| It was why they were here, she understood now. For the hatred of what came out of you, what you contained. What you are capable of. She understood because she shared it, this dull fear and hatred of her body. It had bloomed inside her all her life, purged but really growing, unstoppable, every month: this dark weed on the understanding that she was meat, was born to make meat. |

Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

|

4 Comments

The protagonists of novels are often called upon to act more heroically than they might have to in real life. So it can be refreshing to come across main characters who are as ordinary as the rest of us. Here I’m reviewing two novels about the loves and limitations of middle-aged men; the first in America and the second in the UK. Do these characters have enough oomph to keep our interest? Read on for my personal view. (And, for another take on masculinity and compromised morality, see my review of The Faithful Couple.)

With the echos of each other in the titles, I couldn’t resist pairing these two novels published this month, both involving parallel narratives. As I’m playing with a similar structure in my current WIP, I’m also interested in what these novels can teach us about a form that’s more difficult to pull off than we might think.

Identity and make-believe: The Diver’s Clothes Lie Empty & The Life and Death of Sophie Stark4/2/2016 Lately, I’ve been contemplating my identity as a novelist: how, on the one hand, it’s a simple statement of fact while, on the other, it represents an existential anxiety about what I’d be if I couldn’t describe myself in terms of something that sounds like a job. So these two novels exploring identity and make-believe, albeit with reference to film rather than fiction, have come along at exactly the right time.

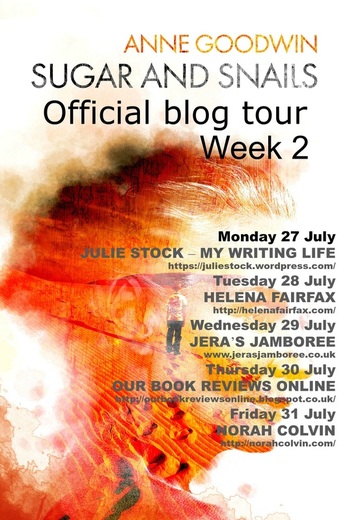

In Gangtok in the remote state of Sikkim, Chitralekha, Nepali-speaking Indian clothing factory owner with the ear of the local politicians, awaits her eighty-fourth birthday. Reluctantly, her thirty-something grandchildren travel from across the world to join her: Agastaya from New York; Manasa from London; and Bhagwati from Boulder, Colorado. Each arrives without their significant other: Agastaya because he can’t tell his family he’s gay; Manasa – married by arrangement into a high-caste Nepali family whose Oxford degree is useless now she stays at home nursing her father-in-law – because she is grateful for a break; Bhagwati because her low-caste Bhutanese husband and two Americanised sons would be unwelcome in the family home. So far, so clichéd, but a dysfunctional family, especially one in an exotic culture, can be entertaining in its way, even if, like in a stale sitcom, the characters are obliged to continually repeat their defining grievances, just in case the audience hasn’t got it.  Francine is grappling bulimia and the menopause along with wondering whether she’ll survive the coming cuts in Quality Assurance. Robin genuinely cares about his students as he philosophises over film and the dread of having a baby with the wrong woman. Olivia wants to put the world to rights but isn’t sure if her law degree will let her, or whether she should start with her own dysfunctional family and the father who’s been hidden from her since she was four. Ed soothes his own loneliness by ensuring the unloved and unwanted still get a good sendoff. Katrin navigates the gulf between London and her native Gdansk in the cafe where she works and with the gentle Englishman who seems to like. Each of these five point of view characters are vividly and sympathetically realised on the page. Each of them follows an interesting narrative arc, complete with back story and associated minor characters, I could have followed for an entire novel. But just as the characters seem to question whether there’s anything more cohesive than the fragments of their world (p151, 267):  If I was breathless last Monday, announcing Week 1 of the Sugar and Snails blog tour, I must be on the verge of a swoon this week as I begin another round of visits. The first week has gone brilliantly (you can catch up with those first five posts via the links on my blog tour page), so how could I not be excited about the second? I start today under Julie Stock’s Author Spotlight, with a piece about setting part of my novel in Cairo. As a writer of contemporary romance from around the world, Julie has a particular interest in the challenges of setting fiction in real places, the subject of her own post on Susanna Bavin’s blog this week. Tomorrow, Helena Fairfax is interviewing me about where my own life is set, among other things. Helen lives in an interesting place herself, the UNESCO World Heritage Site and former mill town, Saltaire, which you can discover more about in her fascinating post. Then I’m off to chat with my namesake, Shaz Goodwin on Jera’s Jamboree. With her day job as a school Inclusion Lead, I was interested in her interest in novels that tackle a social barrier, as Sugar and Snails most definitely does. On Thursday, I’m on Our Book Reviews discussing the various transformations of my novel from its initial inception as a story of masculinity across three generations. This post arose out of a Twitter conversation after Mary, one half of Our Book Reviews, read and reviewed an advance copy. Obviously, I was delighted to be invited back. Finally, Friday sees me in Australia, quite fittingly discussing the theme of friendship in the novel and in its realisation (extending the theme of my previous post on gratitude) with one of my dearest blogging friends, Norah Colvin. As Norah has already hosted me once before, I know the tour bus will be safe to leave there over the weekend until I get behind the wheel again on Monday.  I’m generally not in favour of “update” posts, but I can’t ignore the perspective shift since I posted five days ago. As of last Thursday, I’m a published novelist, and enjoying it immensely. With each review (six to my knowledge so far), with each supportive tweet at #SugarandSnails, I’m claiming more of my authorial authority. I’m even infiltrating the more traditional media, with a feature on Sugar and Snails in the Lincolnshire Echo and a nerve-wracking but not too dreadful outing on BBC Radio Nottingham (my bit is at about 2.15 p.m. and the link expires in about three weeks). The highlight of the last few days was, of course, my Nottingham launch party, which I’ll be sharing more about in due course. But in the meantime, there’s this lovely and unexpected post on the event from The Mole, the other half of Our Book Reviews.  I’m featuring two award-winning short debut novels in translation, the first from Algeria and the second from Brazil, both published in the UK today, that would appeal to those who enjoy philosophical fiction. An elderly man, weary with life, sits in a bar in Oran telling a stranger how the random murder of his brother seventy years before has rendered him an outsider in his own country. Only seven when Musa was killed, his mother’s grief made her neglectful of his needs, binding him to her side and making him the object of her revenge. Spurned by his neighbours for his failure to join the resistance in the 1950s fight for Algerian independence, he’s now aghast at what his country’s become, especially the surge in religiosity (p65-66): As far as I’m concerned, religion is public transportation I never use. This God – I like travelling in his direction, on foot if necessary, but I don’t want to take an organised trip.  On the night after Christmas, a middle-aged woman picks up her pen to write a letter to her estranged friend, Nina, without knowing where she might be or even whether she is alive or dead. Although they have had no contact for more than a decade, the pair have been friends since childhood and, for a few years shared a house as adults along with the narrator’s husband, Nicholas, and Teddy, their young son. Ironically, the narrator addresses her erstwhile friend by the name Teddy assigned to her on their first meeting, although as the novel progresses, its accuracy becomes more apparent (p158) Butterfly: settling on nothing, at the window pane basking or trying to get out, batting at the light as if baffled by this lovely form that is (so it thinks) some fragile decoration of its ugliness.  One of the literary agents who declined my request for representation did so on the basis that she didn’t like the first-person present-tense narration with which my novel opens. While I respected her capacity for clarity about her personal preferences, it did make me wonder about the plethora of good literature she was denying herself, not so much from wannabe novelists like me, but heavyweights like Nick Hornby and Margaret Atwood. I was reminded of this when I came across the concept of the “stolen head” novel in a review by Toby Litt in last Saturday’s Guardian, defined as a novel voiced on behalf of a person (for example, Holden Caulfield of The Catcher in the Rye) who the reader knows wouldn’t have the patience or self-discipline to write the structured, perfectly punctuated prose with which they are credited. The real writer has stolen the life experiences, the sensual perceptions, the vocabulary, of someone beneath or beyond the day-to-day deskishness of writing. Stolen head books are great for giving us very young, very angry or very damaged-first person narrators.  Choosing a second person narrator is a risky decision. Done badly, it makes for an irritating read and, even done well, it’s not everyone’s cup of tea. Although I think it’s handled beautifully in Ewan Morrison’s recent novel Close Your Eyes, a ‘you’ narrator is generally confined to the short story where a degree of experimentation is often more welcome. There are around twenty second-person short stories and pieces of flash fiction in the anthology You, Me & A Bit of We. Seeing them together, if not quite reading them back-to-back, it’s striking how many different interpretations of ‘you’ there can be. Even though English has lost the distinction between the singular/familiar and plural/polite forms of the second person to be found in many other European languages, we still manage some diversity in its application, at least in fiction. Hovering between the more familiar first and third person narration, and borrowing bits from both, the second person pulls the reader closer to the story, pushing the identification with the narrator and/or creating the illusion of being addressed directly from the page. Either way, the fictional events portrayed can seem more real.  The first person plural point of view is relatively uncommon in fiction, so hurrah for Chuffed Buff Books for inviting submissions with a group narrator for their latest short story anthology. But does it work? Well, as I’m one of the five ‘bits of we’ in the collection I must think so, but not everyone may agree. I wrote A House for the Wazungu from the perspective of the inhabitants of a close-knit community asked to host visitors from abroad. Although a couple of villagers are identified by name – the schoolmaster, Albert Lumumba, and Miriam Moto, the owner of the chai stall – I wanted to conjure a place where individual identities are subsumed within the collective, a culture that values interdependence, as in rural communities of the Global South. The inhabitants of my fictional Kanini would be too busy surviving to concern themselves with such indulgences as communing with their true selves. A novel written exclusively in the first person plural is The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides. Here the narrators are a group of men who, as teenagers, were obsessed with the Lisbon sisters, all of whom committed suicide. Although several of the boys are mentioned by name, it’s never clear who is speaking, so that the narrative unfolds as if chanted by a Greek chorus. Given that adolescents, despite the undoubted self-obsession, are strongly under the sway of peer-group norms, this is the ideal form for this particular novel. Similarly, I used the first person plural in my short story, Kinky Norm, about a bunch of teenage girls rounding on a teacher. Although it starts with an adult ‘I’ looking back on her childhood, she soon takes refuge in the group ‘we’ where no individual is responsible for what occurs: We didn’t sit down together and discuss what we were going to do. There was no plan. No ringleader. It just happened: one of those spontaneous eruptions of adolescent exuberance that our schoolmaster had dedicated his career to nurturing.  Reviewing my latest interview with a debut novelist, I’m wondering how come I keep selecting novels where the protagonist goes hungry. Is this about my drive to connect writing with my garden produce, or the authors’ own obsession with food? As I tuck in five-year-old Pea alongside twelve-year-old Haoua, I’m hoping the grown-up protagonists of the other novels, like the anxious but hands-off adults in The Night Rainbow, will offer her something to eat. Yet, somehow, I don't think Futh will notice that Pea’s mother’s forgotten to feed her, and I’m really not sure how patient Grace would be with small children, but perhaps Satish could get his mother to rustle up some party food. I’ve read some of Pea’s interesting thoughts on food, but does she like chakli? I suppose he’d be willing to try anything, as long as Margot goes first. Nutrition isn’t only a biological necessity; in life, as in novels, food symbolises care, and so fiddling around with it serves to make life harder for the protagonists. Writers sacrifice the desires of their characters in favour of the reader’s love of narrative tension. On one level, the thwarting of even imaginary people seems harsh, yet one of the things that struck me across the five Q&A’s I’ve completed so far was the authors’ empathy for their creations. Claire King told me she loved the way I could make myself feel emotions with fiction I had written myself and, over on The Literary Sofa, she highlighted one consequence of writing from a child’s point of view as the need for plenty of tissues. Shelley Harris was so wrapped up in her character’s psyche that she chose

his career unconsciously, as he would have done himself. The impetus for Gavin Weston’s novel was his concern about the fate of a girl his family had sponsored; its completion has driven him to take a more active role in relation to the practice of child marriage by becoming an ambassador for FORWARD. While we might expect writers to empathise with their child characters and/or those who have been treated unjustly, their empathy for their more prickly protagonists was also apparent:  A good actor reveals a great deal about the character they are portraying even before they open their mouths to speak. It's not just down to clothes and make-up, but how they inhabit their bodies, how and how much they move. A writer faces a similar challenge in embodying her characters but, being cerebral creatures, we might pay more attention to imagining ourselves into another mind living through another situation than writing from the appropriate physical perspective. In the wonderfully wacky film, Being John Malkovich, a puppeteer discovers a portal into the actor’s head. While I’d hesitate to imply I understand what such a complex story is about, the motivation for returning to the portal seems as much about controlling another’s mind as his body. Rather like a writer, don’t you think?

For the movie’s female characters, there’s the frisson of gender-bending sex that makes me think of the female writer writing from the male point of view. I don’t know about other female writers, but when I’m a male narrator, unless he's having sex or going to the toilet, I tend to think of the dangly bit between his legs in symbolic, rather than flesh and blood, terms. Yet at some level we need to convey our characters’ gender, age and physique through their bodies as well as their minds, and to experience those bodies from the inside out. Does a fat person occupy a chair differently to a skinny one: the first squeezing into a confined space and the second getting bum-ache if you leave them sitting too long with insufficient padding? Would a short person notice different things to a tall one as they walk down a street because their gaze is at a different level? What difference does it make to have big feet, or small? To piss from a standing position or sitting down? Complicated stuff? It might be easier, in some ways, to create characters with unusual or distorted bodies, than to write from an ordinary body that is not one’s own. But woe betide the writer who lets her attention lapse, even momentarily, and retreats into her own physique. I had great fun writing about Tamsin, a young woman who wakes up on the morning of her wedding to find that her neck has grown as long as her arm. But with every revision of the story I had to check on the physicals, walking about the house with my hand in the air where I reckoned her head would be to ensure I hadn’t fudged the mechanics. How is your own writerly kinaesthesia and do you have examples of convincing and unconvincing literary bodies to share? I'm watching the evening news and somebody's been killed in a car crash. Let that be a lesson to us all to drive more carefully, I think. A life cut short: a tragedy for his family and friends. Then they bring on a representative of said family and friends to spell it out for me, to mumble through the cliches of loss just in case I haven't got the message. Hey, I want to tell the programme editor, I'm a grown up. I've been to that place where you can't understand how the world keeps turning without that person in it but, even if I hadn't, I think I'd understand that if you lose a loved one you feel sad. My heart hardens for every talking head that tells me how wonderful the deceased was. I think of all the senseless deaths from war and poverty and corruption that don't make it onto my TV. Don't try to dictate what I should feel! I get a similar reaction reading some fiction, where the required emotion seems to be shouting at me in capital letters, bold type and underlined three times. I don't think I'm lacking in compassion – in fact, I'm quite easily moved to tears – but it's been known for an overdone death scene in more than one bestselling novel to have me in fits of laughter. there’s the story which isn’t actually saying anything terribly subtle or interesting about death and what it does to those left behind. I’ve read lots of stories which amount to saying, "Death makes people sad" Emma Darwin A good novel should take us on an emotional journey but, frankly, if the writer lacks the wherewithal to carry the reader with her, perhaps she shouldn't leave the house at all. Or perhaps a leisurely stroll to the coffee shop is the right journey for some if a round-the-world tour entails lost luggage and a night in a prison cell. A lot of people can appreciate a really good cup of coffee: it doesn't have to be the big drama every time. What do I think does make for an emotionally satisfying read?  One option is to tell the story from the point of view of a naive narrator: because she's never experienced a different kind of life, Cathy doesn't recognise the tragedy of her predicament, freeing the up the reader to feel the full impact on her behalf ...  … or from the perspective of a baffled child who inevitably won't have access to the whole picture, but the adult reader will feel the full poignancy of the impact of the tragedy on both him and his parents.  And always always understatement: trusting the reader to know enough about the workings of the world to understand that there's something seriously wrong when it doesn't occur to a child to tell her father that her boots are pinching her toes and she needs new ones. (I know, not the main scene of the novel, but nevertheless a beautiful depiction of child neglect.)  Or keeping us hoping for a favourable outcome against the odds – whoever heard of a hostage situation where they all lived happily ever after? – as if the reader were living it with them day by day. I've read this a couple of times and I still don't know how she does it, but I feel like King Canute trying to hold back the tide.  Again on endings, how about the shock emotional punch? We knew from the start that Kevin had killed several of his schoolmates, but I was in tears when I discovered that that was only the half of what he'd done. Then another thing that makes this book so powerful is the complexity of Eva's reaction. She's as far removed from the grieving relatives on my TV news as you can get. Having struggled to love her son since before he was born, we might expect her to be glad of an excuse to give up on him, but it seems that it's only once the world confirms that he's evil that their relationship can really begin.  Much as we might wish, in real life as in novels, bad things only happened to bad people, we're less likely to feel manipulated as a reader if we find a less sympathetic character tugging at our heartstrings. So Eva Khatchadourian, so David Lurie: they feel like real people, rather than symbols for a particular emotion, stumbling through life in a not particularly admirable way. They're also caught up in something much bigger than themselves, so that what we feel is not just for them as individuals, but for the whole situation, in Lurie's case the pain of a country picking up the pieces after the damage wrought by apartheid. Of course, this is nothing like the whole story. There's much more could be said about each of these novels as well as about the markers of emotional depth. And not just a little anxiety in setting such a high standard in relation to my own work. (I can only fail, and each time fail better.) But an important theme, I think, and one to keep coming back to.

What do you think?  The work and pensions secretary, Iain Duncan Smith, claims he can live like common people on benefits of £53 a week, 15% of median earnings, apparently. Well, obviously that's a red rag to a journalist who will find very good copy in showing it just can't be done (Lucy Mangan) and would prove nothing if it could (Zoe Williams: what's one week of discomfort in the midst of fifty-two in relative luxury?). Might also have been a red rag to this blogger, given that I live in the computer, walk everywhere and my favourite food is lentils. I thought I might manage it if I pretended I wanted to do the 5:2 diet and the last two days were fast days, until I remembered that I wouldn't be able to use the computer I bought back in January because, at a cost of 13 weeks' benefits, I couldn't have afforded it. More disturbing, however, than these glib comments that suggest our politicians have a limited understanding of living on the breadline, is the continual drip feed of misinformation about the poor that comes from official channels. The DWP could soon start running masterclasses in point of view and the unreliable narrator. Perhaps that would be a healthier way of managing the debt than demonising a group of people who are already down: Fraud, which accounts for less than 1% of the overall benefits bill, was

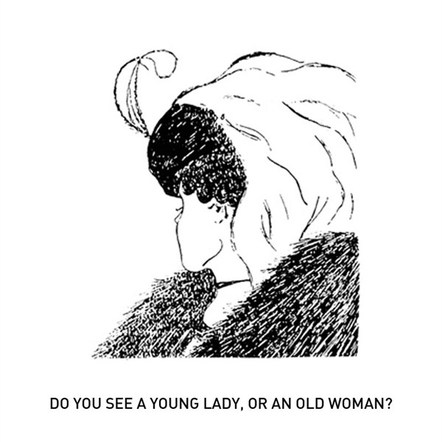

My short story, Reflecting Queenie, has just been published at Creative Writing Ink. It's Snow White from the point of view of the mirror. (Not as dreadful as it sounds, honestly.) As a reader, I've always loved books that bring a fresh perspective to a well-known story. Jane Eyre has never been the same for me since I came across The Wide Sargasso Sea. Looks like others appreciate this kind of novel too.  I like the way the young one's a lady, the old is a woman. I think she used to be a crone when I first met her. I like the way the young one's a lady, the old is a woman. I think she used to be a crone when I first met her. My first taste of the potentially subversive nature of a shift of perspective was with Chaucer at A level. What a revelation! |

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed