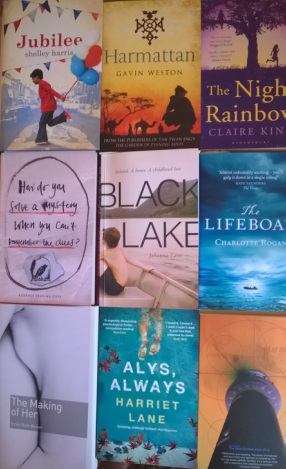

Futh’s narrative in The Lighthouse is interwoven with that of Ester, a somewhat disturbed and scheming woman. We meet another wonderful scheming woman in Frances, the narrator of Alys, Always by Harriet Lane. I connect this novel with Black Lake, not only by the coincidence of the authors sharing the same surname, but in their exploration of the lives of privileged families. In Alys, Always, this is from the outside in, as Frances sets out to inveigle her way into the family of a woman who dies in a car crash. In Black Lake, we are invited to accompany the impoverished “landed gentry” through a period of unwelcome change.

Maud, the elderly narrator of Elizabeth Is Missing by Emma Healey, is also struggling to accommodate to loss. Her confusion over the absence of her good friend, Elizabeth, is compounded by her own memory problems. On top of that, in common with the family in Black Lake, a compulsory house move exacerbates her disorientation.

Maud also presents us with a mystery from the past in terms of an elder sister who went missing during the war. As she approaches the end of her life, the lack of resolution intrudes upon her current functioning. Although much younger, and outwardly at the prime of his life as a successful cardiologist, Satish, in Jubilee by Shelley Harris, is also plagued by uncomfortable memories from his childhood. Like John in Black Lake, he is stalked by a history he is unable to alter and his resulting shame and self-absorption impacts on the whole family.

Like Jubilee and Black Lake, Harmattan by Gavin Weston features the loss of childhood innocence. Although the events of this novel take place in a remote village and in the capital of the Republic of Niger, another link with the Donegal-set Black Lake comes via the Irish family who sponsor twelve-year-old Haoua’s schooling yet are powerless to prevent the damage that ensues.

Claire King’s The Night Rainbow offers another perspective on a difficult period in a young girl’s life. Pea’s family in southern France is as isolated as the Campbell clan in Black Lake. Both these novels contain beautifully lyrical descriptions of the house and surrounding countryside, leading the reader to ponder our attachment to home.

A lifeboat in the middle of the Atlantic offers a vastly different landscape to the European countryside, and Charlotte Rogan does a wonderful job of bringing this to life. As one might guess from the title, water also plays a part in the trials facing the family in Black Lake. Although Grace Winter, the narrator of The Lifeboat, is almost twenty years older, she shares Pea’s instinct for self-preservation and relating her story through the prism of her own particular needs. A whole century later, Marianne in Black Lake is as dependent as Grace on the menfolk for her well-being and survival although, like Ester in The Lighthouse and Frances in Alys, Always, Grace is rather more successful in her manipulations of the opposite sex.

Grace’s torturous journey across the ocean is another link back to our starting point. In The Lighthouse, Futh travels primarily on foot alongside the Rhine, but it’s a ferry across the North Sea that launches him on this path.

So that’s my loop completed, but I’ll leave you with a final connection that was never part of my (conscious) original plan. It turns out I’ve been loyal to the Burial Rites meme after all, albeit in reverse. Like Hannah Kent’s protagonist, Agnes Magnusdottir, Grace Winter in The Lifeboat is facing trial for murder. My copy of Burial Rites even carries an endorsement from Charlotte Rogan on the front.

What’s your verdict on this series of links? If you’ve read any of these novels – or read about them – can you propose any other interconnections? And do, if you have time, browse through my author interviews and associated blog posts for an opportunity to make your own connections with the creators of these super novels.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed