| Pigs will fly before I board a plane again. It’s not that I’m anxious, it’s that - even before the pandemic - long-distance travel no longer felt worth the effort. Diana, the narrator of my debut novel, Sugar and Snails, wasn’t afraid of being airborne either. So why did I send her on a Fear of Flying course? Because, while not averse to flying in a literal sense, she was grounded by inhibition. Fear of intimacy, fear of sex, fear of revealing her true self. When she wouldn’t fly out to Cairo to visit Simon, her friends assumed she was phobic, and clubbed together to pay for her cure. |

Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

|

10 Comments

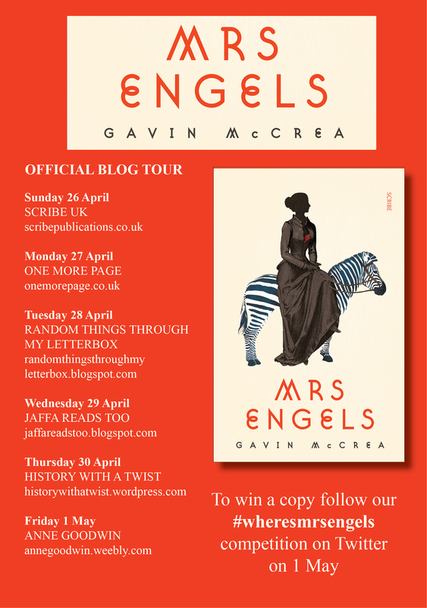

High-powered advertising executive, James Marlowe, is delighted when he wins the brief to create a new campaign for an international bank. But his involvement in the corporate world comes at a heavy cost, as he becomes increasingly dependent on drugs and alcohol in a vain attempt to keep the unethical nature of this endeavour out of mind. This distances him from his beloved wife and son and, eventually, from himself, as a psychotic breakdown lands him in a psychiatric hospital, terrified by a collection of plastic and metal animals and figurines which he calls The Zoo. It’s there that the reader first meets him, and there that we sit alongside him as he gradually pieces together the sequence of events that have brought him to the lowest point of his life. The perspective on corruption is chilling, to quote one of the minor characters, Lou, the moral voice of the novel (p234-5): It’s publication week for Sugar and Snails and I’m breathless with excitement. The buzz is building with two reviews already (from Victoria Best and from Stephanie Burton) and some lovely tweets from early readers at #SugarandSnails. Now, thanks mainly to the generous response to my request for hosts, I’ve made two excursions to other blogs (firstly, to Shiny New Books to share my thoughts on writing about secrets, the false self and insecure identities; secondly to Isabel Costello’s literary sofa to discuss the pleasures of small-press publication), and my case is packed ready to depart on the blog tour proper.

Nancy and Bernadette have spent every summer at the remote farm where their mother grew up. Despite the sullen nature of their uncle, Donn, and the religiosity of their aunt, Agatha, who returned from training to be a nun to keep house for him, it’s an idyllic place to a ten and twelve-year-old from London. But the bond between the sisters is weakening, as Nancy, now at the comprehensive school, wants to play at being a grown-up. And there are far darker forces at work than sibling rivalries. For in Northern Ireland during The Troubles, the English are unwelcome in certain parts and a lonely farm has every chance of being co-opted into the undercover war. Thirty years later, having barely spoken to each other since childhood, the sisters return to the farm with their families on the pretext of seeing the place for one last time before it’s sold. It starts badly: Nancy’s American husband is both overly chatty and bored; Bernie is critical of her sister’s hypervigilance around Nancy’s fourteen-year-old son, who appears to have some kind of attention-deficit disorder (p79):

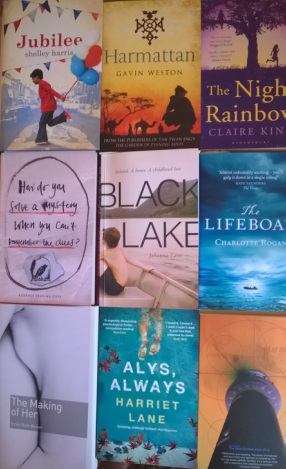

Ah for feck’s sake altogether. Another religious mother. You’d have to ask yourself what’s wrong with this country at all that it can’t stop birthing virtuous ould bags. We know about the darkness of Catholic Ireland here on Annecdotal from our discussion of John Boyne’s dissection of cover-ups in the priesthood in his novel, A History of Loneliness, last year. But interestingly, rampant paedophilia is the one vice Lisa McInerney doesn’t address in her audacious debut novel exploring the murky underbelly of Ireland’s post-crash society. The Glorious Heresies kicks off with a murder in the ground floor apartment of the decommissioned brothel in which the gangster, Jimmy Phelan, has installed his long-lost mother. But this is no police procedural – the reader knows early on whodunnit to whom – but the murder of Robbie O’Donovan is the device through which Lisa McInerney weaves the lives of her misfit characters over the ensuing five years.  Have you ever walked into a room and forgotten what you came for and had to retrace your steps until you know? Have you ever forgotten something you were sure you’d remember and ended up repeating the self-same mistake you’d made the last time? Do you bring back souvenirs from holidays; do you treasure pictures, ornaments and other miscellany, not for their monetary value, but for the memory of how they came your way? Have you ever been touched by music in a place where words hardly signify? Have you ever been affected by a sound so loud you hear it, not just in your ears, but in your entire being? If your answer to any of these questions is yes – and I’d be surprised if it isn’t – you’ll connect with the themes in Anna Smaill’s exceptional debut novel, but you might need to hold onto these ideas to see you through the disorientating opening chapters. The plot is a classic quest: two young men gradually uncover the tangle of lies perpetrated by the elite of their country and set off to infiltrate the seat of power and destroy the source of their destitution, risking their lives in the liberation struggle. It’s a straightforward plot, but deployed with sophistication; there’s no simple demarcation between good and bad. Reaching the hallowed halls, Simon, the narrator wonders (p273): But what did we have to offer her in return, next to this beauty? the voice in my head says. No answers, no order. Nothing but mess, questions, fear.  The daughter of a German concert pianist and her (one-time stand-in page-turner) younger husband, Peggy Hillcoat is eight in the hot summer of 1976 when her father tells her to pack her rucksack and come with him on a journey. As they travel across Europe by car, train and, latterly, on foot, Peggy is less and less confident that this is a holiday. But the stories her father has told her about the secret cabin in the forest spurs her on, and even when she loses her shoe on a perilous river crossing she doesn’t completely give up hope. Yet when they finally reach the cabin, even her father is disappointed at its dilapidated state. Peggy is ready to return home until her father tells her that, not only is her mother dead, but the rest of the world beyond the river is no more. Nine years later, Peggy is back with her mother in London, struggling to adapt to a world of overwhelming luxury and choice (p41):  America at the end of the twenty-first century: a world of droughts; advanced technology; and boys identified with the gene for criminality compulsorily enrolled in corrective institutions from the age of three. James is one such child: a Level 1 student with the prospect of a decent life on graduation in under a year’s time. That’s if he can abide by the school’s strict regulations to avoid accumulating any “demerits” and prevent the memories of a vicious arson attack on his previous school from disturbing his calm. Yet, brutal as the school may be, James is anxious about venturing into the civilian world with its confusing freedoms and potential encounters with the hostile Zeros, religious fundamentalists intent on purifying the world by fire. When, on his first Community Day outing, he steals a girl’s barrette hair slide, a set of progressively harsher punishments is set in train which sees James, not only losing his relatively protected status, but uncovering a network of corruption within the school far deadlier than he could have imagined. The family in the world: The Winter War by Philip Teir and The Lightning Tree by Emily Woof15/1/2015  I’m delighted to bring you reviews of two novels published in the UK today which feature couple and family relationships within a wider sociopolitical context. The Winter War* follows a liberal, middle-class professional Scandinavian couple and their two adult daughters over the course of one winter. While this is a period of change for the family, the pleasure of this novel is less in its plot than in its beautifully drawn characters* and searing sardonic wit*. Max Paul is a Finland-Swede*, a sociologist approaching sixty, living off his reputation as a public intellectual, given an ego-boost when a former student turned journalist requests an interview: One important criteria for all research was that it had to be possible to explain the basic ideas in a simple manner. A good doctoral dissertation could be comprehensively summarised over lunch. Taking this to extremes: a good researcher should, in principle, be able to speak with such enthusiasm that his words could function as a series of pick-up lines. (p74) His wife feels ground down by his emotional neglect and burnt out at work in the human resources department of the Helsinki health service:  What can I say to attract you to a novel that starts and ends with a funeral and mines a deep well of sadness in between? Academy Street is one of the most honest and heart-breaking accounts of fictional grief I’ve come across, as well as one of the most beautifully written. Tess Lohan is marvelling at a blackbird that has flown in through the window to peck at the wallpaper in the family farmhouse as a coffin is carried downstairs. Seven-year-old Tess finds herself intermittently forgetting that her mother has died, that she won’t be able to run and tell her what she’s observed. We stay with Tess over the next six decades as she follows her sister to boarding school, moves to Dublin to train as a nurse and then to New York to spend the bulk of her life on Academy Street until, echoing the opening chapters, she returns to her beloved Easterfield for the funeral of her elder brother. Tess finds moments of intense joy in the little things, but she’s often lonely: her deepest loves are ephemeral, her losses profound*. Like Dear Thief, Academy Street addresses the pain of attachments, whether it is better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all. Stuck in a rut? Love and Fallout by Kathryn Simmonds and a triple flash for not-quite NaNoWriMo2/11/2014  Through most of the 1980s and 1990s a women’s peace camp was held outside the RAF base at Greenham Common to protest against the siting of nuclear missiles there. Thousands of women joined the camp for anything between a single day and several years, making it an important part of recent British sociopolitical history yet, apart from one as-yet-unpublished novel on the theme, Kathryn Simmonds’ debut is the first fictional account of the movement I’ve come across. Tessa is nineteen and fleeing a dead-end job and the humiliation of being dumped by her boyfriend when she packs her rucksack and sets off for Berkshire. Idealistic and naive, only her friendship with the aristocratic beauty, Rori, sustains her through those first few weeks of mud and cold and songs around the campfire, eventually culminating in a spell in prison. Fast forward thirty years and Tessa is the manager of a struggling charity, at loggerheads with her teenage daughter and, along with husband Pete, going through the motions of marital therapy when a friend, Maggie, nominates her to take part in a TV makeover programme. Initially reluctant, she agrees to the filming as publicity for one of her “causes”, but when the producer wants to focus on the “Greenham angle”, the memories from that late adolescent rite of passage come flooding back.  One of the most popular posts on Annecdotal over the last six months was my review of The Good Children by Roopa Farooki. The theme of the novel, which evoked a lively discussion, is the downside of obedience to authority as exposed by Stanley Milgram’s research. In a series of psychological experiments, members of the public showed themselves willing to give painful and damaging electric shocks to another volunteer if asked to do so by an authority figure. This research arose from the attempt to understand the atrocities committed by the Nazis and their collaborators during the Second World War. In her Bailey’s prize shortlisted debut, The Undertaking, Audrey Magee further illuminates this theme through the marriage of Peter Faber, an ordinary German soldier, and an ambitious young woman, Katharina Spinell. The traditional Pakistani arranged marriage which Natasha Ahmed flagged up in the comments on my post seems almost romantic relative to Peter and Katharina’s union, motivated by his desire for leave from the front and hers for the hope of leaving home and a secure pension should her husband die in service. Yet love blossoms against the odds and it’s only the thought of his wife that sustains Peter through the ill-conceived midwinter assault on Stalingrad. She, meanwhile, in conjunction with her acquisitive mother and excessively compliant father, is helping herself to the luxuries left behind in Berlin by the deported Jews.  Blackberry and apple crumble Blackberry and apple crumble While I take great pleasure in my ability to harvest fruit and veg from my garden, I don’t get particularly excited about cooking it. As I couldn’t let it go to waste, I’ve been rustling up some strange concoctions of beetroot, courgettes and beans lately and rushing to put them on the table before it gets too cool to dine in the garden. Cordon Bleu it’s not! I’m hoping my response to Charli Mills’ latest flash fiction prompt won’t also come out as a dog’s dinner. Looking for inspiration for my 99-word food story, I turn to the novels on my physical and virtual bookshelves. Consistent with my miserablist inclinations, there’s a dominant theme of the problems that food or its lack can bring. In Shelley Harris’ novel, Jubilee, a boy’s divided loyalties to his white friends and Asian family is played out in his response to the food his mother plans to cook for a street party in 1970s Britain. (You can click on the link to find the quote.) One of the enduring images in Alison Moore’s debut, The Lighthouse, is the way in which, on a catered walking holiday along the Rhine, the main character consistently fails to get the food he has paid for. Although Lewis, the central character in her second novel, He Wants, is forced to endure fewer physical privations, his food is unsatisfying because it’s not what he actually wants.  even my dahlias are weeping even my dahlias are weeping This weekend’s post from Safia Moore at Top of the Tent, on the motif of loss in Seamus Heaney’s life and poetry, reminded me I’d been meaning to do a post of my own on the theme of grief in fiction and those who create it. While, with reviews of twelve novels I’m hoping to publish this month, I might regret it, the first day of September with autumn creeping upon us seems a good time to revisit my notes and transform them into a proper post. My first post last month was a review of a novel about a family trying to come to terms with the death of a child. Its author, Carys Bray, told me that her own experience of losing a child, albeit in different circumstances, had contributed to her interest in grief and its effects on people. Unresolved grief was the trigger for Janet Watson’s memoir of her adolescence, Nothing Ever Happens in Wentworth. Yet, for many of us, the relationship between grief and loss in our own lives and on the page is less transparent. If fiction thrives on strong emotion and conflict, Carys Bray’s debut novel, about what happens to a Mormon family after their youngest member dies, has all the right ingredients. Grief, while painful to experience, is a powerful launching pad for fiction and, as Derbhile Dromey commented in response to my post on religion and the right to die debate, religion channels conflict in believer and unbeliever alike. Review of A Song For Issy Bradley While four-year-old Issy Bradley is languishing in bed with undiagnosed meningitis, her mother, Claire, is shopping in Asda for affordable party food. Issy’s father, Ian, bishop of the local congregation, is out doing good works for the community and her big sister, Zippy, is lost in Jane Austen’s Persuasion. Of her two brothers, seven-year-old Jacob, is swallowing his disappointment that his dad won’t be able to attend his birthday party and teenager Alma is looking for an escape route so he can go off and play football. When Issy dies, the family’s religious faith proves to be both a source of consolation and pain. The future focus, with the belief that the family will be reunited in eternity, is reassuring for Ian, as he keeps up his church duties, unaware of how much he is neglecting his family and exhausting himself. Claire, who, unlike the other Bradleys, did not grow up as a Mormon but converted when she met Ian, has always found comfort in the sense of order and obedience to a higher power, now feels deserted by God:  Reading Lisa Reiter’s post yesterday on a sanctuary for women on the receiving end of domestic violence, I remembered the research I’d come across years ago indicating that marriage confers greater benefits in health and well-being to men than to women. Alas, I couldn’t access the reference, so this report from the New York Times will have to suffice as my introduction to a trio of debut novels that raise questions about the experience of women in and outside marriage. Two are published in paperback in the UK today and the third came out last year.  North Lees Hall AKA Thornfield in Jane Eyre North Lees Hall AKA Thornfield in Jane Eyre Grand houses loom large in literary fiction, from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre to Alan Hollinghurst’s The Stranger’s Child. There’s a seductive mythology around country houses that seems attractive even to writers with no direct experience of living or working in one. They also, as Blake Morrison points out in an article for The Guardian a few years ago, provide a convenient bridge from book to film. I thought it would be fun to mark the launch day of Johanna Lane’s debut novel, Black Lake, by examining the book from the perspective of the seven factors identified by Morrison as characteristic of the country-house novel. (Note that I’ve amended a couple of the headings to make them more pertinent to this post.)  National identity: Morrison’s article focuses on the English house in a selection of four English novels. But he acknowledges that other countries have an equal or greater claim to the big-house novel: It's arguable that Irish country house literature surpasses ours, because the conflicts it dramatises – both political and religious – are on a larger scale. Black Lake is about one such Irish country house, Dulough in County Donegal. Its history reflects that country’s tragedies: land sold cheaply after the Famine to a Scotsman when Ireland was still part of the British Empire; dispossessed tenants; a questionable involvement with the IRA. In composing a history of his ancestral home, John Campbell moves between pride and shame, fiction and truth, so that he can hardly tell one from the other. If you’ve ever visited this blog before, you may have noticed that I’m rather partial to linking. So when I came across the recent trend for blog posts on six degrees of booky separation on Isabel Costello’s literary sofa, I wondered how I might join in. This month’s starting point is Burial Rites by Hannah Kent, but I thought I’d take myself down a different track involving the titles I’ve featured in my debut novelists Q&A’s. After various deliberations, I’ve ended up with a loop of eight novels, each connected to the one on either side as well as to the one in the middle, for which I’ve selected my most recent addition to my growing list, Johanna Lane’s Black Lake. Some of the links might be rather tenuous, but I’m pleased with how I’ve managed to bring most of them together, my only disappointment being that I couldn’t find a place for Anthea Nicholson’s The Banner of the Passing Clouds (but perhaps that’s for another time). Let me guide you round the circuit and perhaps you’ll find something to inspire your reading or an “x degrees of separation” of your own.  The launch-point is arbitrary, but I’ve chosen The Lighthouse in honour of Alison Moore’s generosity in stepping forward as my first virtual interviewee. The loneliness of the main character, Futh, is somewhat reminiscent of John in Black Lake. Both men struggle to make meaningful emotional connections with their wives, although, as Johanna Lane says in her virtual interview, the outcome for John is more hopeful. Futh’s narrative in The Lighthouse is interwoven with that of Ester, a somewhat disturbed and scheming woman. We meet another wonderful scheming woman in Frances, the narrator of Alys, Always by Harriet Lane. I connect this novel with Black Lake, not only by the coincidence of the authors sharing the same surname, but in their exploration of the lives of privileged families. In Alys, Always, this is from the outside in, as Frances sets out to inveigle her way into the family of a woman who dies in a car crash. In Black Lake, we are invited to accompany the impoverished “landed gentry” through a period of unwelcome change.  Writers learn early to be wary of mirrors. It’s painful to have to score through that purple passage eloquently describing our protagonist’s physical appearance from the top of their head to the tips of their toes. When what we took for writerly innovation is revealed to be a cliché; the first time we allow our narrator to look in the mirror, could be the last. Yet a character who never caught sight of their reflection would be an odd kettle of fish indeed. Plate-glass windows, stainless steel doors: the built environment abounds with reflective surfaces, never mind the mirror above the bathroom sink. Should these be totally out of bounds for writers? Our protagonist’s relationship to mirrors can be useful way of illustrating their character or mood. Are they obsessively drawn to mirrors or avoidant; are they anxiously checking their appearance, or an ordinary woman using lipstick and mascara to compose her outdoor face? Surely it’s the information dump that’s the problem. After all, Elmore Leonard preached against detailed description, not mirrors. A skilfully employed shiny surface can reflect more than is apparent to the eye. For example, in Harriet Lane’s debut novel Alys, Always, Frances sees  So, it's the time of year when the newspapers, half the staff on holiday and the other half nursing hangovers, fob us off with reviews of the year which are nothing more than a rehash of the articles they can most easily lay their hands on, much in the way a cook conjures up a curry from the leftover turkey. Now, I've got more respect for my readers, yet – blame the sherry and figgy pudding, if not the reruns of sentimental Hollywood films – I feel a similar urge to regale you with a look back at my reading and writing and blogging year. I hope you'll find the generosity to indulge me and perhaps return the favour in the comments box below. And, because it's the time of year for tantalising puzzles, there's a connection between the numbers marked with an asterisk. |

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed