Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

|

Two recent reeds that made my 2023 favourites list, tentatively linked by being partly set in countries emerging from oppressive political regimes. The first was more straightforward than the second, but both made me think.

2 Comments

Here are reviews of two different types of English political novel. The first is contemporary and addresses how political events impact on an ordinary London family. The second is a historical novel that gets right to the heart of one of the most turbulent periods of British history.

When I blog about boundaries, I’m usually berating chaotic fictional therapists. Not today. These three intriguing novels are about the liminal space between plant and human; reality and fantasy; and sanity and scapegoating within the political sphere. My short reviews should help you decide whether to cross the threshold.

Although fire has a significant role in both of these novels, I intended this post’s title metaphorically: along with the pandemic, the climate crisis and the (sometimes related) refugee emergency are the defining themes of the 2020s. If you like to explore our times through fiction, as I do, see if you think you’d enjoy The Forests, a translated cli-fi novel and/or The Bones of Barry Knight, a poignant portrayal of people literally or figuratively estranged from their homes.

Do you remember that song about the sisters, devoted to each other … unless a man should come between them? Here are two versions of the novelisation of that story. In the first, set primarily in the Philippines, the two daughters of a former dissident compete for the affections of a powerful man. In the second, a YA dystopian novel, thirty teenagers who’ve been raised together, and think of each other as sisters, also hope to be chosen a high-status man. In both cases, their position is bleak, but the culture and politics of the society they inhabit render the alternative bleaker still.

We can choose our friends but not our neighbours, unless we happen to own a plot of land with cottages to rent or offer free to selected guests. In which case we should choose carefully: in a crisis, out in the countryside, we might have to rely on our neighbours more than we’d expect. But as renters and guests we might not have a say in the matter, as these two novels highlight. The first is about a woman unsettled by the folk beliefs of her neighbours in rural Scotland; the second about a temporarily covid-free community in upstate New York.

When I selected these books for my first reviews of 2022, I thought all they shared was their UK publication date of January 6th. I was wrong. Both are unconventionally structured novels by and about migrants, from the Indian subcontinent, to rich countries founded on the genocide of their indigenous populations, where truth is sometimes sacrificed on the altar of populist politics and the realities of racism and the climate crisis denied. Read on for the different ways these authors handled their theme.

Forgive the tenuous connection between these recent reads, the first featuring harem women in Egypt at the beginning of the twentieth century and the second a contemporary Italian girl who grows into a woman while imprisoned in a container. While you might shudder at the latter, I urge you to give it a chance, as it’s one of my favourite reads of 2021.

These two recent reads – the first non-fiction rooted in the UK, the second a novel visiting Australia, the USA and Iraq – involving characters and authors delving into recent and historical government injustice against its colonised peoples. Read, and use your vote accordingly – but of course you already do!

These two recent reads evoke the cultural climate immediately before the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. The first is a zany novel about the political demise of a former Stasi agent. The second is a translation from German set around a family dinner table in dread of the tyrannical father’s return.

Humour is a tricky business, especially around serious subjects. Get it right, and you can entertain while inciting rage at injustice. Get it wrong, and you risk becoming the target of rage. So what did I make of these two comic novels? The first set in Blitz-blasted London, the second in contemporary Atlanta, which draws you most and are you able to guess which I’d prefer?

When I studied the psychodynamics of organisations, I was encouraged to pay particular attention to how the system responds to a new arrival. Likewise in fiction, the introduction of an outsider is a useful strategy for delving under the skin of a community, especially one in crisis. In both these recent reads, the outsider is a teenage girl, bereft of family, who is smoothly absorbed into the existing structures and, to a small degree, starts to change them. In the first, a translated novella, set in Austria at the end of the Second World War, she is the main point-of-view character. In the second, a debut novel with a contemporary South African setting, she is one of several somewhat shadowy characters. But both books are more about historical and geographical place than person. See what you think.

Realising I needed a stronger reason for pairing these recent reads than the alliterative letter L, I nevertheless feel shabby to have linked them through the childminder role. Okay, the nanny is the protagonist of the first, although she remains a shadowy figure, but only one of many characters in the second where it’s as a mother, rather than as a parent substitute, that she advances the story. But, as was noted at the Zoom meeting of my book group discussion of Lullaby, nannies are as invisible in literature as they are in life. Rather belatedly, I also see that they’re both about fault-lines: the first metaphorically, the second geologically.

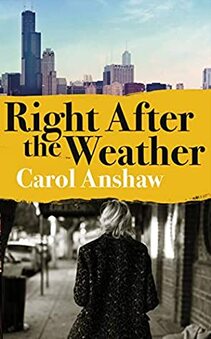

The titles themselves are reason enough to pair these recently published American novels. What I didn’t expect when I picked them from my TBR shelf is that they’d both feature the painful shock, especially among women, of Donald Trump’s election to president. The first zooms in on alienation, perceived inadequacy and a painful discovery of one’s own propensity to violence. The second forefronts the anxiety engendered by the climate crisis and rampant capitalism. I wonder if either of these authors is considering a sequel about their characters’ relationships with the coronavirus pandemic!

|

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed