got it wrong about Jude: it's not the author's job to make it better, we've got to take a sad situation and make it worse. Or at least until the very end of the story. Please share your views on this or any other aspects of the author interviews. The next one, with Gavin Weston, author of Harmattan, should be launched fairly soon, with a post about the end of childhood following on not long after. As for my own writing, June is shaping up to be my personal short story month, with several publications promised: one I've been waiting for for about a year (the contract's signed but I'm not holding my breath) while another two were only accepted this week. I'll keep you informed. |

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed